CHAPTER 57 Fistulae

Aetiology and Epidemiology

The aetiology of urogenital fistulae is varied, and may be broadly categorized into congenital or acquired, the latter being divided into obstetric, surgical, radiation, malignant and miscellaneous causes. The same factors may be responsible for intestinogenital fistulae, although inflammatory bowel disease is an additional important aetiological factor here. In most developing countries, over 90% of fistulae are of obstetric aetiology, whereas in the UK, approximately 70% follow pelvic surgery (Table 57.1).

Table 57.1 Aetiology of urogenital fistulae in two series from the north-east of England (Hilton unpublished) and from south-east Nigeria (Hilton and Ward 1998)

| Aetiology | North-east England (n = 300) | South-east Nigeria (n = 2389) |

|---|---|---|

| Obstetric | ||

| Obstructed labour | 2 | 1918 |

| Caesarean section | 13 | 165 |

| Ruptured uterus | 8 | 119 |

| Forceps/ventouse | 5 | |

| Breech extraction | 1 | |

| Placental abruption | 1 | |

| Caesarean hysterectomy | 3 | |

| Symphysiotomy | 2 | |

| Obstetric subtotal (% of total) | 35 (11.7%) | 2202 (92.2%) |

| Surgical | ||

| Abdominal hysterectomy | 120 | 33 |

| Radical hysterectomy | 15 | |

| Urethral diverticulectomy | 15 | |

| Colectomy | 9 | |

| Colporrhaphy | 9 | 35 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 5 | 25 |

| Midurethral tape procedures | 4 | |

| Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy | 3 | |

| Cystoplasty and colposuspension | 2 | |

| Colposuspension | 2 | |

| Cervical stumpectomy | 2 | |

| Large loop excision of the transformation zone | 2 | |

| Nephroureterectomy | 2 | |

| Subtotal hysterectomy | 2 | |

| Total abdominal hysterectomy and colporrhaphy | 1 | |

| Total abdominal hysterectomy and colposuspension | 1 | |

| Laparoscopic oophorectomy | 1 | |

| Sling | 2 | |

| Partial vaginectomy | 3 | |

| Periurethral bulking agents | 1 | |

| Needle suspension | 1 | |

| Subtrigonal phenol injection | 1 | |

| Lithocast | 1 | |

| Ileoanal pouch | 1 | |

| Sacrospinous fixation | 1 | |

| Unknown surgery in childhood | 1 | |

| Suture to vaginal laceration | 12 | |

| Surgical subtotal (% of total) | 207 (69.0%) | 105 (4.4%) |

| Radiation | ||

| Radiation subtotal (% of total) | 28 (9.3%) | 0 |

| Malignancy | ||

| Malignancy subtotal (% of total) | 2 (0.7%) | 42 (1.8%) |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| Vaginal pessary | 8 | |

| Infection | 5 | 7 |

| Congenital | 5 | |

| Foreign body | 4 | |

| Catheter induced | 3 | |

| Trauma | 2 | 11 |

| Coital injury | 1 | 22 |

| Miscellaneous subtotal (% of total) | 28 (9.3%) | 40 (1.7%) |

Sources: Hilton (unpublished).

Hilton P, Ward A 1998 Epidemiological and surgical aspects of urogenital fistulae: a review of 25 years experience in south-east Nigeria. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction 9: 189–194.

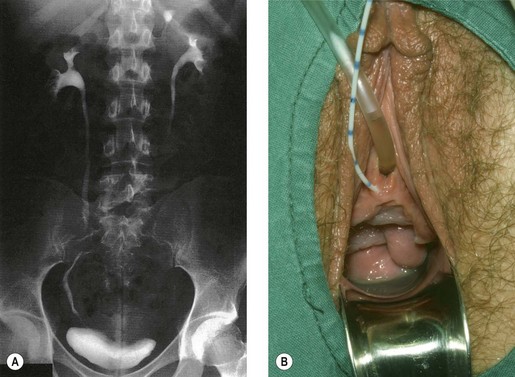

Congenital fistulae are strictly outside the scope of this chapter, and readers are advised to refer to Chapter 13 for further information. Some cases of ectopic ureter may discharge into the vagina, and their presentation may be delayed into teens or adult life, hence leading to confusion with acquired fistulae or other causes of incontinence. This occurs particularly if the abnormal ureter is only draining a small or poorly functioning part of the renal tissue. Under these circumstances, the abnormal tissue may be insufficient to show up as a soft tissue shadow on a plain X-ray, and so poorly functional that it is not easily seen on excretion urography. A high index of clinical suspicion is required if the diagnosis is not to be overlooked (Figure 57.1A,B).

Obstetric

The overwhelming majority are complications of neglected obstructed labour. During normal labour, the bladder is displaced upwards and the anterior vaginal wall, bladder base and urethra are compressed between the fetal head and the posterior surface of the pubis. No harm results if this occurs for a short time, but in prolonged obstructed labour, the intervening tissues are devitalized by ischaemia. Usually, the anterior vaginal wall and underlying bladder neck are affected, although the area of necrosis is sometimes higher, in which case the anterior lip of the cervix and underlying trigone are involved. Compression of the soft tissues between the sacral promontory and the presenting part may occur at the same time, with necrosis at the posterior vaginal wall and underlying rectum. The devitalized area separates as a slough usually between the third and 10th day of the puerperium, with resulting incontinence (Figure 57.2).

The perineum and posterior vaginal wall are, of course, at risk from even the most straightforward delivery, although primiparity, forceps delivery, birth weight over 4 kg and occipitoposterior position have been found to be significant risk factors associated with third-degree tears (Sultan et al 1994). Even when identified and repaired, this increases the risk of rectovaginal fistula.

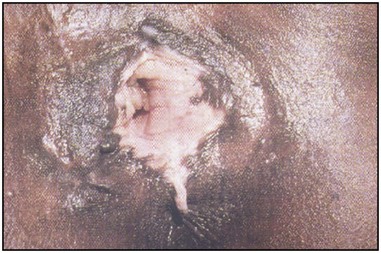

Traditional surgical practices are undertaken in up to 98% of women in some parts of Africa (United Nations Population Fund 2007, World Health Organization 2008), and may play a role in the aetiology of both direct ‘surgical’ and obstetric fistulae. The practices of ‘angurya’ and ‘gishiri’ cutting [female genital mutilation (FGM) type IV] (World Health Organization 2008) are commonly employed to treat a wide variety of conditions including obstructed labour, infertility, dyspareunia, dysuria, amenorrhoea, goitre, backache and presumed tumour. The traditional cut made with a razor blade or knife through the vaginal introitus is sometimes superficial, but may result in fistula formation (Figure 57.3). Since cuts are usually made by linear incision into healthy tissues, repair is often much easier than for those resulting from pressure necrosis. Tahzib (1983, 1985) reported on the epidemiological determinants of vesicovaginal fistulae in northern Nigeria. In 84% of cases, obstructed labour was the major aetiological factor, 33% had undergone ‘gishiri’, and this was felt to be the main aetiological factor in 15%.

Figure 57.3 Vesicovaginal fistula resulting from ‘gishiri’ cutting (female genital mutilation type IV).

Female circumcision has been practised in various forms in much of North Africa, being most prevalent in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Mali and Guinea, where currently over 75% of women are affected (World Health Organization 2008). The more extreme forms (previously referred to as ‘pharaonic circumcision’) involve removal of the labial minora (FGM type IIa), and may include removal of the clitoris (FGM type IIb) and labia majora (FGM type IIc) (see Figure 57.4). In FGM type III, the introitus may be reduced to pin-hole size by excision and apposition of the cut edges of the labia minora or majora (infibulation) (World Health Organization 2008). Whilst an association between FGM and both vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula is recognized (Lovel et al 2000), the strength of the association and the exact mechanisms are less certain and are currently under investigation (World Health Organization 2008).

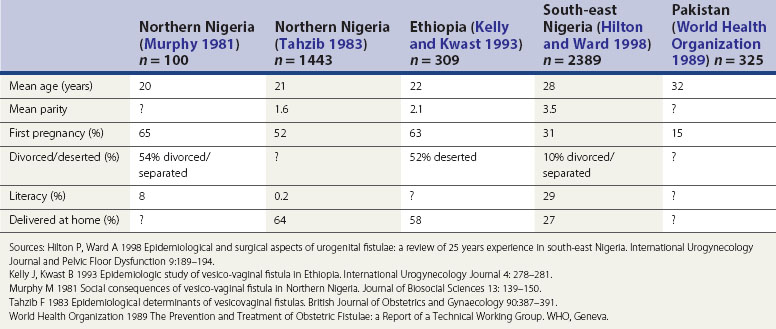

The influence of these factors is illustrated in the epidemiological studies alluded to earlier. Tahzib (1983) reported that over 50% of the cases of vesicovaginal fistulae seen in northern Nigeria were under 20 years of age, over 50% were in their first pregnancy, and only one in 500 had received any formal education. From the same area, Murphy (1981) reported that 88% of patients had married at 15 years of age or less, and 33% had delivered their first child before the age of 15 years. However, in different developing world societies, these factors do seem to have variable influence. For example, in south-east Nigeria (Hilton and Ward 1998) and the north-west frontier of Pakistan (World Health Organization 1989), fistula patients seem to be somewhat older and of higher parity; they also appear to have a higher literacy rate, and to be more likely to remain in a married relationship after the development of their fistula (Hilton and Ward 1998). It is likely that the development of fistulae here reflects other biosocial variations (Table 57.2). It is clear that in these populations, even where skilled maternity care is available, uptake may be poor. Mistrust of hospitals is commonplace, antenatal care is poorly attended, and delivery is commonly conducted at home by elderly relatives or unskilled traditional birth attendants. Where labour is prolonged, transfer to hospital may only be used as a last resort.

Surgical

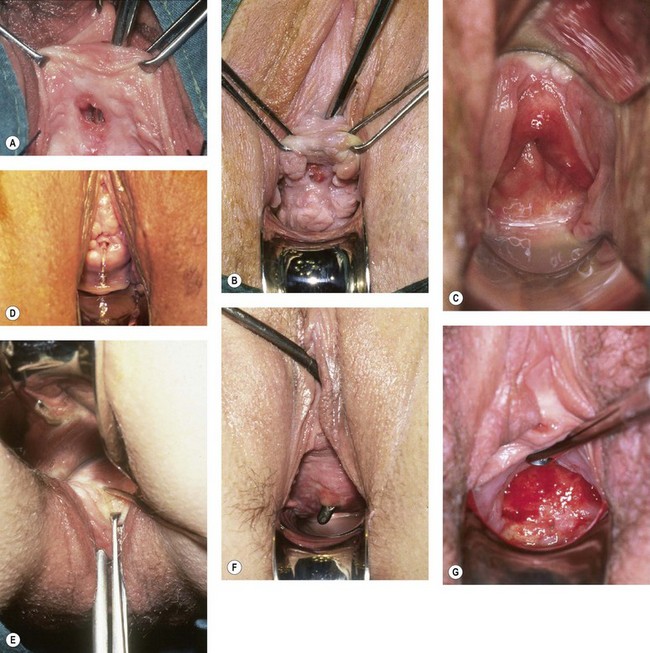

Genital fistula may occur following a wide range of surgical procedures within the pelvis (Table 57.1, Figure 57.5A–F). It is often supposed that this complication results from direct injury to the lower urinary tract at the time of operation. Certainly, on occasions, this may be the case; careless, hurried or rough surgical technique makes injury to the lower urinary tract much more likely. However, of 300 fistulae referred to the author in the UK over the last 20 years, 207 have been associated with pelvic surgery and 147 followed hysterectomy; of these, only seven presented with leakage of urine on the first postoperative day. In other cases, compromise to the blood supply may result in tissue necrosis and subsequent leakage; alternatively, a small pelvic haematoma may develop in association with the vaginal vault, which subsequently becomes infected and discharges with the characteristic puff of haematuria 5–10 days later, with incontinence following shortly thereafter. Recent animal studies suggest that the inadvertent placement of vault sutures into the bladder wall at hysterectomy may not carry as great a risk of fistula formation as previously thought (Meeks et al 1997).

Although it is important to remember that the majority of surgical fistulae follow apparently straightforward hysterectomy in skilled hands, several risk factors may be identified that make direct injury more likely (Table 57.3). Obviously, anatomical distortion within the pelvis by ovarian tumour or fibroid will increase surgical difficulty, and abnormal adhesions between bladder and uterus or cervix following previous surgery or associated with previous sepsis, endometriosis or malignancy may make fistula formation more likely. Preoperative or early postoperative radiotherapy may decrease vascularity, and make the tissues generally less forgiving of poor technique.

Table 57.3 Risk factors for postoperative fistulae

| Risk factor | Pathology | Specific example |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomical distortion | Fibroids | |

| Ovarian mass | ||

| Abnormal tissue adhesion | Inflammation | Infection |

| Endometriosis | ||

| Previous surgery | Caesarean section | |

| Cone biopsy | ||

| Colporrhaphy | ||

| Malignancy | ||

| Impaired vascularity | Ionizing radiation | Preoperative radiotherapy |

| Metabolic abnormality | Diabetes mellitus | |

| Radical surgery | ||

| Compromised healing | Anaemia | |

| Nutritional deficiency | ||

| Abnormality of bladder function | Voiding dysfunction |

Sources: Hilton P, Ward A 1998 Epidemiological and surgical aspects of urogenital fistulae: a review of 25 years experience in south-east Nigeria. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction 9: 189–194.

Kelly J, Kwast B 1993 Epidemiologic study of vesico-vaginal fistula in Ethiopia. International Urogynecology Journal 4: 278–281.

Murphy M 1981 Social consequences of vesico-vaginal fistula in Northern Nigeria. Journal of Biosocial Sciences 13: 139–150.

Tahzib F 1983 Epidemiological determinants of vesicovaginal fistulas. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 90: 387–391.

World Health Organization 1989 The Prevention and Treatment of Obstetric Fistulae: a Report of a Technical Working Group. WHO, Geneva.

It has recently been shown that there is a high incidence of abnormalities of lower urinary tract function in fistula patients (Hilton 1998); whether these abnormalities antedate the surgery, or develop with or as a consequence of the fistula, cannot be answered from this data. However, it is likely that patients with a habit of infrequent voiding, or with inefficient detrusor contractility, may be at increased risk of postoperative urinary retention; if this is not recognized early and managed appropriately, the risk of fistula formation may be increased.

Radiation

As noted above, preoperative pelvic irradiation increases the risk of postoperative fistula development, but irradiation itself may be a cause of fistula (Figure 57.5G). The obliterative endarteritis associated with ionizing radiation in therapeutic dosage proceeds over many years, and may be aetiological in fistula formation long after the primary malignancy has been treated. Of the 28 radiation fistulae in the author’s series, the fistulae developed at intervals between 1 and 30 years following radiotherapy. Not only does this ischaemia produce the fistulae, it also causes significant damage in the adjacent tissues, so ordinary surgical repair has a high likelihood of failure and modified surgical techniques are required.

Inflammatory bowel disease

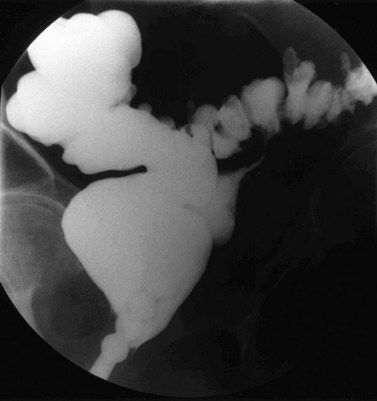

Ulcerative colitis has a small incidence of low rectovaginal fistulae. Diverticular disease can produce colovaginal fistulae and, rarely, colouterine fistulae, with surprisingly few symptoms attributable to the intestinal pathology. The possibility should not be overlooked if an elderly woman complains of feculent discharge or becomes incontinent without concomitant urinary problems (Figure 57.6).

Prevalence

United Kingdom

The prevalence of genital fistulae obviously varies from country to country and continent to continent as the main causative factors vary. Accurate figures are impossible to obtain since those areas with the highest overall prevalence are also those with the poorest systems of health data collection. UK National Health Service data reported approximately 150 operations for vesicovaginal and urethrovaginal fistula per year in England and Wales in the early 1990s (Hilton 1997). The most recent data from Health Episode Statistics for England suggest an average of 95 operations for vesicovaginal fistula and 10 operations for urethrovaginal fistula per year in England (Department of Health 2009). It is tempting to suggest that this apparent reduction in incidence of fistulae may reflect changes in the practice of hysterectomy. However, assuming that 50% of urogenital fistulae in the UK follow hysterectomy (as in the author’s series), the rate of fistula formation following hysterectomy seems, if anything, to be increasing; from approximately one in 1200 hysterectomies in the period 1990–1991 to 1994–1995 to approximately one in 750 in 2003–2004 to 2007–2008 (Department of Health 2009). Whilst there are other possible explanations, it may be that as fewer hysterectomies are undertaken, those that remain are the more difficult procedures. Studies from Finland suggest a similar rate of posthysterectomy fistulae overall, with approximately one per 1000 abdominal hysterectomies and one per 450 laparoscopic hysterectomies (Harkki-Siren et al 1998). Similarly, ureteric injury may be up to six times as common following laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with open hysterectomy (Harkki-Siren et al 1998), and two to 10 times as common following radical hysterectomy and exenteration (Averette et al 1993, Bladou et al 1995, Emmert and Köhler 1996). Sultan et al (1994) reported that third-degree tears followed 0.6% of vaginal deliveries, and a rectovaginal fistula resulted in 6% of these (one in 3000 deliveries overall).

Developing world

In the developing world, many fistula cases are unknown to medical services, being separated from their husbands and ostracized from society. Although the true prevalence in the developing world is unknown, particularly high prevalence rates are reported in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sudan and Chad. The estimated prevalence in the developing world is one to two per 1000 deliveries, with perhaps 50,000–100,000 new cases each year. Although several units exist in Nigeria, Ethiopia and Sudan, which deal with 100–700 cases per year, this does not come close to meeting the demand, and there are estimated to be perhaps 500,000 to 2 million untreated cases worldwide (Waaldijk and Armiya’u 1993).

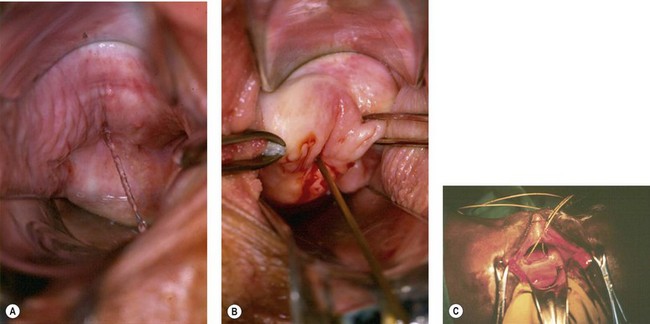

Classification

Many different fistula classifications have been described in the literature on the basis of anatomical site or position in relation to meatus or sphincter mechanism; these are often subclassified into simple cases (where the tissues are healthy and access is good) (Figure 57.7A,B) or complicated cases (where there is tissue loss, scarring, impaired access, involvement of the ureteric orifices, or the presence of coexistent rectovaginal fistula) (Figure 57.7C) (Lawson 1978, Waaldijk 1995, Goh 2004). Urogenital fistulae may be classified into urethral, bladder neck, subsymphysial (a complex form involving circumferential loss of the urethra with fixity to bone), midvaginal, juxtacervical or vault fistulae; massive fistulae extending from bladder neck to vault; and vesicouterine or vesicocervical fistulae. It is interesting to note that whereas over 60% of fistulae in the developing world are midvaginal, juxtacervical or massive (reflecting their obstetric aetiology) (Hilton and Ward 1998), such cases are relatively rare in Western fistula practice; in contrast, 50% of the fistulae managed in the UK are situated in the vaginal vault (reflecting their surgical aetiology). There have been recent calls for classification systems more predictive of outcome (Arrowsmith 2007, Goh et al 2008).

Presentation

Occasionally, a patient with an obvious fistula may deny incontinence, and this is presumed to reflect the ability of the levator ani muscles to occlude the vagina below the level of the fistula. Some patients with vesicocervical or vesicouterine fistula following caesarean section may maintain continence at the level of the uterine isthmus, and complain of cyclical haematuria at the time of menstruation, or menouria (Falk and Tancer 1956, Youssef 1957). In other cases, patients may complain of little more than a watery vaginal discharge, or intermittent leakage, which seems posturally related. Leakage may appear to occur specifically on standing or on lying supine, prone, or in left or right lateral positions, presumably reflecting the degree of bladder distension and the position of the fistula within the bladder; such a pattern is most unlikely to be found with ureteric fistulae.

Although in the case of direct surgical injury, leakage may occur from the first postoperative day, in most surgical and obstetric fistulae, symptoms develop between 5 and 14 days after the causative injury; however, the time of presentation may be quite variable. This will depend, to some extent, on the severity of symptoms, but as far as obstetric fistulae in the developing world are concerned, is determined more by access to health care. In a review of cases from Nigeria, the average time for presentation was over 5 years, and in some cases over 35 years, after the causative pregnancy (Hilton and Ward 1998).

Ureteric fistulae occur from similar aetiologies to bladder fistulae, and the causative mechanism may be one of direct injury by incision, division or excision, or of ischaemia from strangulation by suture, crushing by clamp or stripping by dissection (Yeates 1987

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree