Renal failure

Since the kidney is responsible for the elimination of most drugs from the body (either before or after inactivation by the liver), an assessment of how well the kidney is functioning is an essential part of the daily care of any patient on medication. Kidney function can fluctuate rapidly in the neonatal period so it should be assessed at the time treatment is first prescribed and monitored daily.

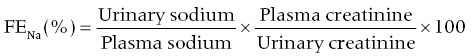

Deterioration occurs because blood flow has decreased (pre-renal failure), because the kidney has suffered damage (intrinsic renal failure) or because urine flow has been obstructed (post-renal failure) – although both pre- and post-renal failure can also cause secondary kidney damage. Clinical examination, and knowledge of the other problems involved, will often suggest where the problem lies. In babies with normal renal function, sodium excretion is driven by intake, and therefore varies widely. The proportion filtered that appears in urine (fractional excretion, FENa) is equally variable.

Check whether all concentrations are expressed in the same units. Babies with pre-renal failure (who are typically oliguric and hypotensive) conserve sodium avidly under the control of aldosterone. They will have a FENa ≤ 3% (<5% when <32 weeks gestation and <2 weeks old) regardless of the intake and the plasma level, except after a large dose of furosemide. Babies with established failure have a high FENa excretion because reabsorption is impaired by tubular damage.

Weigh all ill babies at least once a day because weight change is a sensitive index of fluid balance. Babies normally lose weight for 3–5 days after birth as they shed extracellular fluid (including sodium) following the loss of the placenta through which they were ‘dialysed’ before birth. Weight gain at this time is either a sign of excessive fluid intake or of early renal failure. Even healthy growing babies gain weight only by 2% a day. Gain in excess of this is a very useful sign of kidney failure. Urine output will vary with fluid intake, but any baby putting out less than 1 ml/kg of urine per hour is almost certainly in failure. A rising plasma creatinine or a level above 88 μmol/l (>1 mg%) in a baby more than 10 days old suggests some degree of renal failure, but the plasma level should never be relied on to identify failure because it rises six times more slowly after any insult than it does in an older child or adult.

Early diagnosis is vital because the elimination of some commonly used but potentially toxic drugs, such as gentamicin, is entirely dependent on excretion in the urine. Furthermore, most acute renal failure in the neonatal period is, at least initially, pre-renal in origin – often as a result of sepsis, intrapartum stress or respiratory difficulty – and early diagnosis makes early treatment possible. Trouble can often be anticipated. The later the problem is recognised, the more difficult management becomes.

The frequency with which it is necessary to rescue a baby from metabolic chaos by dialysis is inversely related to the promptness with which such a threat is recognised. A strategy for the conservative management of hyperkalaemia in p. 464 (and p. 420).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree