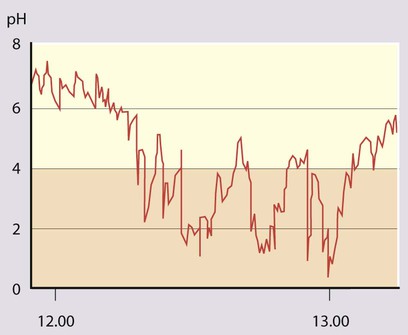

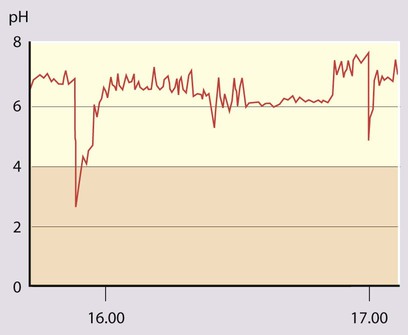

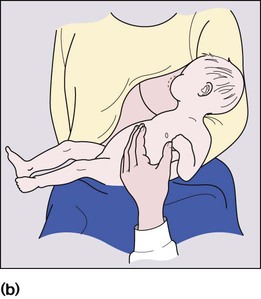

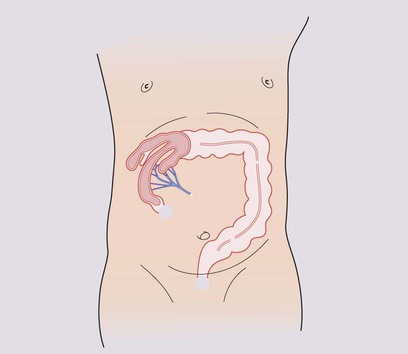

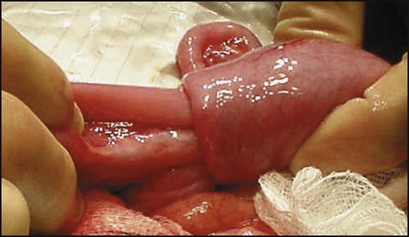

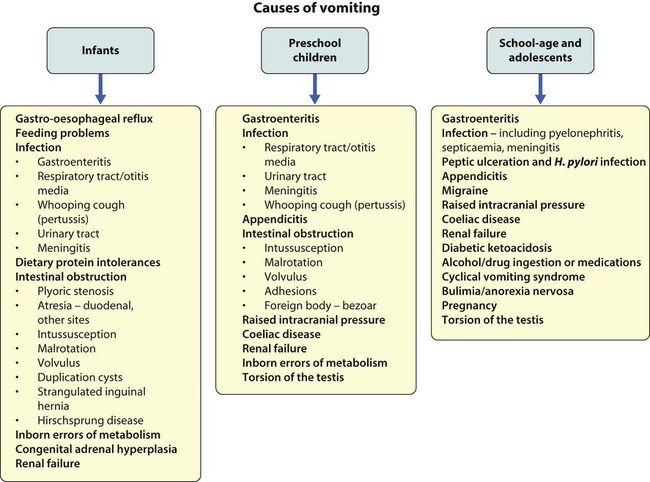

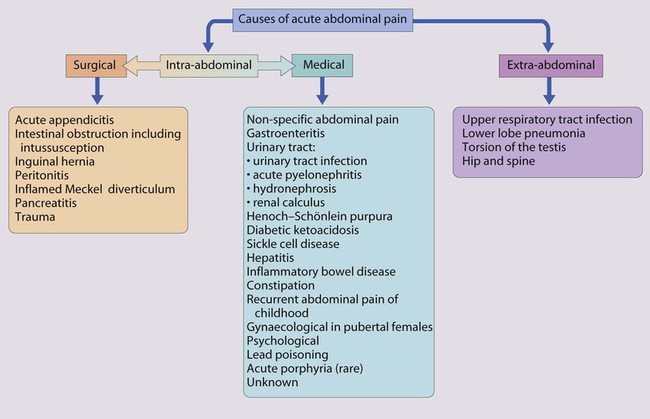

Features of gastrointestinal disorders in children are: • Vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea are common and usually transient; serious causes are uncommon but important to identify • Worldwide, gastroenteritis is responsible for 1.2 million deaths/year, one of the commonest causes of death in children <5 years old • The number of children and adolescents developing inflammatory bowel disease is increasing Vomiting is the forceful ejection of gastric contents. It is a common problem in infancy and childhood (Fig. 13.1 and Box 13.1). It is usually benign and is often caused by feeding disorders or mild gastro-oesophageal reflux or gastroenteritis. Potentially serious disorders need to be excluded if the vomiting is bilious or prolonged, or if the child is systemically unwell or failing to thrive. In infants, vomiting may be associated with infection outside the gastrointestinal tract, especially in the urinary tract and central nervous system. In intestinal obstruction, the more proximal the obstruction, the more prominent the vomiting and the sooner it becomes bile-stained (unless the obstruction is proximal to the ampulla of Vater). Intestinal obstruction is associated with abdominal distension, more marked in distal obstruction. ‘Red Flag’ clinical features suggesting significant organic pathology are listed in Box 13.1. Complications are listed in Box 13.2. Severe reflux is more common in: • children with cerebral palsy or other neurodevelopmental disorders, when energetic management, surgical if necessary, may transform the child’s quality of life • preterm infants, especially if coexistent bronchopulmonary dysplasia • following surgery for oesophageal atresia or diaphragmatic hernia. • 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring to quantify the degree of acid reflux (see Case History 13.1). • 24-hour impedance monitoring. Available in some centres. Weakly acidic or non-acid reflux, which may cause disease, is also measured. • Endoscopy with oesophageal biopsies to identify oesophagitis and exclude other causes of vomiting. • Vomiting, which increases in frequency and forcefulness over time, ultimately becoming projectile • Hunger after vomiting until dehydration leads to loss of interest in feeding Unless immediate fluid resuscitation is required, a test feed is performed. The baby is given a milk feed, which will calm the hungry infant, allowing examination. Gastric peristalsis may be seen as a wave moving from left to right across the abdomen (Fig. 13.3a). The pyloric mass, which feels like an olive, is usually palpable in the right upper quadrant (Fig. 13.3b). If the stomach is overdistended with air, it will need to be emptied by a nasogastric tube to allow palpation. Ultrasound examination is helpful (Fig. 13.3c) if the diagnosis is in doubt. The initial priority is to correct any fluid and electrolyte disturbance with intravenous fluids (0.45% saline and 5% dextrose with potassium supplements). Once hydration and acid–base and electrolytes are normal, definitive treatment by pyloromyotomy can be performed. This involves division of the hypertrophied muscle down to, but not including, the mucosa (Fig. 13.3d). The operation can be performed either as an open procedure via a periumbilical incision or laparoscopically. Postoperatively, the child can usually be fed within 6 h and discharged within 2 days of surgery. Assessment of the child with acute abdominal pain requires considerable skill. The differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in children is extremely wide, encompassing non-specific abdominal pain, surgical causes and medical conditions (Fig. 13.4). In nearly half of the children admitted to hospital, the pain resolves undiagnosed. In young children it is essential not to delay the diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis, as progression to perforation can be rapid. It is easy to belittle the clinical signs of abdominal tenderness in young children. Of the surgical causes, appendicitis is by far the most common. The testes, hernial orifices and hip joints must always be checked. It is noteworthy that: • Lower lobe pneumonia may cause pain referred to the abdomen • Primary peritonitis is seen in patients with ascites from nephrotic syndrome or liver disease • Diabetic ketoacidosis may cause severe abdominal pain • Urinary tract infection, including acute pyelonephritis, is a relatively uncommon cause of acute abdominal pain, but must not be missed. It is important to test a urine sample, in order to identify not only diabetes mellitus but also conditions affecting the liver and urinary tract. Acute appendicitis is the commonest cause of abdominal pain in childhood requiring surgical intervention (Fig. 13.5). Although it may occur at any age, it is very uncommon in children <3 years old. The clinical features of acute uncomplicated appendicitis are: – Vomiting (usually only a few times) – Abdominal pain, initially central and colicky (appendicular midgut colic), but then localising to the right iliac fossa (from localised peritoneal inflammation) • The diagnosis is more difficult, particularly early in the disease • Faecoliths are more common and can be seen on a plain abdominal X-ray • Perforation may be rapid, as the omentum is less well developed and fails to surround the appendix, and the signs are easy to underestimate at this age. Intussusception describes the invagination of proximal bowel into a distal segment. It most commonly involves ileum passing into the caecum through the ileocaecal valve (Fig. 13.6a). Intussusception is the commonest cause of intestinal obstruction in infants after the neonatal period. Although it may occur at any age, the peak age of presentation is between 3 months and 2 years. The most serious complication is stretching and constriction of the mesentery resulting in venous obstruction, causing engorgement and bleeding from the bowel mucosa, fluid loss and subsequently bowel perforation, peritonitis and gut necrosis. Prompt diagnosis, immediate fluid resuscitation and urgent reduction of the intussusception are essential to avoid complications.

Gastroenterology

Vomiting

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Investigation

Pyloric stenosis

Diagnosis

Management

Acute abdominal pain

Acute appendicitis

Intussusception

Gastroenterology