Chapter 33 Eye Pain and Discharge (Case 5)

Patient Care

Clinical Thinking

• Evaluate for trauma such as globe rupture or penetrating foreign body, both ophthalmologic emergencies that mandate immediate consultation. Delay in definitive diagnosis and treatment could result in permanent impairment of vision or blindness.

• A child with suspected orbital cellulitis requires immediate evaluation for extension of infection to the central nervous system (CNS).

History

• Has there been any contact with children with similar symptoms? Is there fever or other systemic signs of illness?

Physical Examination

• Evaluate for meningeal signs; if the eye pain is due to orbital cellulitis, there could be extension to the brain.

• Is there decreased visual acuity, impaired extraocular mobility, impaired pupillary response, or proptosis?

Tests for Consideration

• Fluorescein examination: Of the sclera for abrasions, or dendritic or ulcerative lesions consistent with keratitis $110

• Blood culture: If febrile and/or toxic appearing with concern for preseptal or orbital cellulitis $152

Clinical Entities: Medical Knowledge

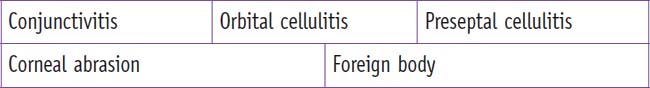

| Conjunctivitis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Two thirds of pediatric conjunctivitis (“pink eye”) is due to bacterial organisms, with viral infections accounting for the rest. Nontypable Hemophilus influenzae (HiNT) are the most common bacterial isolates, followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Moraxella catarrhalis. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis occur rarely in neonates who have received prophylaxis. Adenovirus is the most common viral etiology. Enteroviruses cause epidemics of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. Infectious agents are usually inoculated by contaminated hands or aerosolized droplets. |

| TP | There is conjunctival erythema, discharge, and mild discomfort, and possible photophobia or chemosis (conjunctival edema). Bacterial conjunctivitis is typically acute in onset, with mucopurulent exudate. The onset of a viral infection is typically unilateral, often subacute with clear discharge, but either bacterial or viral infections may be unilateral or bilateral. There may also be otitis media in infants and toddlers. |

| Dx | The diagnosis is usually clinical—significant injection of the palpebral conjunctiva helps to distinguish conjunctivitis from other entities. Infants and toddlers should be checked for otitis media. Cultures may be indicated with suboptimal response to therapy. Cultures (requiring specialized medium/collection) are warranted in neonates if chlamydia, gonorrhea, or herpes simplex virus is suspected, along with evaluation for systemic infection. |

| Tx | Bacterial conjunctivitis is self-limiting but responds faster with topical ophthalmic antibiotics such as polymyxin B/trimethoprim. Quinolone drops are effective but more expensive and reserved for difficult-to-treat cases. Drops are easier to instill and better tolerated than ointments. For conjunctivitis-otitis, oral antibiotics alone are generally adequate. Caution patients to avoid letting the tip of the bottle contact the conjunctiva and contaminate topical medications. |

| Practically speaking, the difficulty of distinguishing viral from bacterial conjunctivitis in addition to school/day care policies prohibiting return until “on treatment,” results in routine treatment of presumed viral conjunctivitis with topical antibiotics. Children with active discharge and symptoms should avoid school until clear, given the contagiousness of adenovirus. If symptoms worsen or fail to improve, a slit-lamp examination should be considered. If neonatal chlamydia is suspected, oral or intravenous erythromycin is required to prevent pneumonia. Neonatal gonococcal ophthalmias is treated with parenteral antibiotics. See Nelson Essentials 119. | |

| Orbital Cellulitis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Orbital cellulitis most often results from extension of ipsilateral sinusitis causing subperiosteal abscess or phlegmon and can involve inflammation of all tissues posterior to the orbital septum. The most common organisms are those found in acute and chronic sinusitis: pneumococcus, HiNT, M. catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, and respiratory tract anaerobes. |

| TP | Classically, there is prodrome of upper respiratory infection (URI), followed by sudden onset of unilateral eyelid edema and erythema, with complaints of eye pain, especially with eye movement. Fever is common, and the child may appear quite ill. There may be proptosis, decreased visual acuity, diplopia, abnormal pupillary reflexes, and impaired extraocular muscle movement. These findings may be difficult to ascertain on examination due to patient anxiety and lid swelling with inability to open the eye. |

| Dx | History and physical examination findings will prompt a computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbits to confirm the diagnosis and typical preexisting sinusitis. White blood cell (WBC) count and acute phase reactants are typically elevated. Blood cultures are usually negative. |

| Tx | This is an ophthalmologic emergency, and intravenous antibiotics such as ampicillin/sulbactam are empirically administered. Clindamycin is used if methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is a concern. Otolaryngology and ophthalmology are consulted for consideration of surgical intervention. Surgery is indicated for abscess drainage, significant impairment of visual acuity, or worsening of clinical symptoms on intravenous antibiotics. Following clinical improvement, therapy is changed to a comparable oral antibiotic with close outpatient follow-up. If a blood or surgical culture yields an organism, antibiotic coverage may be altered accordingly. Duration of therapy is individualized based on severity of presentation, the organism, and overall response to treatment. See Nelson Essentials 104 and 119. |

| Preseptal Cellulitis | |

|---|---|

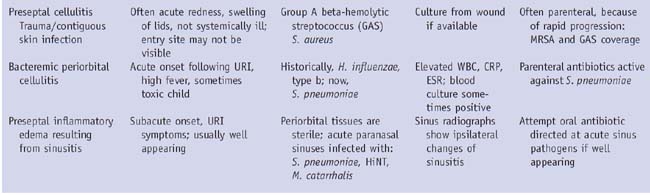

| Pϕ | Preseptal or periorbital cellulitis is infection of the eyelid and surrounding soft tissues, commonly due to contiguous skin infection or break in the integrity of the skin. It can extend to, but not past, the orbital septum. Before H. influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine licensure, the cause was usually hematogenous spread of typable H. influenzae. In ipsilateral acute sinusitis, there may be sterile inflammatory changes from venous stasis in the preseptal area. These conditions are always unilateral. There is no paralysis of extraocular movement or proptosis with a preseptal process. It may be difficult to distinguish orbital from periorbital cellulitis on examination, but they have distinctly different mechanisms and microbiology. |

| TP | See Table 33-1. |

| Dx | Physical examination can be challenging and inconclusive because children are likely to be uncooperative, and edema may prevent adequate assessment of extraocular eye movements. There is significant likelihood that CT will be required. |

| Tx | See Table 33-1. See Nelson Essentials 104 and 119. |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree