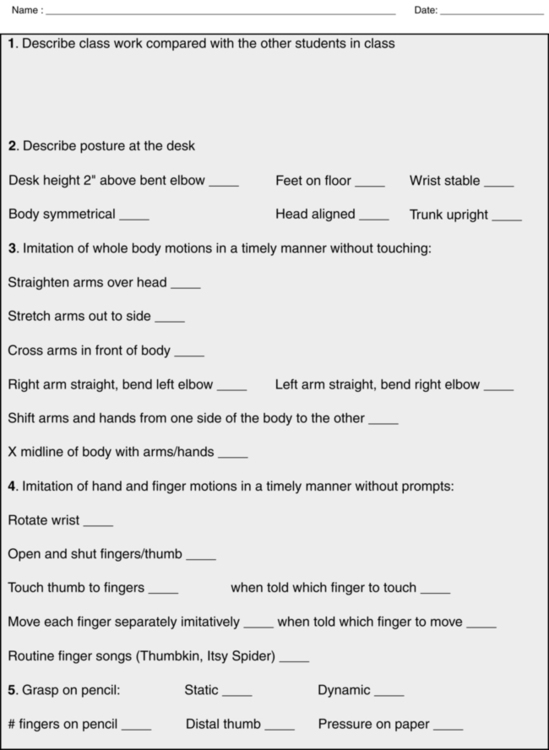

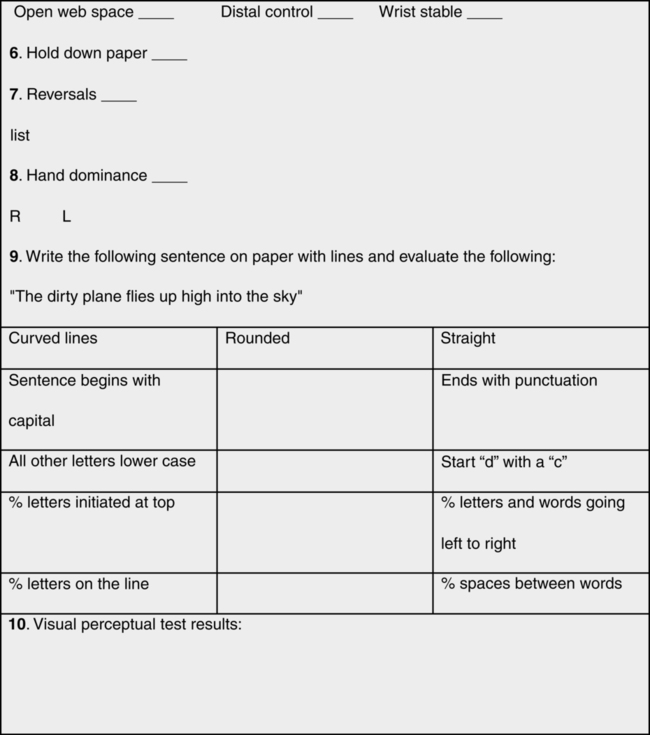

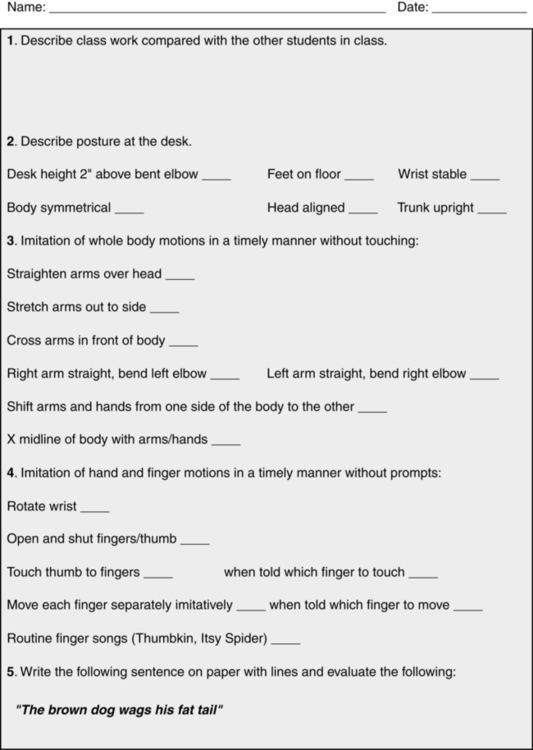

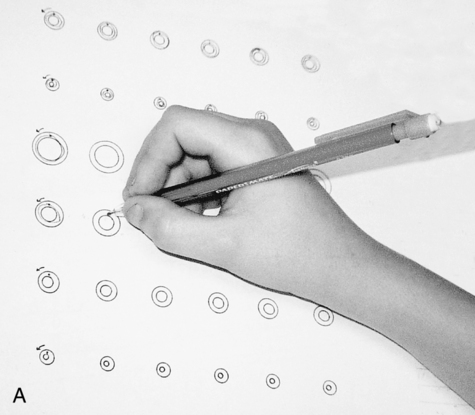

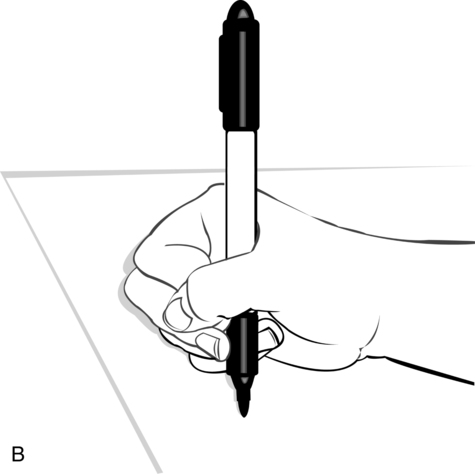

21 After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Identify prewriting strokes, their developmental sequence, and at what age they emerge • Explain how handwriting skills affect the ability of children to perform written assignments in the school setting • Recognize the client factors required for handwriting • Identify the reasons handwriting difficulties occur • Suggest strategies to improve handwriting or written expression • Describe direct intervention techniques • Describe how visual perception affects handwriting • Identify types of grasping patterns • Describe types of handwriting assessments used in pediatrics The most frequent referral for occupational therapists in the school setting is for problems with handwriting.4 As a result, handwriting remediation programs are often delivered on site at school, either individually or in small groups.13 Handwriting is one of the functional tasks required of a child in his or her occupation as student. McHale and Cermak report that as much as 60% of a school day can be spent on fine motor tasks, including handwriting.15 It is an important part of the educational process because handwriting is the most common means by which a student expresses knowledge of the material being taught. In addition, a student uses writing to summarize information taught in class, complete assignments, take tests, and interact with others for noneducational purposes.21 Between 10% and 30% of elementary school children struggle with handwriting.9 Likewise, experts claim that illegible handwriting has secondary effects on school achievement and self-esteem.7,14 Handwriting difficulties in children include illegible handwriting and speed-related issues; in addition, areas that affect the legibility of handwriting include letter formation, horizontal alignment, size, spacing, and slant.13,15,18 Handwriting is one of the tools teachers use to measure a student’s academic comprehension. Handwriting allows children to express themselves, learn information, organize their work, and communicate with others. It is vital that occupational therapy (OT) practitioners working in schools address handwriting difficulties to improve students’ performances in their occupation.15,18 Handwriting is an important occupational skill requiring motor, sensory, perceptual, and cognitive abilities.13 Formal and informal assessments of the ability to imitate and copy lines and shapes, hold a pencil or tool, and complete perceptual motor tasks help identify the factors for intervention. Figures 21-1 and 21-2 are examples of checklists which may be used to identify a child’s prerequisite skills for handwriting. Developmental assessments examine the developmental level of a child’s handwriting abilities. They provide OT practitioners with information concerning the age level at which the child performs. For example, in Molly’s situation, the assessment can answer the following question: Does Molly have the handwriting abilities required of a student in Grade 1? Box 21-1 provides sample developmental assessments. Visual perception is the ability to organize and interpret what is seen. Handwriting requires children to visually perceive the organization of letters and spacing between words. They must also determine the direction of letters (e.g., b compared with d). Visual perception is required to know where to start writing on the page, sequence the strokes of letters, and space words. When writing, children must recognize that the sizes of letters do not change the meanings of words. Molly may be experiencing poor visual perception. In this scenario, she is unable to make sense of how letters are formed. Molly may not recognize the differences among b, p, and d (Box 21-2). Visual perceptual tests examine the following skills: • Discrimination: The ability to detect a difference or distinction between one item or picture and another, for example, the ability to identify which picture is not like the others. • Visual Memory: The ability to remember a shape or word and recall the information when necessary. With handwriting, children must remember how to form letters, numbers, and shapes. In later school years, this skill is used when remembering how to form the letters to spell words or form multidigit numbers. • Form Constancy: The ability to realize and recognize that forms, letters, and numbers are the same or are constant whether they are moved, turned, or changed to a different size. This means that a square is always a square no matter what size or color. A daily example of this is when a person recalls the shape of the “yield” sign. • Sequential Memory: The ability to remember a sequence or chain of letters to form a word. With handwriting, children need motor as well as cognitive sequencing. Therefore, they need the ability to remember how letters make words and sequence them according to their motor abilities to make those words. For example, when taking a spelling test, the child needs to be able to recall what the word “dog” looks like and remember that it is d – o – g and not g – d – o. • Figure Ground: The ability to identify the foreground from the background. When looking at pictures, people, or items, it is essential to separate important visual aspects from the background. When writing, children identify written words on lined paper. An example of this is the game of finding hidden objects in a drawing. • Visual Closure: The ability to identify a form or object from its incomplete appearance. This enables a child to figure out objects, shapes, and forms by finishing the image mentally, for example, finding a jacket when it is partially covered by others. This ability is required when a letter may not be completely formed. A variety of different handwriting assessments that can be used to evaluate a child’s handwriting are available (Box 21-3). Assessments can be standardized or nonstandardized and include clinical observations. The evaluating OT practitioner needs to know the purpose of the evaluation. Do the results need to be standardized? Does the OT practitioner, parent, or teacher want to know where this child’s handwriting abilities are in comparison with his or her peers, or is getting an example of the child’s handwriting abilities the goal? Is the OT practitioner interested in learning how the child is writing or spacing letters and words? The nature of the evaluation will determine which type of assessment(s) is to be used. Children with handwriting difficulties show a less mature grasp, immature pencil grip, and inconsistent hand preference.3 The most mature grasps are the dynamic tripod (Figure 21-3, A) and lateral tripod grasps. By definition, in a tripod grasp three fingers are used for holding the writing utensil. The thumb is bent, the index finger points to the top of the writing utensil, and the writing utensil rests on the side of the middle finger. The last two fingers are curled in the palm and stabilize the hand.16 The lateral quadrupod and four-finger grip can be as functional as the dynamic tripod, lateral tripod, and dynamic quadrupod pencil grips in Grade 4 students.10 A quadrupod grip (four fingers) is another way children may hold their writing utensil. The thumb is bent, the index and middle finger point to the top of the writing utensil, and the writing utensil rests on the ring finger.16 In the dynamic tripod grasp, finger movements are used rather than those of the whole hand or arm. When forming a letter, dynamic movements of the fingers create smooth curves. Awkward grasping patterns result in poor letter formation, fatigue, and poor handwriting. Hank holds the pencil tightly with minimum web space and a cross-thumb grasp (see Figure 21-3, B). The resulting strain and contraction of the wrist and finger muscles may cause pain, fatigue, and discomfort. Knowledge of the progression of grasping patterns is useful to the OT practitioner in evaluating handwriting.18 Cross-thumb (thumb wrap) or static tripod grasps can be fatiguing or painful but offer more stability and power. Tight grasps limit the variety of movements and make smooth, flowing motions difficult. Writers using tight grasps often press hard on the paper, which results in the formation of dark, sometimes smeared, letters.18 As children grow and develop, so does their handwriting ability. Table 21-1 provides an outline of the sequence of writing development. The children’s ability to manipulate writing/coloring utensils as well as their ability to use their “helper hand” improves. As they become more comfortable with the task of scribbling, coloring, and ultimately writing, their posture during this task changes and matures. A 2-year-old uses all of his or her fingers to hold a crayon in the palm of the hand. The helping hand is of no use, as the upper extremity is usually retracted at the shoulder, flexed at the elbow, adducted to the side, with semicontracted fingers. This is a position of stability for the child. In addition, the hand performing the scribbling is abducted at the shoulder and flexed at the elbow, and the wrist is pronated and does not make contact with the paper at all. The posture of the 3-year-old is more advanced in that the child starts to use the helping hand. The shoulders are still elevated but are not as retracted. All of the fingers may still be used to hold the utensil, and the wrist of the dominant hand continues to be in the air. As the fourth year approaches, the utensil is being held with a more mature grasp. Shoulders are relaxing to a certain extent but continue to be elevated and somewhat retracted for stability. In addition, the child uses the helper hand to hold the paper in a more deliberate fashion. The elbow of the dominant hand is still elevated, and the writing hand still is not making contact with the surface of the table. By the fifth year, a mature grasp has evolved, and the dominant elbow, wrist, and hand all lie comfortably on the surface of the table. The shoulders are relaxed, and the child sits confidently at the table for handwriting and coloring activities. TABLE 21-1 In-hand manipulation refers to the precise and skilled finger movements made during fine motor tasks. In-hand manipulation is correlated with handwriting legibility.21 In order to perform in-hand manipulation tasks, the child needs to be able to adjust objects within the hand while maintaining the grasp on the object. A general example of this skill is working coins from the palm of the hand to a pincer grasp to deposit the coins into a piggy bank. In-hand manipulation skills during writing are observed when a child rotates the pencil to use the eraser. Another example is manipulating the pencil to write dynamically with a tripod grasp while the ring and little fingers remain still to stabilize the hand. In-hand manipulation requires strength, timing, and coordination. Examples of exercises that can strengthen the intrinsic muscles of the hand for improved in-hand manipulation include the following: • Shifting: working items from the palm of the hand to the tips of the fingers without dropping items • Translation: using only the fingers, the student “walks” his or her hand from the lead end of the pencil to the eraser end without the aid of items for stabilization • Rotation: turning the pencil from the lead end to the eraser end without putting the pencil down on the table or using the chest to stabilize the pencil while turning it.

Functional task at school: handwriting

Evaluation and assessment of handwriting skills

Standardized/nonstandardized assessments and classroom observation

Developmental assessments

Visual perception assessments

Handwriting assessments

Developmental sequence

Grasping patterns

Developmental stages in writing readiness

ITEM NAME

AGE (MONTHS)

Stirring spoon

12

Scribbling—1 scribble 1 inch long

14

Imitating vertical line 2 inches long

23-24

Imitating horizontal line 2 inches long

27-28

Copying circle—end points within half inch of each other

33-34

Copying cross—intersecting lines within 20 degrees of perpendicular

39-40

Tracing line—deviates <2 times

41-42

In-hand manipulation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Functional task at school: handwriting

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue