Chapter 61 Gastroenterology

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

ETIOLOGY

What Causes Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding?

Blood in the stool or vomitus is typically of great concern to parents and physicians. Massive bleeding can be life threatening and must be treated rapidly to replenish the vascular compartment and stop the hemorrhage. In many other cases the quantity of blood lost is not so large as to be immediately dangerous. Table 61-1 lists the common causes of bleeding by age. Congenital lesions cause problems early in life, but some types of bleeding can occur at any age.

Table 61-1 Causes of Gastrointestinal Bleeding by Age

| Age | Hematemesis* | Rectal Bleeding |

|---|---|---|

| Neonatal period (birth-6 weeks) | Ingested maternal blood—first days of life | Anal fissure |

| Peptic disease | Allergic colitis | |

| Coagulopathy | NEC | |

| Arteriovenous malformation | Hirschsprung’s disease | |

| Duplication cyst | Volvulus | |

| Infancy to 2 years | Peptic disease | Allergic colitis |

| Varices | Intussusception | |

| Foreign body | Meckel’s diverticulum | |

| NSAIDs | Bacterial colitis | |

| Arteriovenous malformation | ||

| Coagulopathy | ||

| Children older than 2 years | Peptic disease | Juvenile polyp |

| Esophageal varices | Meckel’s diverticulum | |

| Mallory-Weiss tear | Bacterial colitis | |

| NSAIDs | Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia | |

| Foreign body | HSP, HUS | |

| Arteriovenous malformation | IBD | |

| Coagulopathy | ||

| Any age | Peptic disease | Bacterial/amebic dysentery |

| Arteriovenous malformation |

HSP, Henoch-Schönlein purpura; HUS, hemolytic uremic syndrome; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

* Any cause of hematemesis can also present as rectal bleeding.

EVALUATION

What Questions Help Assess GI Bleeding?

Is it blood? Foods with intense red coloring such as candy, soft drinks, and beets can produce red-colored stool. If a parent shows you a cherry-red diaper, you should consider that the color may be from something other than blood. A simple test for occult blood should be performed.

How much blood has been lost? Ask how much blood has been seen. Streaks of blood on the surface of a hard stool, bloody mucus mixed in stool, teaspoon-sized clots, or a larger amount of bloody material? If the child passed blood into the toilet, ask about the color of the water in the toilet bowl: Light pink is of less concern than opaque red. You must also consider that there may be a larger quantity of blood in the intestinal lumen that has not yet shown itself. Evaluating the child for signs of shock, tachycardia, and systolic hypotension is therefore critical.

Where is the bleeding coming from? Not all blood in the toilet, diaper, or vomitus comes from the digestive system. Your history and examination must seek evidence of bleeding from surrounding structures. Vomited blood may have originated in the lungs, mouth, or nasopharynx. Blood coming from below may have a vaginal or urinary tract source. When no other source seems likely, think about where in the gut the bleeding may be coming from. Vomited blood is nearly always from the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum. Rectal bleeding may come from anywhere within the gut. Melena (black, sticky, tarry, sickly sweet–smelling stools) typically indicates a very high source of bleeding, whereas bright red blood suggests very distal bleeding. Dark red blood mixed with stool suggests bleeding higher in the colon. When blood is only on the surface of the stool, a much more distal source is likely. With large volumes of rectal bleeding, the degree of redness becomes less reliable, because of rapid transit of the blood through the gut. In this case, passing a nasogastric tube to sample gastric contents helps rule out a proximal source.

What is the cause of the hemorrhage? To answer to this question you must have information about the symptoms that preceded and accompanied bleeding, the age of the patient, the medical history, the medication history, and the amount and source of bleeding. Refer to Table 61-1 for causes of bleeding by age and Table 61-2 for causes of bleeding by clinical presentation.

Table 61-2 Causes of Gastrointestinal Bleeding by Clinical Presentation

| Presentation | Suspected Condition | Imaging Test(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Bowel obstruction symptoms (colicky pain, vomiting) accompanying bleeding | Volvulus | Flat and upright plain films of abdomen |

| Intussusception | Abdominal ultrasonogram | |

| Upper GI series (volvulus) | ||

| Barium enema (intussusception) | ||

| Epigastric pain, hematemesis | Peptic ulcer | Upper GI series (low sensitivity, endoscopy preferred) |

| Massive, painless hematemesis | Esophageal varices | None. Upper endoscopy indicated to diagnose and treat bleeding |

| Peptic ulcer | ||

| Massive, painless rectal bleeding | Meckel’s diverticulum | Meckel’s scan |

| AV malformation | Arteriogram, labeled RBC scan | |

| Bloody diarrhea | Inflammatory bowel disease | Barium enema (colonoscopy preferred) |

| Formed stool with streaks of blood | Allergic colitis (infant) | None. Consider sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy instead |

| Rectal fissure | ||

| Juvenile polyps |

AV, Arteriovenous; GI, gastrointestinal; RBC, red blood cell.

What Should I Look for on Physical Examination?

First, remember the ABCs (Chapter 31): Determine the hemodynamic status. Is the child pink, blue, or pale? Is there increased work of breathing? Are blood pressure and pulse rate appropriate for age, high, or low? Are pulses palpable and strong? Is capillary refill < 2 seconds or prolonged? Look for bruising and petechiae, which indicate possible coagulopathy. Signs of liver disease include hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, and prominent abdominal veins. Evaluate the abdomen carefully for tenderness, distention, bowel sounds, and mass lesions. Location of tenderness may help identify the source of bleeding. For example, epigastric tenderness suggests peptic disease, whereas a tender mass in the right lower quadrant may indicate Crohn’s disease. Bowel obstruction such as volvulus or intussusception causes hyperactive, high-pitched “pinging” bowel sounds; distention; bilious emesis; and colicky pain. Always perform a rectal examination and test stool for blood, regardless of stool color.

What Laboratory Tests Should I Perform?

Table 61-3 lists suggested laboratory studies for children with GI bleeding. Remember that acute bleeding will not immediately cause a drop in the hemoglobin or hematocrit. You must select tests to rule out coagulopathy, identify liver disease, and assess hydration status, renal function, and electrolytes. When there is evidence of massive bleeding, send a specimen to the blood bank immediately!

Table 61-3 Laboratory Investigation of Gastrointestinal Bleeding

| CBC with WBC differential, platelet count |

| PT, PTT |

| AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, GGT |

| Electrolytes, BUN, creatinine |

| Stool for WBC, culture (bloody diarrhea) |

| Type and crossmatch |

| Hemoccult or similar test for suspected blood in stool and vomitus |

ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; WBC, white blood cell.

What Imaging Studies Should I Order?

Your clinical judgment is important at this point. Do not order every test available—focus on those studies that will best test your diagnostic hypothesis. In many cases, endoscopy is preferred to any other test. Table 61-2 lists imaging studies for the evaluation of different clinical presentations.

TREATMENT

How Should I Begin Management of Gastrointestinal Bleeding?

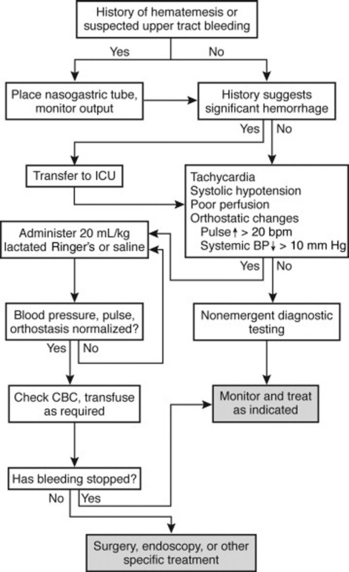

Your initial evaluation determines possible sources of bleeding and the patient’s hemodynamic status. If the child has normal vital signs and a history of only minor blood loss, such as a few streaks of bright red blood in the stool, proceed directly to appropriate diagnostic tests. If bleeding is more severe, you must stabilize the patient and stop the bleeding. Figure 61-1 gives a suggested approach to management.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

ETIOLOGY

What Is Inflammatory Bowel Disease?

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to disorders that cause chronic inflammation of the GI tract. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is characterized by continuous, chronic mucosal inflammation only in the colon, starting from the anus and extending proximally to a variable extent. Crohn’s disease (CD), on the other hand, is a chronic inflammatory disorder that may involve any part of the GI tract, from the mouth to the anus. UC and CD usually can be differentiated by the clinical features listed in Table 61-4.

Table 61-4 Differentiating Features of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution | Colon only | Any part of gastrointestinal tract |

| Involvement | Mucosal only Continuous | Transmural Discontinuous (“skip areas”) |

| Clinical features | ||

| Rectal bleeding | Usual | Sometimes |

| Abdominal mass | Absent | Sometimes |

| Perianal disease | Absent | Sometimes |

| Histology | ||

| Intestinal fistulas | Absent | Sometimes |

| Granuloma | Absent | Sometimes |

What Is the Differential Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease?

Because IBD has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, the differential diagnosis can be quite wide. Bacterial infections and parasitic infestations can mimic UC and Crohn’s colitis. Chronicity of symptoms and negative stool culture results favor IBD as opposed to infection. Abdominal pain has a very broad list of potential causes (see Chapter 17). Celiac disease can present with growth failure, anemia, abdominal pain, and nonbloody diarrhea.

EVALUATION

How Does Inflammatory Bowel Disease Typically Present?

IBD, particularly CD, has a wide variety of presentations, including extraintestinal manifestations (Table 61-5). These features may appear before, with, or after the onset of the GI symptoms. Growth failure is a prominent extraintestinal manifestation of CD.

Ulcerative colitis: Children with UC have frequent loose, watery stools that contain blood and mucus. They also have colicky abdominal pain, urgency, tenesmus (sensation of incomplete emptying), and often wake up at night for bowel movements.

Crohn’s disease: The clinical presentation of CD varies, depending on the involved region of the GI tract. The ileocecal region is the most common site affected, and patients typically have crampy abdominal pain and diarrhea, with or without visible blood. Patients with extensive CD in the colon have symptoms similar to UC. CD localized to the small bowel is often relatively silent, except when inflammation and scarring lead to obstructive symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and distention. More commonly, these children have poor weight gain, decreased energy, and anemia. Adolescents with CD may have delayed puberty. Patients with gastric or duodenal involvement complain of epigastric pain and vomiting.

Table 61-5 Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

| Site | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Extremities | Arthralgia, arthritis, clubbing |

| Skin | Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum |

| Liver | Sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis |

| Eye | Uveitis, episcleritis |

| Bone | Osteopenia |

| Renal | Urolithiasis, enterovesical fistulas |

| General | Fever, growth failure, pubertal delay |

What Should I Look for on Physical Examination?

Vital signs and hydration status should be assessed. Assessment of growth is essential: Children with small bowel CD often appear chronically ill because of growth failure, malnutrition, and anemia. Also assess the sexual maturity of adolescents. Look for abdominal tenderness, guarding, and masses. In most cases of CD and UC, abdominal tenderness is minimal, but a tender right lower quadrant mass resulting from inflamed, thickened bowel may be found in CD. Severe abdominal tenderness with distention and guarding is an ominous sign indicating toxic megacolon or bowel perforation. The presence of oral ulcers or perianal skin tags, abscesses, or fistulas are typical of CD. Do not forget to look for the extraintestinal manifestations listed in Table 61-5.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree