Chapter 4 Female Reproductive Physiology

The Menstrual Cycle

The Menstrual Cycle

Each menstrual cycle represents a complex interaction among the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, ovaries, and endometrium. Cyclic changes in gonadotropins (peptide hormones) and steroid hormones induce functional as well as morphologic changes in the ovary, resulting in follicular maturation, ovulation, and corpus luteum formation. Similar changes at the level of the endometrium allow for successful implantation of the developing embryo or a physiologic shedding of the menstrual endometrium when an early pregnancy does not occur.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis

Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis

PITUITARY GLAND

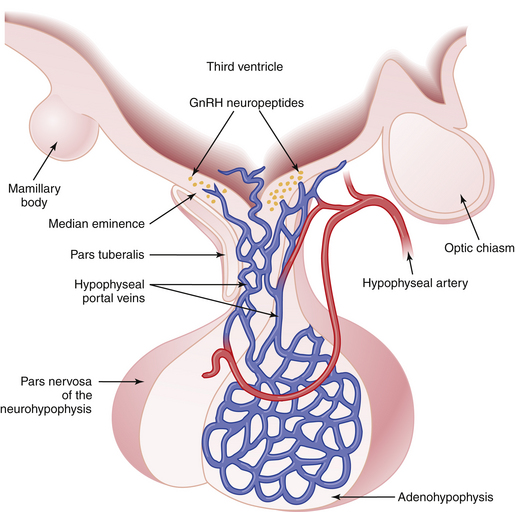

The pituitary gland lies below the hypothalamus at the base of the brain within a bony cavity (sella turcica) and is separated from the cranial cavity by a condensation of dura mater overlying the sella turcica (diaphragma sellae). The pituitary gland is divided into two major portions (Figure 4-1). The neurohypophysis, which consists of the posterior lobe (pars nervosa), the neural stalk (infundibulum), and the median eminence, is derived from neural tissue and is in direct continuity with the hypothalamus and central nervous system. The adenohypophysis, which consists of the pars distalis (anterior lobe), pars intermedia (intermediate lobe), and pars tuberalis—which surrounds the neural stalk—is derived from ectoderm.

Prolactin is secreted by lactotrophs. Unlike the case with other peptide hormones produced by the adenohypophysis, pituitary release of prolactin is under tonic inhibition by the hypothalamus. The half-life for circulating prolactin is about 20 to 30 minutes. In addition to its lactogenic effect, prolactin may directly or indirectly influence hypothalamic, pituitary, and ovarian functions in relation to the ovulatory cycle, particularly in the pathologic state of chronic hyperprolactinemia (see Chapter 32).

GONADOTROPIN SECRETORY PATTERNS

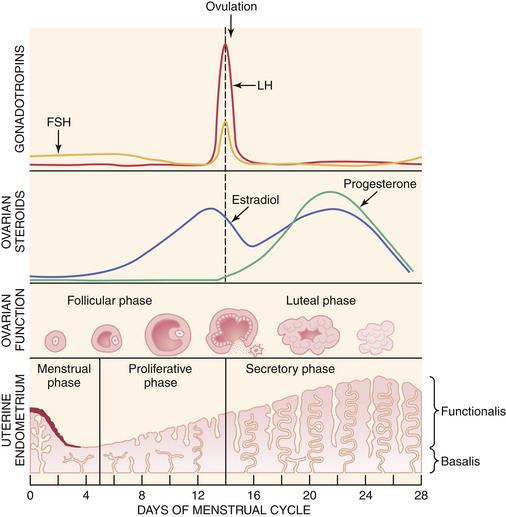

A normal ovulatory cycle can be divided into a follicular and a luteal phase (Figure 4-2). The follicular phase begins with the onset of menses and culminates in the preovulatory surge of LH. The luteal phase begins with the onset of the preovulatory LH surge and ends with the first day of menses.

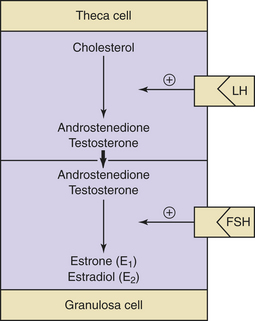

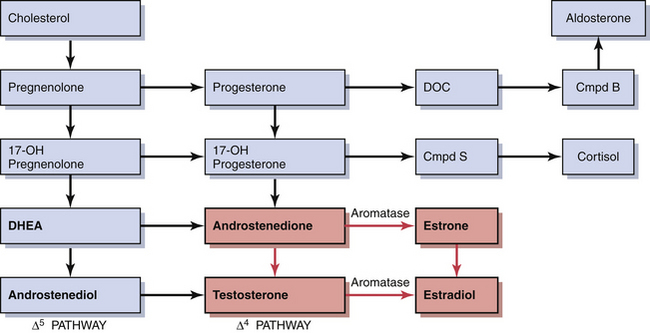

Decreasing levels of estradiol and progesterone from the regressing corpus luteum of the preceding cycle initiate an increase in FSH by a negative feedback mechanism, which stimulates follicular growth and estradiol secretion. A major characteristic of follicular growth and estradiol secretion is explained by the two-gonadotropin (LH and FSH), two-cell (theca cell and granulosa cell) theory of ovarian follicular development. According to this theory, there are separate cellular functions in the ovarian follicle wherein LH stimulates the theca cells to produce androgens (androstenedione and testosterone) and FSH then stimulates the granulosa cells to convert these androgens into estrogens (androstenedione to estrone and testosterone to estradiol), as depicted in Figure 4-3. Initially, at lower levels of estradiol, there is a negative feedback effect on the ready-release form of LH from the pool of gonadotropins in the pituitary gonadotrophs. As estradiol levels rise later in the follicular phase, there is a positive feedback on the release of storage gonadotropins, resulting in the LH surge and ovulation. The latter occurs 36 to 44 hours after the onset of this midcycle LH surge. With pharmacologic doses of progestins contained in contraceptive pills, there is a profound negative feedback effect on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) so that none of the gonadotropin pool (ready-release or storage) is released. Hence, ovulation is (generally) blocked (see Chapter 26).

During the luteal phase, both LH and FSH are significantly suppressed through the negative feedback effect of elevated circulating estradiol and progesterone. This inhibition persists until progesterone and estradiol levels decline near the end of the luteal phase as a result of corpus luteal regression, should pregnancy fail to occur. The net effect is a slight rise in serum FSH, which initiates new follicular growth for the next cycle. The duration of the corpus luteum’s functional regression is such that menstruation generally occurs 14 days after the LH surge in the absence of pregnancy.

HYPOTHALAMUS

GnRH is a decapeptide that is synthesized primarily in the arcuate nucleus. It is responsible for the synthesis and release of both LH and FSH. Because it usually causes the release of more LH than FSH, it is less commonly called LH-releasing hormone (LH-RH) or LH-releasing factor (LRF). Both FSH and LH appear to be present in two different forms within the pituitary gonadotrophs. One is a releasable form and the other a storage form. GnRH reaches the anterior pituitary through the hypophyseal portal vessels and stimulates the synthesis of both FSH and LH, which are stored within gonadotrophs. Subsequently, GnRH activates and transforms these molecules into releasable forms. GnRH can also induce immediate release of both LH and FSH into the circulation. Some recent research that found receptors for GnRH in other tissues including the ovary suggests that GnRH may have a direct effect on ovarian function as well.

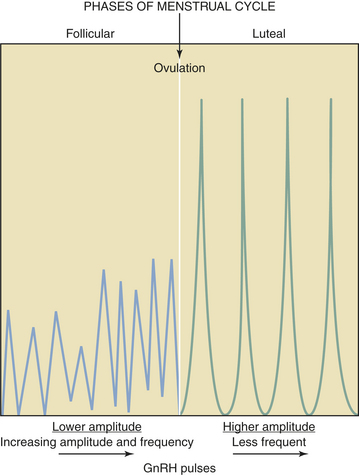

GnRH is secreted in a pulsatile fashion throughout the menstrual cycle as depicted in Figure 4-4. The frequency of GnRH release, as assessed indirectly by measurement of LH pulses, varies from about every 90 minutes in the early follicular phase to every 60 to 70 minutes in the immediate preovulatory period. During the luteal phase, pulse frequency decreases while pulse amplitude increases. A considerable variation among individuals has been identified.

The hypothalamus produces PIF, which exerts chronic inhibition of prolactin release from the lactotrophs. A number of pharmacologic agents (e.g., chlorpromazine) that affect dopaminergic mechanisms influence prolactin release. Dopamine itself is secreted by hypothalamic neurons into the hypophyseal portal vessels and inhibits prolactin release directly within the adenohypophysis. Based on these observations, it has been proposed that hypothalamic dopamine may be the major PIF. In addition to the regulation of prolactin release by PIF, the hypothalamus may also produce prolactin-releasing factors (PRFs) that can elicit large and rapid increases in prolactin release under certain conditions, such as breast stimulation during nursing. All PIFs and PRFs have not been clearly characterized biochemically as of 2008. TRH serves to stimulate prolactin release as well. This phenomenon may explain the association between primary hypothyroidism (with secondary TRH elevation) and hyperprolactinemia. The precursor protein for GnRH, called GnRH-associated peptide (GAP), has been identified to be both a potent inhibitor of prolactin secretion and an enhancer of gonadotropin release. These findings suggest that this GnRH-associated peptide may also be a physiologic PIF and could explain the inverse relationship between gonadotropin and prolactin secretions seen in many reproductive states.

Ovarian Cycle

Ovarian Cycle

ESTROGENS

During early follicular development, circulating estradiol levels are relatively low. About 1 week before ovulation, levels begin to increase, at first slowly, then rapidly. The conversion of testosterone to estradiol in the granulosa cell of the follicle occurs through an enzymatic process called aromatization and is depicted in Figure 4-3. The levels generally reach a maximum 1 day before the midcycle LH peak. After this peak and before ovulation, there is a marked and precipitous fall. During the luteal phase, estradiol rises to a maximum 5 to 7 days after ovulation and returns to baseline shortly before menstruation. Estrone secretion by the ovary is considerably less than secretion of estradiol but follows a similar pattern. Estrone is largely derived from the conversion of androstenedione through the action of the enzyme aromatase (Figure 4-5).