CHAPTER 5 Family Context in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics

Children’s health and development are a family affair. Whether it involves keeping scheduled appointments for a child’s immunizations, managing feeding difficulties in a child with Down syndrome, or negotiating an adolescent’s desire for autonomy, the daily life of the family is integrally intertwined with the health and well-being of children and adolescents. Family-level factors such as direct and open communication and availability of support have been found to be associated with a host of child health outcomes, including infant mortality,1 lifetime hospitalizations,2 and the likelihood of developing posttraumatic stress symptoms after the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness.3 There are several ways to consider family contributions to children’s development.

First, families are responsible for providing food, shelter, and stability for children. At its most basic level, the provision of basic resources means that the family holds the key to children’s nutritional status and physical comfort. However, families do not always have complete control over available resources; parent’s educational backgrounds, their economic circumstances, and characteristics of the neighborhood also have influences on children’s health.4 Thus, a consideration of family influences on children’s health and development must also include the environments in which families live. Second, families are the holding place for children’s emotional development. Children learn to trust others and regulate their emotions in the safe surroundings of their home before venturing out to school and other social environments. For some children, this is a relatively positive experience, and they come to school well equipped to meet academic and social challenges. For other children, inconsistent and erratic experiences in the home often leave them ill equipped to interact with others, which thus places them at risk for school failure, behavioral problems, and strained peer relationships.5 In all cases, these experiences are mutually influential: Characteristics of the child influence the family, and the family influences the child’s development. Third, family members create practices and hold beliefs that often extend across generations and are influenced by culture. Family life is organized in such a way that it builds on past experiences, which results in predictable routines and imparting of values through recounting personal experience. Many families benefit from their heritages and can use them as guides in meeting the challenges of raising their children. For some families, however, personal histories of neglect, substance abuse, and parental psychopathology interfere with the constructive transfer of generational knowledge and can place children at risk for poor health and development.6–8

The empirical study of family influences on children’s development is complicated at best. Identifying who is in the family; whether to rely on direct observation of family interactions or parent’s report of family climate; how to resolve inconsistencies in reports by mother, father, child, and teacher about child behavior; and adaptation of techniques across cultures9 are just a few of the thorny issues in the scientific study of families. In addition, the changing demography of American families includes increasing numbers of children who are being raised by parents of different ethnic backgrounds, in single-parent households, or in multiple households.10 For the medical clinician, keeping track of all the layers of family life can seem like an overwhelming task, particularly in the short amount of time allocated for patient visits. Rather than ignore the apparent complexity of family life, in this chapter we offer some guidelines for the busy clinician to consider in his or her contact with children and their families. Because the importance of establishing partnerships with families is the cornerstone of pediatric practice,11 a greater understanding of how families operate is in order.

In the past there was a tradition in developmental studies to equate poor child outcomes directly with poor parenting. Such terms as “refrigerator mothers” were coined to suggest that parents (most notably mothers) with cold and harsh parenting techniques were the sole progenitors of their children’s ill health, mentally and physically.12 Childhood schizophrenia was thought to develop from rejecting and harsh parenting styles. Pediatric asthma was thought to arise from overcontrolling and smothering parenting styles.13 At the root of these notions was the assumption that parenting effects were always direct and unidimensional and that neither characteristics of the child nor the surrounding environment had much of an effect on development. Clearly, these notions are outdated because advances in behavior genetics suggest heritability quotients for such conditions as schizophrenia and that symptom severity in asthma is the result of complex interactions among environmental conditions, genetic factors, and family factors.14 The point is that parents do not directly cause their child’s poor health or maladaptive development; rather, children’s health and well-being are embedded in a family context that is subject to a variety of influences, some of which we outline in this chapter.

This chapter is structured in the following ways. First, we provide an overview of a theoretical framework that we believe can be of use for clinicians as they think about the complexities of family life. We first review the social-ecological model originally proposed by Bronfenbrenner.15 This theoretical model is useful in that it allows clinicians to consider not only how the child is situated in the family but also how the family is influenced by the neighborhood in which it lives, the schools that are available to the child, and the culture with which the family most closely identifies. Second, we also consider that children and families change. They do so as part of a process whereby families influence the growth and development of their children and the characteristics of the child also influence how the family functions. This process has been labeled transactional, which suggests that development is characterized by a series of active exchanges between parents and children and that both child and parent contribute to a child’s condition at any given point in time. Thus, we also outline the transactional model as originally proposed by Sameroff and colleagues.16,17 Integrally linked to the social-ecological and transactional perspectives is the role that multiple risk factors play in development. Optimal and poor outcomes are rarely the result of a single factor; rather, the multiple influences of culture, economic resources, family support, and child characteristics cumulatively affect development over time. Thus, we consider the compound effect of environmental risks.

After this strong theoretical grounding in the social-ecological and transactional models and family systems principles, we review some of the literature that illustrates family effects on child health and well-being. Specifically, we examine family factors that promote adjustment in children with a chronic illness, parenting variables that can reduce the risks associated with poverty, and how cultural beliefs and practices enacted in the family context can influence child health and well-being. We conclude with recommendations for clinicians in their clinical decision-making process with families, as well as policy makers responsible for the health and well-being of children. Throughout the chapter, we use vignettes to illustrate our points and to elucidate these complex concepts. Consider the following scenario:

SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL MODEL

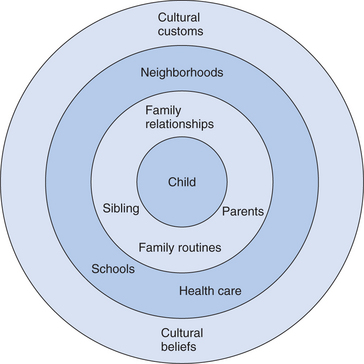

In this brief scenario, we have several elements of Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological model (Fig. 5-1). The child is at the center of the model. The child’s development is proposed to be influenced by the persons most immediately around him. In this case, Jamie’s development is affected primarily by his mother and siblings. The child’s developmental status is influenced by how responsive his mother is to his needs, as well as by the support and opportunities provided by interactions with his siblings. However, the degree to which the mother is emotionally available to interact with the child in a warm and responsive way may be influenced by her relationship with her ex-husband. We know, for example, that marital conflict can have detrimental effects on children’s development by disrupting effective parenting styles and setting the stage for poor emotion regulation by children.18 Thus, the environment closest to the child’s daily experiences may have a direct influence on his development through exposure to supportive and warm interactions or through a home environment that is characterized by conflict and disruptions. These interactions do not operate in isolation but are influenced by the next level of Bronfenbrenner’s model.

Once we move out of the immediate confines of the family home, we note that there are other influences on child development that can have profound effects on the development of children. This is the level most commonly encountered by pediatricians, inasmuch as how families interact with health care teams also affects how children cope with chronic illnesses.19 In the preceding example, the likelihood that Jamie will develop to his fullest potential will depend not only on his family’s best intentions but also on their ability to gain access to early childhood programs in their neighborhood. Transporting a 4-year-old child five blocks to the home of a babysitter, who must in turn put him on a bus for a long ride for a 3-hour early intervention program, represents a daily challenge. Even under the most optimal home conditions, this would be an added strain to the system that may compromise the child’s developmental progress. Thus, the degree to which the resources available outside the home support, or derail, family investments can have a direct influence on child developmental outcomes.

There is a third level to the social-ecological model that can also influence child development. This layer of the social environment includes such factors as culture, social class, religion, and law. In the preceding example, the legal system has an indirect influence in that public laws guarantee access to public education for all children, regardless of developmental condition. However, as noted previously, gaining access to available education programs can be tempered by resources available in the neighborhood. Culture and religion can also influence child development indirectly. In the case of Jamie, we noted that his mother held strong religious beliefs. Religious beliefs may affect how parents cope with the daily care of children with special needs, so that practices endorsed by mandated programs must also coincide with deeply held doctrines.20

Transactional Model of Development

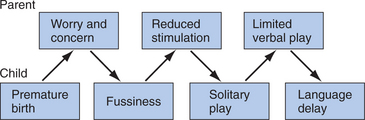

Was the cause of Joanna’s language delay her prematurity and low birth weight? It is known that premature children are at greater risk for developing language delays than are full-term infants.21 Or was the cause of her language delay her fussiness and difficult temperament? Or being less favored than her older brother? Or being left alone? From a transactional perspective, all of these features may come into play when a child’s developmental outcome at any given point in time is considered. In this case, the parents have reasonable concern about their vulnerable infant. Rather than being able to bring their infant directly home, they had to wait and ponder their daughter’s health. Seeking information through the Internet or hospital personnel, they discovered that premature infants are sensitive to light and sound. In this case, Joanna’s fussiness was interpreted by her parents as further indication of her need to have reduced exposure to stimulation, and thus they put her down in the crib frequently. There were fewer opportunities for social interaction and verbal play. This was interpreted as a temperamental difference or perhaps a gender difference in comparison to her brother. Without adequate opportunities for verbal play, Joanna did not develop an age-appropriate vocabulary; thus, her overall language abilities were delayed. This process is outlined in Figure 5-2.

The transactional model as proposed by Sameroff and colleagues16,17,22 emphasizes the mutual effects of parent and caregiver, embedded and regulated by cultural mores. In this model, child outcome is predictable by neither the state of the child alone nor the environment in which he or she is being raised. Rather, it is a result of a series of transactions that evolve over time, with the child responding to and altering the environment. For pediatricians, this model is important because it gives due recognition to the child’s effect on the environment, as well as to the environment’s effect on the child. Pediatricians are frequently faced with situations in which parents feel ill equipped to deal with the challenges of parenting, assuming that childrearing is a one-dimensional task that should conform to a set of prescribed principles easily accessible through a book or the Internet. Typically, this naive view is quickly cast aside with the birth of a second child and parents realize that a one-size-fits-all approach to parenting is rarely successful. Thus, to be able to predict how families influence children, the investigator must also ask how children influence families and how this process develops over time. In addition to recognizing that parents and children mutually influence each other, the transactional model is also important in highlighting the multiply determined nature of risk in family environments.

Multiply Determined Nature of Risk in Family Environments

ADOLESCENT ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND PSYCHOLOGICAL ADJUSTMENT

In a large study of adolescents in Philadelphia, the relation between exposure to a variety of risk factors and both academic achievement and psychological adjustment was examined.5 Using an ecological framework, the researchers identified six domains of risk: family process, parent characteristics, family structure, management of community (e.g., social networks), peers, and community (e.g., neighborhood). Adolescents were assigned risk scores for each domain. Lack of autonomy, low-level parent education, single marital status of parents, lack of informal networks, few prosocial peers, and low census tract socioeconomic status are examples of high risk in each of the domains. Increasing numbers of risk factors was associated with large declines in academic performance and psychological adjustment. Using an odds-ratio analysis, the authors compared the likelihood of poor outcomes in high-risk environments with those in low-risk environments. For academic performance, they found that a poor outcome increased from 7% in the low-risk group (three or fewer risk factors) to 45% in the high-risk group (eight or more risk factors)—an odds ratio of 6.7 to 1.

Two factors that are repeatedly identified as contributors to children’s well-being are parental income and marital status. Research on multiple risk factors highlights, in part, how income and marital status are embedded in larger social ecologies that act in concert with other risk and protective factors. This is important in consideration of family effects on child health and development, inasmuch as marital status and economic stability are commonly viewed as structural family variables essential for children’s well-being. Whether a parent is married or holds a prestigious job is not the litmus test for positive family influence on child outcomes. In isolation, these structural variables are not informative about the larger social environment in which the child is being raised or the nature of family process in the home. For example, it is known that there are many types of single-parent families and that children of divorced parents do not necessarily develop mental health problems.23

How children fare during and after divorce is a topic of considerable concern to pediatricians. During the 1990s, more than 1 million children were involved in divorce every year.24 In a meta-analysis of 67 studies conducted between 1990 and 1999, Amato25 found that children of divorced parents scored significantly lower than did children with married parents on measures related to academic achievement, conduct, psychological adjustment, self-concept, and social relations. These differences were less pronounced in African-American children than in white children.26 Marital discord appears to play an important role in how children are affected by parental divorce. Not only the presence or absence of discord but also how conflict unfolds during the dissolution of the marital relationship is important. When children have not been exposed to discord before the divorce, there are more long-term difficulties in adjustment, which suggests that there is an increase in conflict and stress after the divorce.25 In contrast, when there are relatively high levels of conflict before the divorce, dissolution of the marriage can actually be a relief for the child, and there are fewer long-term effects on child adjustment. Thus, what results in poor adjustment in children is not divorce per se but exposure to marital conflict. Experimental studies have also documented that children’s exposure to unresolved marital conflict, in particular, is more likely to result in emotional and behavioral disturbances than are marital disagreements that children witness as reaching some resolution.18

MULTIPLE RISK FACTORS AND POVERTY

Children growing up in poverty are disproportionately affected by chronic health conditions, including asthma, obesity, and diabetes. Children growing up in poverty also show early signs of allostatic load and higher resting blood pressure, which suggests that they are at increased risk for developing other serious chronic health conditions.27 In 2003, the poverty rate was highest for younger children; 20% of children between birth and the age of 5 years of age were being raised in households below the poverty line.28 There are concerns that children exposed to poverty over long periods may be at increased risks for poor physical and social-emotional outcomes. Limited economic resources can have crushing effects on family life, not only through its effects on the provision of basic needs but also by its effects on relationships and parenting. For example, in studies of rural farm families in Iowa, it was found that the downward turn of economic circumstances preceded marital distress and led to increases in hostile and coercive interactions between parents and adolescents.29 As noted previously, the compound effects of risk may influence child outcome; a similar picture holds true with regard to the effects of poverty on child health and well-being.

Evans30 considered the physical and mental health of children raised in poor rural communities and the multiple environmental risks they were exposed to, including crowding, noise, housing problems, family separation, family turmoil, violence, single-parent status, and parent education level. In accordance with the previous reports on multiple risk factors in less economically disadvantaged families, increasing numbers of risk factors were associated with more child psychological distress and feelings of less self-worth. Furthermore, children exposed to more environmental risk factors also evidenced higher systolic blood pressure and elevated neuroendocrine stress reactivity. As Evans stated, “As childhood exposure to cumulative risk increased, overall wear and tear on the body was elevated.” (p. 928).

Risk conditions are often compounded in nature and difficult to unravel. For example, the effects of family poverty on children’s health depend on how long the poverty lasts and the child’s age when the family is poor.31 Single-parent status also cannot be viewed in isolation, because the number of adults in the household has been identified as a marker of socioeconomic status known to be associated with some child outcomes.32 Perhaps one of the multiple-risk contexts that is most difficult to disentangle is that of the overlapping effects of economic conditions and ethnic background. In many empirically based studies of family effects on child development, poverty is confounded with minority status.33 One exception is a study employing the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Bradley and colleagues examined nearly 30,000 home observations of young children diverse in economic and ethnic backgrounds.34 Because of the relatively large sample size, the researchers were able to distinguish between poor and nonpoor European-American, African-American, and Hispanic-American families. In general, they found that poverty accounted for most, but not all, of the differences between the groups with regard to less stimulating home environments (availability of books, having parents read to the child, parent responsiveness). There were some differences, however, that were attributed to ethnic background when poverty status was controlled. For example, European-American mothers were more likely to display overt physical affection during the home observation than were African-American mothers. There were no ethnic group differences in the likelihood that mothers would talk to their infants or answer questions prompted by their elementary school–aged children. Thus, the distinguishing characteristics most often associated with poor outcomes for children, such as the lack of enriching home environments, were more closely associated with low income status than with ethnic background. Further efforts are warranted to separate the effects of poverty from the influence of ethnicity on child outcomes. The long-term effects of coping with discrimination may also affect parenting practices, particularly because these practices are evaluated by researchers within the dominant culture.35 In this regard, it is also important to be cognizant of factors, such as race and economic background of the observer, that can influence evaluations of family process. We return to this point when we discuss family assessment.

FAMILIES AS ORGANIZED SYSTEMS

This is not an unlikely scenario that on the surface appears fairly mundane but may include several elements of healthy family functioning. Families are charged with a host of tasks to insure the health and well-being of their children. Families are responsible for providing structure and care in at least six domains: (1) physical development and health; (2) emotional development and well-being; (3) social development; (4) cognitive development; (5) moral and spiritual development; and (6) cultural and aesthetic development.36 Each of these tasks can be considered as building on the other in a hierarchical manner; however, in day-to-day family life, they often overlap and are not clearly differentiated. In the example just provided, while the family is grabbing a quick breakfast before heading out the door for the day (and, it is hoped, fulfilling the nutritional needs of the children), they are also attending to their cultural and aesthetic development through the arrangement of after-school lessons. Families structure care and meet the developmental needs of their children through organized daily practices, as well as through beliefs that they carry about relationships. We now examine how daily practices, as reflected in family routines, and beliefs, as reflected in family narratives, are related to the health and well-being of developing children.

Family Routines and Healthy Development

In accordance with our focus on the multiply determined nature of child development, children’s health is also considered part of a larger system of family functioning. When we think about family health, we think about what the family, as a group, must do to maintain the well-being of all its members, including establishing waking and sleeping cycles, establishing eating habits, responding to acute illness, coping with chronic illness, preventing disease, and communicating with health professionals. These activities, or practices, are often folded into the family’s daily routines. Pediatricians are poignantly aware that for some chronic health conditions, family involvement in daily care is essential to good health but, at the same time, these management behaviors can be “tedious, repetitive, and invasive” (Fisher and Weihs,37 p. 562). This repetitive nature of management activities sets the stage for creating routines that provide predictability and order to family life. Conversely, the repetitive demands associated with good health care may also disrupt routines already in place and threaten family stability. We first define what we mean by family routines and then examine their relation to child health and well-being.

DEFINING ROUTINES

There is a personalized nature to family routines that makes it somewhat difficult to provide a standard definition. What may be a routine for one family may be absent in another. For example, some families hold very high expectations for when everyone is to be home for dinner and have set rules for the expression of emotional displays, whereas other families have a more laissez faire attitude toward mealtime attendance and rarely remark when someone makes an angry outburst at the table.38 Family routines tend to include some form of instrumental communication so that tasks get done, involve a momentary time commitment, and are repeated over time.39 In terms of normative development, family routines such as dinnertime, weekend activities, and annual celebrations (e.g., birthday celebrations) tend to become more organized and predictable after the early stages of parenting an infant and into preschool and elementary school years.40 The regularity of family routine events such as mealtimes have been found to be associated with reduced risk taking and good mental health in adolescents.41,42 The sense of belonging created during these gatherings has been found to be associated with self-esteem and relational well-being in adolescents and young adults.40,43

HABITS

Habits are repetitive behaviors that individuals perform, often without conscious thought. Behavioral habits are automatic and typically involve a restricted range of behaviors. For example, some children may have developed a habit of snacking while sitting in front of the television set after school. A routine, on the other hand, involves a sequence of steps that are highly ordered.44 For example, a child’s morning routine may include a sequence of having breakfast, brushing teeth, checking the contents of a backpack, and playing catch with the dog before going to school. Healthy (or unhealthy) habits are often embedded in routines. Being in the habit of eating a nutritionally balanced meal may rely, in part, on shopping and cooking routines. For the most part, habits are rarely thought about, and pediatricians must ask repeatedly about parents’ and children’s daily routines to gather accurate information about healthy and unhealthy habits. It is not sufficient to ask whether a child eats a healthy diet, but it may be important to consider whether the diet is offered as part of a regularly organized routine.

Organized family routines may be part of good nutritional habits. For example, parents’ report of the importance of family routines has been found to be associated with children’s milk intake and likelihood of taking vitamins in low-income rural families.45 During the preschool and early school years, if mealtime routines are rushed and interactions are marked by discouragements and conflict, then children are at greater risk for developing obesity.46,47 Furthermore, if mealtime routines are regularly accompanied by television viewing rather than conversation, children consume 5% more of their calories from pizza, salty snacks, and soda and 5% less of their energy intake from fruits, vegetables, and juices than children from families with little or no television use during mealtimes.48 Qualitative studies have noted that individual members can disrupt diabetes management by routinely eating late, regularly serving desserts, and making daily shopping trips to grocery stores that have few choices in the way of fresh fruits and vegetables.49 Grocery shopping routines may also be affected by larger ecologies as lower income neighborhoods are often noted for grocery stores that do not have a full array of fresh produce. Thus, family routines may contribute to children’s health through establishing good nutritional habits and providing regular rather than erratic opportunities to be fed.

ADHERENCE

Adherence to pediatric medical regimens is notoriously poor. According to most surveys, families fail to follow medical advice more than half the time.50 It is unlikely that all cases of medical nonadherence are caused by lack of knowledge or a failure to fully understand doctor’s orders.51 Patients often remark that they fail to follow prescribed orders not because they want to but because they just could not find the time or because other responsibilities got in the way. There is no question that family life is busy and there are multiple demands on everyone’s time. Whether it is juggling home and work, squeezing in one more extracurricular activity, or just trying to get everyone fed during the week, the addition of a medical regimen to family responsibilities can seem overwhelming. One way that some families can adapt to the challenges of medical management is through the organization of their daily routines.

Many treatment guidelines for chronic health conditions suggest folding disease management into daily routines. The management of pediatric asthma is one such condition. Current practice guidelines14 emphasize the importance of daily and regular monitoring of asthma symptoms and detailed action plans in the event of an attack. Many of the recommendations are framed as part of the family’s daily or weekly routines such as vacuuming the house once a week, monthly cleaning of duct systems, and daily monitoring of peak flows. Accordingly, asthma management becomes part of ongoing family life, and families who are more capable of the organization of family routines are expected to have more effective management strategies.

In a survey of 133 families with a child who had asthma, it was found that parents who identified regular routines associated with taking and filling prescriptions had children who took their medications on a more regular basis, both according to parents’ report and according to computerized readings taken on the children’s inhalers.52 Furthermore, when there were regular medication routines in the home, parents had less trouble reminding their children to take their medications, and overall their children rarely or never forgot to take their medications. Because nonadherence to pediatric regimens is quite high53 and parents find themselves in the role of perpetual nagger, the establishment of regular routines may be one way to alleviate distress and promote health in children with chronic conditions. Future research appears warranted in order to consider whether interventions aimed at structuring family routines may positively affect disease management and increase medical adherence.

PARENTAL COMPETENCE

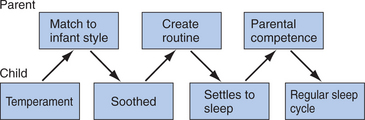

Family routines may also be important in promoting parental competence and establishing caregiving practices associated with children’s health and well-being. There is some evidence to suggest that experience with childcare routines before the birth of the first child is positively related to feelings of parental competence.54 However, in addition to parent skill set, the child contributes to these feelings, as was identified in the transactional model. Infant rhythmicity (e.g., regularity with which infants go to sleep at night) has been found to be associated with regularity of family routines, which, in turn, were associated with parental competence.55 The relation between caregiving competence and family routines during the early stages of parenting is probably the result of a series of transactions. When there is a good match between infant and parent behavioral style, it may be easier to engage the child in family routines. Routines become relatively stable, and the infant is easier to soothe, more amenable to scheduled naps, and less likely to wake in the night. This predictability, in turn, may reduce parental uncertainty and concern and increase feelings of competence. As parents engage in more rewarding daily caregiving activities, they become more confident in their abilities, and the routines themselves become more familiar and easier to carry out; for example, the difference between diapering an infant for the first versus the thousandth time is remarkable. The transactional process of one evolving caregiving routine is presented in Figure 5-3.

BELONGING VERSUS BURDEN

As the family practices its routines over time, individual members come to expect certain events to happen on a regular basis and form memories about these collective gatherings. For some, family is seen as a group that is a source of support, and repeat gatherings are eagerly anticipated. For others, family is seen as a group unworthy of trust, and collective gatherings are avoided. We have found that families who ascribe positive meaning to repeated routine gatherings such as dinnertime, weekends, and special celebrations feel more connected as a group and consider these events as special times rather than times to be endured.39 These feelings of belonging created during family routine gatherings are also associated with the health and well-being of children and adolescents. For example, children with chronic health conditions who report more connections during their family routines are less likely to report anxiety-related symptoms such as worry and somatic complaints.56 Furthermore, adolescents raised in caregiving environments with high-risk characteristics such as parental alcoholism are less likely to develop substance abuse problems and mental health problems when they report a sense of belonging created during family routines.57

In contrast to eagerly anticipating family events are feelings of being burdened and overwhelmed by the daily demands of family life. Feelings of burden can be particularly poignant in caring for a child with a chronic illness. Chronic illnesses can affect family life in notable ways, including added financial burden,58 and can place strains on marital relationships.59

Burden of care specifically associated with daily routine management may be related to quality of life for caregiver and child. In the previously mentioned study of 133 families with asthma, an element of daily care labeled routine burden was identified.52 Routine burden was defined as daily care seen as a chore with little emotional investment in caring for the child with the chronic illness. For both the caregiver and the child, when daily routines were considered more of a burden, quality of life was compromised. Caregivers reported that they were more emotionally bothered by their child’s health condition and their daily activities were affected more when there was more routine burden. Likewise, children reported that they were bothered more by their health symptoms, worried more, and were more frustrated by their health symptoms when their caregivers reported more routine burden. Routine burden was associated with functional disease severity, so that parents of children who required more care also believed that management was a chore. However, even when investigators controlled for disease severity, parents who perceived asthma care as a burden also reported poorer quality of life, as did their children.

CHAOS

It is possible to consider that the absence of routines is expressed as chaos. Chaotic home environments can be characterized by unpredictability, overcrowding, and noisy conditions.60 These types of conditions are more likely to exist in low-income environments and in neighborhoods perceived as dangerous and isolated. Research has indicated that the presence of chaos in the home, rather than poverty alone, mediates the effects of poverty on childhood psychological distress.61 Furthermore, children raised in chaotic environments have more difficulties reading social cues, and their parents use less effective discipline strategies.62 Thus, children exposed to chaotic environments lacking in predictable routines may also be exposed to other risks known to be associated with poor outcomes such as poverty, overcrowding, and dangerous neighborhoods. Again, we emphasize that family factors rarely, if ever, operate in isolation.

SUMMARY

One way to consider families as organized systems is to examine their daily practices. Families are faced with multiple challenges in keeping the group together; they must balance the needs of individuals who differ in age and personality, connect the family to institutions outside the home, and provide some regularity and predictability to daily life. At its most basic level, individuals create daily habits that become parts of the family’s routine practices. These routines are associated with family health in areas such as nutrition, establishment of wake and sleep cycles, and exercise. The establishment and maintenance of routines may enhance adherence to medical regimens. Families who have had experience generating such practices should be better equipped to fold disease management into their daily lives. We return to this point when we discuss models of family intervention useful for pediatricians. The repetition of family routines over time may lead to feelings of efficacy and competence, particularly for parents. Success in caregiving routines may reduce the stresses and uncertainties that accompany being a new parent, which, in turn, may affect children’s well-being in a transactional manner by increasing parents’ sense of personal efficacy. Parents who feel more efficacious are also more likely to interact in positive and sensitive ways that promote child well-being.63

When family routines are repeated over time and family gatherings are anticipated as welcomed events, individual members create memories that include a sense of belonging. This connectedness to the family, as a group, is associated with general health and relational well-being for adolescents and young adults and may reduce some of the mental health risks associated with chronic illness. The converse is also true: If the repetition of family routines over time results in feelings of dread and distance from the group, then there are concomitant effects on the health and well-being of child and parent.