Chapter 43 Fever and Rash (Case 13)

Patient Care

History

• Review symptom onset and progression. Include activity level, fluid intake, and urination to assess hydration status and determine clues to etiology.

• An incompletely immunized child may be at risk for a vaccine-preventable disease such as varicella or measles.

• Timing of the rash may suggest etiology (e.g., several days of fever precedes rash in RMSF and roseola).

• Elicit rash distribution and progression. Scarlet fever rash begins on the face and spreads caudally. The lesions of RMSF begin on the distal extremities, involve palmar and solar surfaces, and spread centripetally. Morphology is also important. A maculopapular rash that becomes petechial or purpuric within several hours suggests meningococcemia.

Physical Examination

• Evaluate ABCs. Note general appearance, color, and mental status. Check for increased work of breathing; assess perfusion by checking capillary refill and pulses.

• Vital signs: Tachycardia is a sign of compensated shock. Hypotension signifies decompensated shock (see Chapter 84, Shock).

• Pay close attention to oral mucosa. Bright red lips or strawberry tongue suggest Kawasaki disease. Ulcerative lesions of erythema multiforme (EM) or vesicles of enterovirus are diagnostic clues.

• Note altered mental status (confusion, agitation, or lethargy) and meningeal signs such as a positive Kernig or Brudzinski sign.

• Perform a complete joint examination. There may be a painless joint effusion in Lyme disease. Joint swelling, warmth, morning stiffness or pain may occur in rheumatologic processes such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Tests for Consideration

• Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: Leukopenia suggests overwhelming infection or viral suppression; leukocytosis and thrombocytosis are nonspecific for infection; thrombocytopenia in sepsis, RMSF, and ehrlichiosis; and thrombocytosis in Kawasaki disease $116

• Liver transaminase levels: Elevated levels may signal organ inflammation or inadequate perfusion $132

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): To monitor inflammatory response in HSP or Kawasaki disease $85

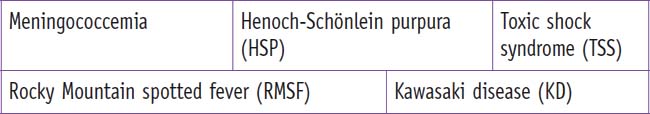

Clinical Entities: Medical Knowledge

| Meningococcemia | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Neisseria meningitidis is a gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the nasopharynx of approximately 5% of the population, and transmission is via respiratory droplets. Bacteremia and meningitis are forms of invasive disease with a mortality rate up to 10%. Meningococcal endotoxins cause extensive capillary injury, which results in the characteristic hemorrhagic rash and can progress to uncompensated shock and death. Extremity necrosis is a common and devastating sequela of fulminant meningococcemia. |

| TP | Peak incidence occurs under 1 year and in middle to late adolescence. A brief nonspecific febrile prodrome precedes high fevers, mental status change, petechial or purpuric rash, and hypotension. |

| Dx | Diagnosis is supported by gram-negative cocci on Gram stain of the blood or spinal fluid, and cultures are confirmatory. |

| Tx | Supportive treatment consists of ventilation, oxygenation, and hemodynamic support. Ceftriaxone and vancomycin are preferred empirical therapy. If cultures confirm meningococcemia, coverage can be narrowed to penicillin G for 7 to 14 days.1 See Nelson Essentials 100. |

| Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | RMSF is a tick-borne illness caused by Rickettsia rickettsii, a gram-negative coccobacillus that infects the small vessels of all tissues and organs, producing an infectious vasculitis. Host immune response contributes to diffuse vascular damage. |

| TP | This entity is commonly confused with meningococcemia; clinical presentation is quite similar. Clues to distinguish RMSF from meningococcemia are high fevers preceding rash for several days, distal extremity petechial rash spreading centrally to include palms and soles, and travel to an endemic area. High prevalence areas in the United States include the mid-Atlantic, Southern, and south-central states. RMSF has a seasonal predilection for April through September. |

| Dx | Diagnosis is often made clinically with supportive laboratory data, such as hyponatremia, hypoalbuminemia, elevated transaminases, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. Antibody titers to Rickettsia species are insensitive; comparative acute and convalescent antibody titers may be more helpful. |

| Tx | Doxycycline is the treatment of choice for this life-threatening illness and should be started once RMSF is suspected, with supportive treatment as needed.1 See Nelson Essentials 122. |

| Toxic Shock Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Gram positive bacteria, typically Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, produce toxins that cause a characteristic “erythroderma” rash, fever, tachycardia, and possibly hypotension as a result of toxin-mediated vasodilation. |

| TP | Patients present with a diffuse red macular tender rash (which later undergoes desquamation), fever, and possible alteration of mental status or other signs of inadequate perfusion, such as oliguria. Females may have a history of tampon use. |

| Dx | Diagnosis is clinical; namely, fever, the specific appearance of the rash, and signs of compensated shock (tachycardia), or decompensated shock (hypotension). Creatinine and liver transaminases may be elevated. Bacterial cultures are rarely positive, because toxins are responsible for clinical manifestations. |

| TX | Intravenous antibiotics are promptly begun with a two-drug regimen: A bactericidal agent interfering with cell wall synthesis, such as a beta-lactam, and another targeting ribosomal toxin production, such as clindamycin. Intravenous fluids and cardiorespiratory monitoring are provided as needed.1 See Nelson Essentials 97. |

| Kawasaki Disease | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | KD represents a febrile multisystem vasculitis with preferential involvement of medium-size arteries. Inflammation may involve all three layers of the vessel wall, with possible aneurysm formation. An infectious etiology has been postulated. |

| TP | The child is extremely irritable. In classic Kawasaki disease, there is fever for at least 5 days, with at least four of the following: < div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|