29 Fatigue

It’s like my legs weigh 100 pounds…1

You think about it, dwell on it and it makes it worse. So, part of it is mental and part of it is physical fatigue. You are not your normal self and you are just tired of everything that has happened.1

It’s like being wiped out …my body is just too tired for me to care.2

The direct effects of disease, side effects of treatment3 and medications prescribed to manage these contribute to fatigue in children with life-threatening illnesses. Infection, electrolyte imbalance, anemia, dehydration, malnutrition, endocrine dysfunction, and organ impairment are all factors. Psychological states including anxiety, fear, depression, and feelings of isolation and loneliness also influence the frequency and intensity of fatigue.4 Sleep disruption and poor sleep quality contribute to fatigue in children, particularly at the end of life. Sleep deprivation may worsen pain that exacerbates their tiredness. Children with cancer identify the hospital environment as a major contributing factor to fatigue because of the frequent disruptions in their sleep5 (Tables 29-1 and 29-2).

TABLE 29-1 Fatigue: Contributing Factors in Children with a Life-Threatening Illness

| Factor | Possible causes |

|---|---|

| Physical | |

| Psychological |

TABLE 29-2 Signs and Symptoms of Fatigue in Children

| Domain | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| Cognitive | |

| Physical | |

| Emotional |

Children’s Descriptions of Fatigue

Researchers exploring fatigue in seriously ill children confirm that perceptions of fatigue differ by developmental age.6–8 Younger children tend to emphasize the physical sensation of fatigue more than emotional aspects, and describe, for example, how watching television or reading comprise their main activities.

Adolescents tend to be more cognitively aware of the impact of fatigue on their lives, and often describe the symptom in terms of its effect on their lifestyle. They also highlight mental tiredness that alternates and at times merges with the physical sensation of fatigue.3,7–10 Teens describe activities that they can no longer perform and their inability to be with peers as significant changes brought on by fatigue. They are more aware of the relationship of the symptom to their overall illness or treatment. For example, adolescents can define when fatigue occurs in relation to their chemotherapy cycle.

Research on Fatigue in Children

Research on fatigue in children has focused primarily on children with rheumatologic disorders and cancer. Fatigue is characterized as a distressing, pervasive symptom with physical, mental, and emotional components characterized by a lack of energy.9,10

Children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) describe fatigue as a common symptom.11,12 In a study of 51 children with juvenile polyarticular arthritis, researchers found fatigue present along with pain and joint stiffness on more than 70% of days with significant variability in symptom levels.13 Researchers found a positive relationship between stress and mood and same-day variations in fatigue. A study of 15 children with SLE found fatigue to be a significant symptom in 67% of the children.14 These children also had reduced aerobic fitness compared to age and sex-matched reference norms. Fatigue was a significant symptom in a group of 52 children with Crohn’s disease.15 They had lower quality of life scores and significantly more fatigue compared with healthy controls.

Fatigue is the most frequent symptom experienced by children with cancer.9,10,16–20 In a survey of parents of children with cancer and their treating clinicians, 57% in each group reported fatigue as a frequent symptom.19 In a qualitative study of children receiving treatment for cancer, researchers generated a detailed description of fatigue: a core concept or energy, a core process or managing dwindling energy, and a typology of three types of fatigue: typical tiredness, treatment fatigue, and shutdown fatigue.18 Children with leukemia described fatigue, both disease and treatment-related, as having the greatest impact on their quality of life by altering participation in school, sports, and family activities. In a pilot study of nine school-age children with leukemia, diaries revealed evening fatigue and sleep disturbances21 during the maintenance phase of treatment. Fatigue was also the most frequently reported symptom in a group of 161 acute lymphocytic leukemia survivors,22 even many years after treatment.

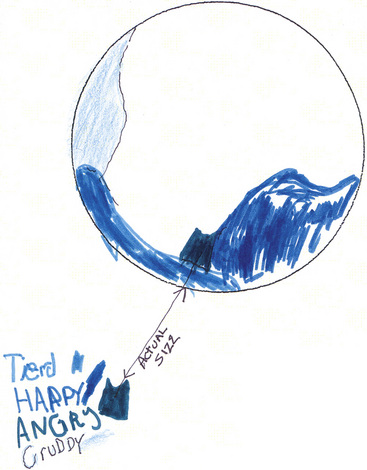

Studies have specifically addressed fatigue at the end of life within the childhood cancer population.23 A landmark study of symptoms and suffering at the end of life found that all 103 families surveyed report that their child had experienced fatigue during the last month of life.4 In a Swedish nationwide survey of 449 parents of children with cancer, 86% reported physical fatigue as the most frequently reported symptom that had moderate or high impact on their child’s well-being.24 A study of 65 parents of children who had died of cancer within the previous 6 to 10 months revealed that fatigue was one of the most frequently reported symptoms, along with pain, and changes in behavior, appearance, and breathing.25 Similar findings were found in 32 parents whose child had died within the past 3 years. They reported that the symptom burden was high during the palliative phase, with pain, poor appetite, and fatigue as the most frequently reported physical symptoms. Emotional symptoms included sadness, difficulty talking about feelings, and fear of being alone.26 Fatigue was a prevalent symptom in a group of 28 Japanese children at the end of life.27 In interviews with 30 parents whose children had received pediatric home hospice services, fatigue was one of the most frequently identified symptoms during the last week of their child’s life28 (Fig. 29-1).

Fig. 29-1 Parents need help with understanding the significant effects fatigue can have on their child.

A qualitative study exploring factors that influence quality of life in 49 children and adolescents with epilepsy found excessive fatigue as a barrier to academic and social pursuits. Participants described how intermittent or continuous fatigue made it difficult to think clearly and to fully participate in classroom learning.29

Fatigue may provide protection, as a shield from suffering, during the final stages of life; and treatment of fatigue at this stage of palliative care may be detrimental.30 When the death of a child is imminent, fatigue often intensifies and withdrawal from family and friends occurs as a result of diminished energy. Preparing the family for this eventuality may prevent their misinterpretation of tiredness as depression, or, even more painful, as a rejection of them (Fig. 29-2).

Assessment of Fatigue

Many patients and families assume that fatigue is an inevitable and untreatable side effect of disease or treatment and thus often do not report it as a symptom. Furthermore, until recently, standardized assessment of fatigue by clinicians has been oversimplified, as a yes or no checklist,6 or entirely absent.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend routine screening for fatigue as the sixth vital sign. Those older than 12 years of age should be screened using a simple numeric rating scale such as 0, no fatigue, to 10, worst fatigue. For children 7 to 12 years of age, a 1 to 5 point scale is recommended. For children aged 5 and 6 years the words tired or not tired should be used to determine fatigue. Once screened, patients should be evaluated for the seven treatable contributing factors to fatigue, which is informally referred to as the gang of seven: anemia, pain, sleep difficulties, nutrition issues, changes in activity patterns, emotional distress, and presence of co-morbidities.31–33 The health care team should assess for the onset and type of fatigue, aggravating or alleviating factors, and degree of interference with the child’s functioning.

Several research instruments are available to assess symptom clusters in children, including fatigue, although none was designed specifically for end of life. Once fatigue has been identified as a specific symptom it may be useful to use one of the validated and reliable pediatric fatigue scales, such as the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS), Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), or the Pediatric Quality of Life (PedsQL) scale.34

The Childhood Fatigue Scale (CFS) is a 14-item (four-point Likert scale) questionnaire that asks children (ages 7 to 12 years) about their tiredness during the previous week. The three subscales are: lack of energy, inability to function, and altered mood.8,35 Parent Fatigue Scale (PFS) is a 17-item inventory of parents’ perception of their child’s fatigue in the previous week. In addition to the three subscales on the children’s version, it also included a scale of altered sleep. The Fatigue Scale-Adolescent (FS-A) is a 14-item questionnaire that asks adolescents (ages 13 to 18 years), to evaluate their fatigue experience during the previous week. The child and parent scales are available in English and Spanish; the adolescent form in English only. The CFS, PFS, and FS-A are validated research instruments, easy to administer, and require limited time to complete in the clinical setting.8,35,36

The PedQL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale is an 18-item research instrument (ages 2 to 18) with three subscales: general fatigue, sleep-rest fatigue, and cognitive fatigue. The scale is self-administered for 8 to 18 year olds, interview-administered in 5 to 7 year olds and done by parent proxy for the youngest children. It is available in 22 languages.37,38 The Pediatric Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (Peds FACIT-F) is an 11-item scale for children with cancer that measures fatigue in the past 7 days. It is correlated with the Peds QL Multidimensional Fatigue Scale and is available in English and Spanish.35,39