21

Gastroenterology

Chapter map

Intestinal disorders are usually acute and infective. They are most serious in infancy, when fluid and electrolyte balance can become dangerously disturbed within a matter of hours and cause death or brain damage. Assessment of chronic disorders can be difficult. In most children, recurrent abdominal pain, gastro-oesophageal reflux, constipation and persistent diarrhoea are benign and self-limiting. Less common but equally important are intestinal obstruction, and malabsorption states including coeliac disease and cystic fibrosis. In children, ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease are uncommon, while peptic ulcers and neoplasm are rare.

This chapter will first review major gastrointestinal presenting symptoms, and then key pathologies.

21.1.5 Constipation and soiling

21.2.4 Gastrointestinal infections

21.2.6 Food allergy and intolerance

21.2.7 Chronic inflammatory bowel disease

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT21.1 Symptoms

21.1.1 Vomiting

Acute-onset vomiting is a common symptom. It is highly non-specific and commonly not due to gastroenterological disease. Projectile (forceful) vomiting in the first weeks of infancy may mean pyloric stenosis. Consider intestinal obstruction or ileus if vomiting is persistent or bile stained.

Persistent mild symptoms are very common in babies, who bring up small amounts of food when breaking wind after a feed. This is possetting, a normal process, and the baby is happy and gains weight well. Significant vomiting will be accompanied by weight loss, or at least inadequate weight gain.

- Infants: faulty feeding technique (especially overfeeding)

- Older children: dietary indiscretions

- Gastritis (with or without enteritis)

- Parenteral infections (e.g. tonsillitis, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary infection)

- Appendicitis

- Intestinal obstruction, congenital or acquired

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Meningitis, encephalitis

- Space-occupying lesions (tumour, abscess, haematoma)

- Rumination

- Bulimia

- Periodic syndrome (cyclical vomiting – part of migraine spectrum)

- Travel sickness

- Poisoning.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT21.1.1.1 Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Asymptomatic, infrequent reflux of gastric contents is physiological. Reflux is most common in young infants, who effortlessly regurgitate milk over parents, furniture and carpets. The vast majority remain well; reassurance and growth monitoring is all that is justified, and symptoms resolve in infancy with maturation of lower oesophageal sphincter function. Beware if any of the following are present, since they indicate more serious reflux and the need for expert assessment and management: suboptimal weight gain, feeding problems, haematemesis, anaemia and recurrent respiratory symptoms. Reflux is most common and more often severe in infants with cerebral palsy or neurodevelopmental problems, and in preterm infants and young children with chronic respiratory disorders. Investigations include barium studies, 24 h monitoring of oesophageal pH and endoscopy.

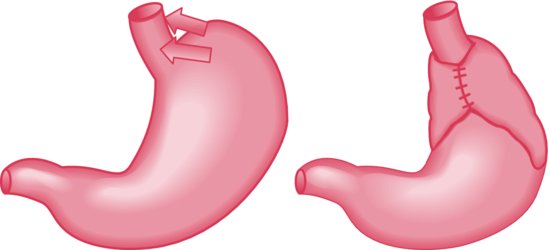

In most infants, parents are reassured, and no treatment is given. Surgical treatment with fundoplication (see Figure 21.1), is rarely needed.

Figure 21.1 Nissen’s fundoplication involves wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the lower oesophagus, so that it is occluded by increased intra-abdominal pressure.

TREATMENT Gastro-oesophageal reflux

TREATMENT Gastro-oesophageal reflux- Reassurance

- Feeding technique – avoid overfeeding, smaller more frequent feeds

- Positioning

- Raise head of cot (brick under each leg)

- Avoid semi-supine position (e.g. in infant seat) after feeds

- Raise head of cot (brick under each leg)

- Milk thickeners

- Antacids

- Gastric acid secretion (H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors)

- Fundoplication (rare).

21.1.1.2 Haematemesis

This is not common. Fresh or altered blood may have been swallowed (e.g. epistaxis, tonsillectomy, cracked nipple in the breast-fed infant). Acute gastritis, oesophagitis (typically with reflux), oesophageal varices and peptic ulcer should be considered. Exclude bleeding diathesis. If recent haematemesis is suspected, check the stools for occult blood.

21.1.2 Abdominal pain

21.1.2.1 Acute abdominal pain

| Condition | Site of pain and tenderness |

| Non-organic pain | Central |

| URTI/tonsillitis | Central/RIF |

| Pyelonephritis | Loins |

| Lower lobe pneumonia | Upper abdomen |

| Constipation | Lower abdomen |

| Mesenteric adenitis | Lower abdomen, often RIF |

This important symptom is highly non-specific. Acute central abdominal pain and vomiting are, for example, common symptoms of tonsillitis. In infants, abdominal pain may be inferred from spasms of crying, restlessness and drawing up the knees. Children can indicate the site of a pain from about the age of 2 years. If there is generalized illness, vomiting, bowel disturbance or fever, assess carefully and re-examine after a few hours. Intussusception, complicated hernia and appendicitis are amongst the important surgical causes. Acute abdominal pain is a typical presenting feature in diabetic ketoacidosis (Section 27.1), Henoch–Schönlein syndrome (Section 23.3.5) and sickle cell disease (Section 25.2.2.3).

Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis occurs at all ages but is uncommon under the age of 2 years. The classical history of central abdominal pain, moving to the right iliac fossa, aggravated by movement and associated with fever and acute phase response, raises suspicion, which may be confirmed by the finding of localized tenderness in the right iliac fossa. Unfortunately, it is not always that easy.

Diagnostic difficulties may be caused by an appendix in an unusual position. Diagnosis of appendicitis is particularly difficult in younger children. The doctor who diagnoses appendicitis before perforation in a 2-year-old deserves praise. Consider imaging (ultrasound/CT) in difficult cases.

21.1.2.2 Chronic abdominal pain

PRACTICE POINT

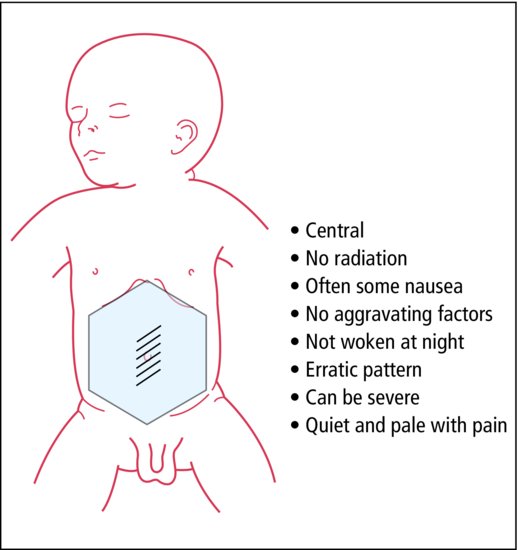

PRACTICE POINTRecurrent abdominal pain is common throughout childhood and usually of no serious significance when the child is otherwise healthy (Figure 21.2). History, examination, growth assessment and urine microscopy and culture are always justified. The idea that one should exclude all organic causes is naive and usually not possible. Constipation is a common cause and is usually, but not always, apparent on history and examination.

In some children, recurrent abdominal pain betrays emotional disorders. It has often persisted for a year or more by the time medical advice is sought. The child may complain of pain several times in a week and then not at all for a month or two. As children with recurrent abdominal pain are usually of school age, the parents often suspect some stress at school. In many there is a family history of irritable bowel syndrome or migraine, and the childhood equivalent of irritable bowel syndrome is increasingly well recognized. Irritable bowel syndrome, non-ulcer dyspepsia and abdominal migraine may be helped by specific treatments for these conditions.

- Not central

- Wakes at night

- Related to food

- Vomiting/diarrhoea

- Generalized illness

- Dysuria, daytime enuresis

21.1.3 Abdominal distension

Abdominal distension can be difficult to assess because of the great, normal variation. Fat babies appear to have bigger tummies than thin, muscular babies. Toddlers are normally rather pot-bellied in comparison with older children. Causes include fat, faeces, flatus and fluid: do not forget to test for ascites (Section 3.5.5, p. 36).

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT21.1.4 Diarrhoea

Diarrhoea or constipation requires detailed enquiry. The number and consistency of stools passed by children, especially infants, is very variable. Breast-fed babies pass loose, bright yellow, odourless stools, between seven times a day and once every 7 days. Bottle-fed babies pass paler, firmer stools which may cause straining during defaecation. Unless this straining causes pain or rectal bleeding, it should not be called constipation. Chronic or severe constipation may lead to abdominal pain, abdominal distension, rectal bleeding and feeding problems, and may be associated with emotional and behaviour disorders (Section 11.5.2.1, p. 104).

- In infants, too much, too little or the wrong kind

- In older children, dietary indiscretion

- Bacterial or viral infection

- Postenteritic syndrome

- Ulcerative colitis/Crohn disease

- Giardiasis

- Parenteral infections

- Steatorrhoea (e.g. coeliac disease, cystic fibrosis)

- Disaccharide intolerance

Many toddlers and some older children continue to have three or four bowel actions a day, after meals. ‘Toddler diarrhoea’ describes the occurrence of frequent loose stools at this age without any pathology, and is due to a rapid bowel transit time. Undigested food is seen in the stool within a few hours of being eaten (our personal best was carrots at 20 min).

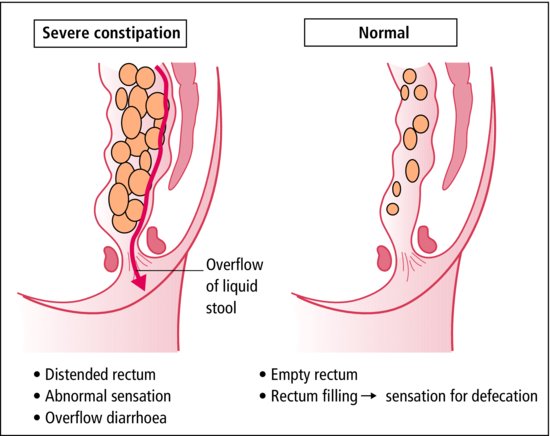

Chronic constipation in infants or children may lead to faecal impaction and overflow soiling. This may be mistaken for diarrhoea.

21.1.4.1 Dehydration

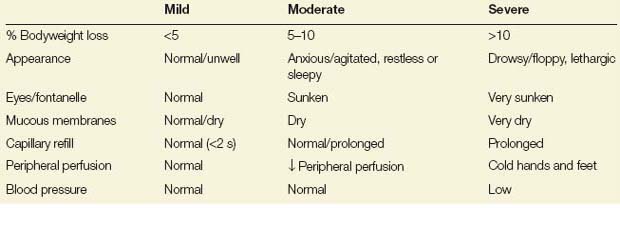

Early recognition of shock (suboptimal peripheral perfusion) and hypovolaemia is very important in the acute illness. No one sign diagnoses dehydration (Table 21.1).

Table 21.1 Dehydration

Urine output is reduced as dehydration becomes more severe. Children are very efficient at maintaining central blood pressure in the face of hypovolaemia. Hypotension is a late sign, and BP is normal in most children with shock.

In every acutely ill child, check for hypovolaemic shock: the pale, mottled, floppy infant with cold sweaty hands and feet is in shock. Emergency treatment is needed to restore circulation.

21.1.5 Constipation and soiling

This is most common at 5–10 years. Often there is no obvious trigger, or there has been minor change in diet or bowel habit (for example with illness or travel). Constipation leads to faecal retention (Figure 21.3). Hard stool causes pain or anal fissure which inhibits defaecation and increases constipation. At other times, poor toilet training has resulted in infrequent and incomplete bowel actions. The rectum becomes distended with impacted faeces. In extreme cases, only liquid matter can escape, causing overflow diarrhoea with faecal soiling. The child is often unaware of this. His school companions, in contrast, are only too well aware of it, and the child with soiling may become a social outcast.

The abdomen contains hard, faecal masses, often filling the lower half of the abdomen. There is unlikely to be confusion with the rare Hirschsprung disease (see Section 21.2.2.1, p. 211), which usually presents at a much earlier age with failure to thrive.

TREATMENT Management of constipation

TREATMENT Management of constipation- Increased dietary fibre (e.g. bran)

- Ideally the whole family should adopt a high-fibre diet

- Increased fluid and exercise

- Instant success is not to be expected – rectum takes time to resume its normal calibre and sensation.

- Regular toileting (1–2 times daily, 20 minutes after meal – to benefit from the gastrocolic reflex)

- Can combine with star chart)

- Consider disimpaction – thorough emptying of accumulated faeces with laxatives (rarely enemas)

- Faecal softening agents (e.g. Macrogols – polyethylene glycol 3350 with electrolytes; lactulose)

- Stimulant laxative may be added later

- May be needed for many months.

RESOURCE

RESOURCEEncopresis (deliberate deposition of stool in inappropriate places) is a symptom of serious psychological upset, and the advice of a child psychiatrist should be sought.

21.1.6 Rectal bleeding

Blood in the stools is an alarming symptom, although the cause is often trivial. The most common cause is anal fissure. Bleeding from the duodenum or above will usually cause melaena, although copious bleeding (e.g. swallowed blood after epistaxis or tonsillectomy) may cause red blood to appear with the stool. Blood from the ileum or colon is freely mixed with faecal matter; that from the rectum or anus is only on the surface of the stool. Examination of the perineum, anus and rectal examination (Section 3.5.5, p. 36) may reveal the site of bleeding, or confirm the presence of blood in the stool (Table 21.2).

Table 21.2 Causes of bleeding per rectum

| Site | Condition | Clinical picture |

| Ileum | Intussusception | Colicky pain; redcurrant jelly stool; palpable mass |

| Meckel’s diverticulum | Intermittent abdominal pain and bleeding (red or melaena) | |

| Colon | Dysentery (Shigella, Salmonella) | Acute mucoid diarrhoea and pain |

| Ulcerative colitis | Chronic mucoid diarrhoea and pain | |

| Crohn’s disease | Abdominal pain, diarrhoea and growth failure | |

| Intussusception | As above | |

| Rectum | Polyp | Recurrent bleeding: no pain |

| Prolapse | Prolapse visible | |

| Anus | Fissure/constipation | On defaecation, much pain and little blood |

| Sexual abuse | Dilated/sore anus |

Piles and rectal carcinoma are very rare in children, and children with more than one episode without known cause should be seen in hospital. Colonoscopy is helpful. Meckel’s diverticulum is an embryological remnant of the vitelline duct on the ileum and is present in 2% of the population, although in most it causes no symptoms. It often contains gastric mucosa which may ulcerate and bleed, causing rectal bleeding and anaemia. Radioactive technetium is selectively taken up by gastric mucosa and this provides the basis for an elegant diagnostic test.

21.2 Pathologies

21.2.1 The mouth

21.2.1.1 The teeth

There is considerable normal variation in the time of eruption of teeth, which may lead to unnecessary worry (Section 3.3). Preventative dental health is important for all children. Frequent sugary food should be avoided; we should not forget iatrogenic problems with medicines or vitamin drops. The bottle to suck while falling asleep or the dummy soaked in sweet fluid should be banned. Severe dental problems are more common in children with neurodevelopmental problems and in association with acid reflux.

Include the teeth in the examination of the mouth. It gives an opportunity for congratulation or health education.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree