Introduction

Sexuality plays an integral role throughout a woman’s life. Multiple disparate factors influence sexuality and sexual health, including general health, psychologic status, interpersonal relationships, anatomy, hormonal patterns, and cultural mores.

Physiology

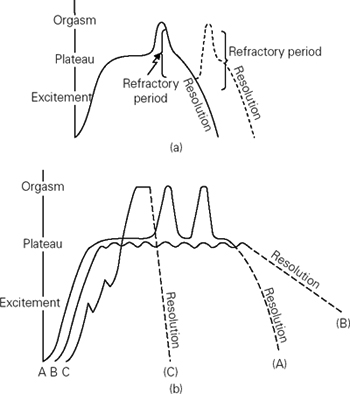

There are several basic models that form the foundation of our current knowledge of the female sexual response. Masters & Johnson established the classic paradigm with the publication of Human sexual response in 1966. In it, they observed the sexual activity of 700 subjects, and delineated four stages of sexual response: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution (Figure 68.1).

Figure 68.1 The sexual response in (a) men and (b) women. The curves represent degrees of sexual arousal. The three different female cycle patterns in (b) are discussed in the text. Reproduced from Jones RE. Human reproductive biology, 2nd edn. San Diego: Academic Press, 1997.

As noted in Figure 68.1, female sexual response patterns may differ from woman to woman and from one sexual encounter to another. This is typically considered a linear model and one pattern (A) corresponds the most with the male sexual response, but with a longer plateau phase and the possibility of multiple orgasms (without the male refractory period). Another pattern (B) has no orgasm stage but instead, a prolonged plateau phase with several peaks and troughs, finally culminating in the resolution stage. The final pattern (C) has a rapid shift from the excitement phase to orgasm, followed by quick resolution.

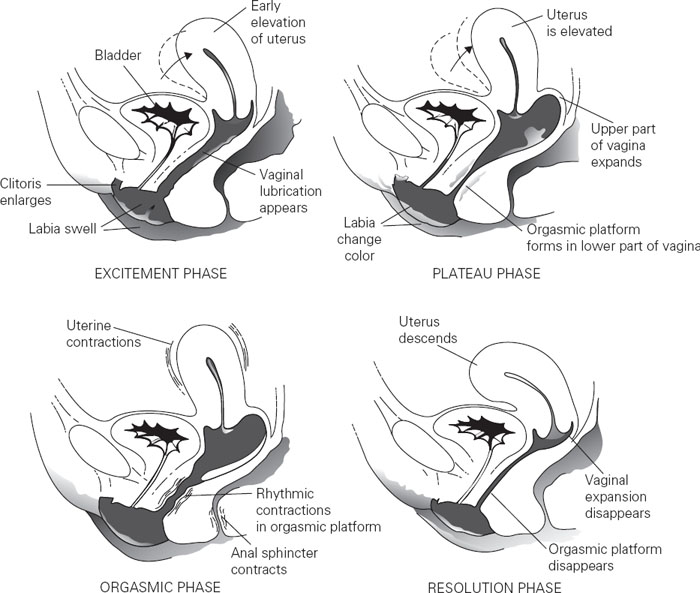

Excitement is the first stage and can be initiated via external or internal stimuli (Figure 68.2). This phase is mediated initially by the central nervous system, via stimulation of the parasympathetic autonomic nervous system. This in turn increases blood flow and smooth muscle relaxation throughout the body. There is generalized vasocongestion, hyperventilation, hypertension, and tachycardia. The labia majora increase to 2–3 times their nonaroused size in all women. In nulliparous women, the labia majora become tauter and thinner. The established and extensive vascular channels in multiparous women cause the labia majora to swell. The clitoris also engorges during the excitement phase. Both the clitoral glans and the shaft (also known as the prepuce) increase in diameter. The deep tissues of the vagina begin producing a clear transudate within 10–30 seconds after the initiation of sexual arousal. This fluid not only facilitates intercourse but also neutralizes vaginal pH, thereby assisting in survival of sperm. Skin flushing may occur over the body, especially the face, neck, back, and breasts. The breasts enlarge, as does the areola. Nipple erection is an early sign of sexual excitement.

Figure 68.2 Changes in the female sex organs during the sexual response cycle. Adapted from Masters WH, Johnson VE, Kolodny RC. Biological foundations of human sexuality. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers, 1993.

The plateau phase is the peak of the excitement phase. The parasympathetic system continues to dominate throughout this time. Further changes take place in the proximal vagina – specifically, expansion of the posterior fornix. This occurs in preparation for the volume of semen deposited with ejaculation. The entire vagina lengthens during this phase. In the lower vagina, an orgasmic platform is formed through vasocongestion of the perineal, bulbocavernosus, and pubococcygeus muscles. This platform decreases the transverse vaginal diameter, leading to increased friction during intercourse. The uterus becomes engorged during both the excitement and plateau stages. It lifts upward during the plateau phase. This tenting of the uterus possibly is due to Valsalva maneuvers during intercourse.

Orgasm represents the third stage of sexual response and is regulated by the sympathetic autonomic nervous system. It is the peak of sexual pleasure and is described as the release of sexual tension. Physiologically, the uterus, orgasmic platform, and anal sphincter rhythmically contract. These spasms commence about 2–4 seconds after the woman senses the orgasm, and occur on average at 0.8-second intervals (although this period becomes longer at the end of the orgasm). Usually, there are 3–15 contractions noted. The contractions are initially intense and gradually become weaker as the orgasm subsides. Associated generalized myotonic contraction may also occur. The proximal vagina continues expanding during orgasm. The clitoris retracts under its hood behind the symphysis pubis and flattens. In 10–40% of women fluid may be expelled from the Skene’s glands.

Resolution represents the final phase in the sexual response cycle and involves the return of the genitopelvic anatomy to the nonaroused state. Mental and physical relaxation predominate, and the woman experiences a sense of euphoria and well-being. Women may not experience a refractory period, and thus can be stimulated to experience several sexual orgasms in repeated cycles in one session.

The second theory of female sexual response adds the concept of sexual desire and it was first introduced by Helen Kaplan Singer. Desire is a common prelude to sexual response, though not a necessary stage. Kaplan’s triphasic model encompasses desire, excitement and orgasm phases, each distinct in its physiology, pathology and therapies for dysfunction.

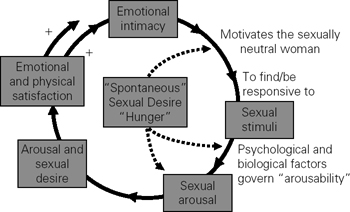

Rosemary Basson discussed the circular model of female sexual function (Figure 68.3). In this concept, the reaction to sexual stimuli is not spontaneous but rather represents a complex interaction of biology, psychology, sociocultural influences, and interpersonal relationships. This biopsychosocial model proposes that sexual response does not necessarily occur in a linear, automatic fashion but rather is dependent on several emotional, physical, and environmental components. The phases of sexual response can occur at overlapping or varying times. The motivation for sexual function may be from a variety of different facets including an innate desire, the need for intimacy or because the woman is genitally aroused. The goal of the sexual experience is personal and relationship satisfaction, and orgasmic release is not necessary. This novel model therefore implies that treating sexual dysfunction must address all mechanisms of sexual response, not solely the physical one.

Figure 68.3 Female sexual response cycle: Basson intimacy-based model. Adapted from Basson R. Female sexual response: the role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol 2001: 98(2): 350–353.

Recent research by Michael Sands and colleagues demonstrated that women demonstrate the Masters & Johnson model, the Kaplan model and the Basson Model. They may shift from one model to the next during a sexual experience or between experiences. Women with sexual complaints may more often identify with the Basson model of female sexual function.

Physiology of female sexual function

The physiology of the female sexual response does not solely involve the genital pelvic organs and the internal pelvic structures. The spinal and central nervous system are also major contributors to female sexual response as well as many areas of the brain, including the hippocampus, hypothalamus, limbic system, and medial preoptic area. Many neurotransmitters and secondary modulators have also been implicated in the response cycle. This includes the neuropeptides serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, opioids, nitric oxide, acetylcholine, and vasoactive intestinal peptide. Sex steroids are essential in the female genital response, and estradiol and testosterone have been clearly implicated in the normative functioning of the response cycle. Sex steroids are one of many components in the complex and multifaceted cycle, but they are one of its critical mediators. They translate stimulus-triggered neurologic impulses into physical responses, such as altered vascular blood flow.

Estrogens

Estrogens have a beneficial effect on sexual function. They can act centrally as well as in the periphery to increase blood flow to both the brain and genitals. The hypothalamus, one of the primary regulators of both mood and sexual function, contains many estrogen receptors. Estrogen increases vasoactive substances in the blood vessels. For example, estrogen is partially responsible for the increased nitric oxide in endothelial cells during arousal. Nitric oxide, in turn, contributes to the vasodilation that is so important to the sexual response. Estrogens may also enhance vibratory sense in the periphery. They facilitate neuronal growth and transmission. Estrogens are critically important to the health of the vaginal lining, not only the suppleness of the mucosa but also the normal vaginal acidic pH. These actions of estrogen can affect a woman’s sexual health.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree