Chapter 33 Fever

ETIOLOGY

What Is “Fever without Source?”

Fever without source refers to the situation when history and physical examination can find no obvious cause for fever. Most such patients have a viral illness, but when fever is above 40° C (104° F), immunizations are incomplete, and the child appears “toxic,” the risk of a serious bacterial illness is high. The differential diagnosis includes urinary tract infection, bacteremia, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, and meningitis, all of which may be difficult to diagnose in the infant and young child. The risk that the fever represents bacteremia and meningitis has fallen dramatically since introduction of the conjugate vaccines for Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (PCV-7) (see Chapters 12 and 64). Urinary tract infection (Chapter 65) is the most common bacterial cause of fever without source in young children, especially girls. Osteomyelitis may be challenging to diagnose early in its course. Fever may be the first manifestation of Kawasaki disease, a malignancy, or a rheumatologic disorder.

EVALUATION

How Should I Evaluate a Febrile Child?

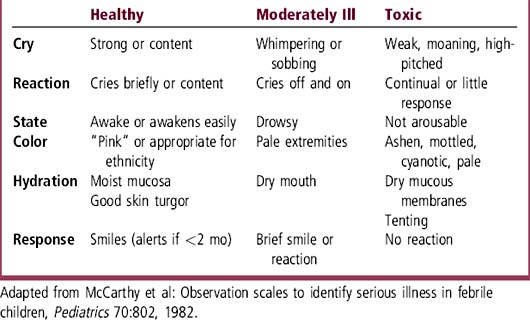

First, use history to elicit symptoms and to characterize the illness pattern, duration, and perceived severity. Ask parents about their observations and concerns. Review the child’s risk factors, especially immunization status and exposures such as daycare. Consider any past history of fever, infection, antibiotic treatment, and recurrent or chronic disease. Observe the ill child before beginning the hands-on physical examination to identify signs of toxicity (Table 33-1). Perform a careful physical examination with the goal of identifying a source of infection or a disease that can explain the findings. Use laboratory tests and imaging judiciously.

What Increases the Risk of Serious Bacterial Infection?

Age: The highest risk of serious infection is in the newborn period (birth to 1 month). Premature infants have higher risk than full-term infants. Infections may result from birth-related events, so history must ask about maternal infections (especially group B Streptococcus), pregnancy, labor, delivery, and the postnatal period. The next highest risk period is from 1 to 3 months, especially before immunizations begin. Risk decreases from 3 months to 3 years, even though fever is most common in this age group. Risk of serious bacterial illness declines further after age 3 years, but meningococcal disease does occur sporadically in children and adolescents.

Age: The highest risk of serious infection is in the newborn period (birth to 1 month). Premature infants have higher risk than full-term infants. Infections may result from birth-related events, so history must ask about maternal infections (especially group B Streptococcus), pregnancy, labor, delivery, and the postnatal period. The next highest risk period is from 1 to 3 months, especially before immunizations begin. Risk decreases from 3 months to 3 years, even though fever is most common in this age group. Risk of serious bacterial illness declines further after age 3 years, but meningococcal disease does occur sporadically in children and adolescents.

Toxicity: This clinical appearance (see below) correlates with serious bacterial illness, but the absence of toxicity in a highly febrile infant or young child is no guarantee that infection is absent. Other risk factors such as age and immunization status should be taken into account.

Toxicity: This clinical appearance (see below) correlates with serious bacterial illness, but the absence of toxicity in a highly febrile infant or young child is no guarantee that infection is absent. Other risk factors such as age and immunization status should be taken into account.

Height of the fever: Before introduction of Hib and PCV-7 vaccines, fever > 40° C (> 104° F) was highly correlated with serious bacterial infection. Although the risk of infection with H. influenzae type b and S. pneumoniae is now < 1% in immunized children, high fever plus concerning clinical findings should always be taken seriously and prompt a careful evaluation. Invasive tests may be less necessary now than in the past, however, if the child is fully immunized.

Height of the fever: Before introduction of Hib and PCV-7 vaccines, fever > 40° C (> 104° F) was highly correlated with serious bacterial infection. Although the risk of infection with H. influenzae type b and S. pneumoniae is now < 1% in immunized children, high fever plus concerning clinical findings should always be taken seriously and prompt a careful evaluation. Invasive tests may be less necessary now than in the past, however, if the child is fully immunized.

Immunizations: Children who have not received Hib and PCV-7 immunizations are at highest risk for serious infection. In addition, immunization against influenza virus helps prevent this extremely contagious infection in children and reduces disease in adults. The new conjugate meningococcal vaccine should reduce this disease in adolescents.

Immunizations: Children who have not received Hib and PCV-7 immunizations are at highest risk for serious infection. In addition, immunization against influenza virus helps prevent this extremely contagious infection in children and reduces disease in adults. The new conjugate meningococcal vaccine should reduce this disease in adolescents.

Exposure or other risk factors: Daycare, school, and home are common sites for exposure to infection. The family history of acute illnesses and immune deficiencies should be addressed. In addition, a child with an underlying disease such as sickle cell anemia may be predisposed to infection.

Exposure or other risk factors: Daycare, school, and home are common sites for exposure to infection. The family history of acute illnesses and immune deficiencies should be addressed. In addition, a child with an underlying disease such as sickle cell anemia may be predisposed to infection.

Previous infections and previous treatment with antibiotics increase the risk of infection with antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Previous infections and previous treatment with antibiotics increase the risk of infection with antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Epidemiology: Infections present in the community, such as viral influenza and Neisseria meningitidis, may explain fever. Knowledge of infectious disease activity in the community can focus the differential diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment.

Epidemiology: Infections present in the community, such as viral influenza and Neisseria meningitidis, may explain fever. Knowledge of infectious disease activity in the community can focus the differential diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree