20.4 Gastro-oesophageal reflux and Helicobacter pylori infection

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Pathophysiology (Box 20.4.1)

Box 20.4.1 Pathophysiological mechanisms of gastro-oesophageal reflux in infants, children and adolescents

LOS, lower oesophageal sphincter.

Modified from Davidson GP, Omari TI 2001 Pathophysiological mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 3:257–262.

Clinical manifestations

There are many causes of regurgitation and vomiting in infants and children, both within the gastrointestinal tract and external to it. The more common causes are outlined in Box 20.4.2.

Table 20.4.1 highlights the symptoms suggestive of GORD in infants and children. Symptoms do vary according to age. Infants more frequently regurgitate but have also been shown to have reflux-related neurobehavioural symptoms including irritability, crying, fussiness and back-arching but not gagging. More serious complications include apnoea, acute life-threatening events and recurrent chest disease secondary to aspiration. Chronic cough without associated lung disease is unlikely to be reflux-related.

Table 20.4.1 Symptoms suggestive of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in infants and children

| Infants | Children | |

|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Feeding difficulties | Waterbrash |

| Failure to thrive | Nausea | |

| Malnutrition | Dysphagia | |

| Cow’s milk protein intolerance | ||

| Respiratory | Cough, stridor | Chronic cough |

| Cyanotic episodes | ||

| Apnoea | ||

| Acute life-threatening events | ||

| Acid reflux | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Apnoea, cyanotic episodes | Heartburn |

| Colic, irritability | Oesophageal obstruction | |

| Sleep disturbance | Dysphagia, odynophagia | |

| Flexion patterns after feeds | Night waking | |

| Hiccoughs | Haematemesis | |

| Iron deficiency | ||

| Respiratory | Apnoea, cyanotic episodes | |

| Stridor | ||

| Neurobehavioural | Sandifer syndrome | |

| Seizure-like events (similar to infantile spasms) |

There are many potential extra-oesophageal manifestations of GORD; these are highlighted in Table 20.4.2 and need to be considered as they may be the only presenting symptom or sign. Ear nose and throat manifestations such as otitis media, sinusitis and dental erosions are now being recognized. Although a link between many extra-oesophageal manifestations and GORD has been identified, causality has not been proven, and data supporting improvement in symptoms with GORD treatment are sparse.

Table 20.4.2 Potential extra-intestinal manifestations of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

| Pulmonary | Ear, nose and throat | Other |

|---|---|---|

| Asthma Chronic bronchitis Bronchiectasis Pulmonary fibrosis Pneumonia | Chronic cough Laryngitis Hoarseness Pharyngitis Sinusitis Vocal cord granuloma Recurrent granuloma | Dental erosions Non-cardiac chest pain Sleep apnoea |

Adapted from Richter JE 2000 Extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. An overview. Am J Gastroenterol 95:51–53.

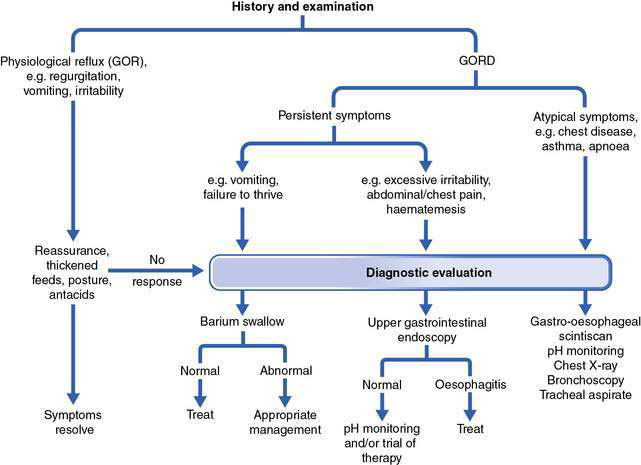

Diagnostic tests

Physiological GOR should be diagnosed on clinical grounds; diagnostic tests are not required. There is no single test for the diagnosis of GORD. If there are symptoms or signs of pathological reflux, such as pain, growth failure or respiratory symptoms, then further testing is required (Fig. 20.4.1). The test used will depend on the age of the child, the types of test available, and the type and severity of symptoms. The most commonly used tests are outlined in Box 20.4.3.

Fig. 20.4.1 Algorithm for diagnostic approach to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

(Modified from Youssef NN, Orenstein SR 2001 Clinical Perspectives in Gastroenterology Jan/Feb: 11–17.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree