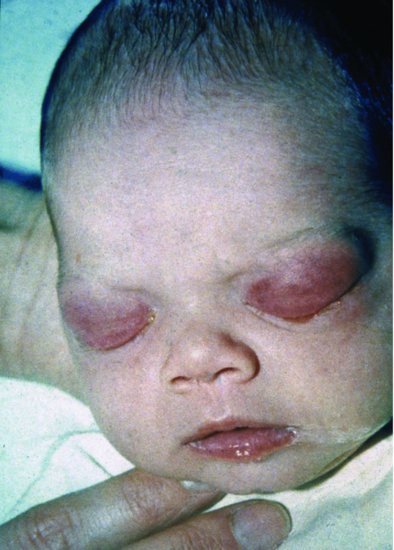

Chlamydial conjunctivitis (sometimes called inclusion conjunctivitis of the newborn) usually presents at 5–14 days, but intrauterine infection can result in earlier presentation.14 The severity can vary from mild conjunctival injection with minimal discharge to severe purulent conjunctivitis with chemosis and eyelid oedema, indistinguishable clinically from gonococcal conjunctivitis (Figure 12.2).14 Inflammatory exudate can adhere to the conjunctiva and cause a pseudo-membrane. Acute corneal involvement is very rarely described. In severe chronic infection, neovascularization of the cornea can result in pannus formation (corneal invasion by small blood vessels) and sight-threatening scarring as occurs in trachoma.14

Figure 12.2 Infant aged 7 days with bilateral eyelid oedema and purulent discharge from Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

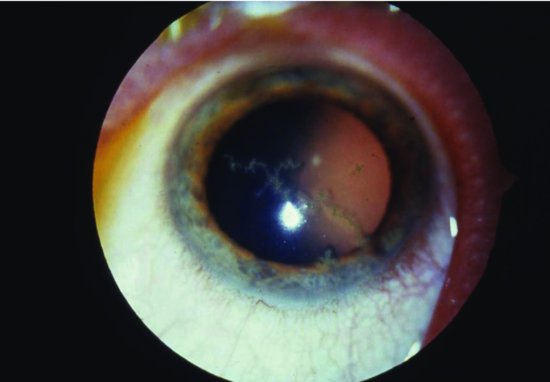

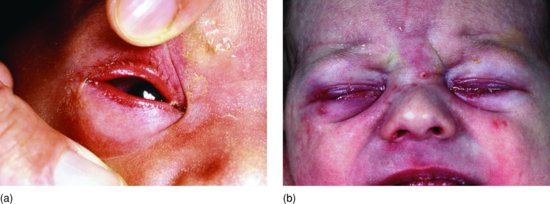

Children with HSV conjunctivitis usually acquire infection perinatally and present typically before 7 days of age, although may present from 1 to 14 days, rarely later (Figure 12.3a and 12.3b).15,16 As many as 90% of neonates with HSV conjunctivitis have discrete skin vesicles or bullous skin lesions which should alert the clinician to the diagnosis (see Chapter 17). Dendritic corneal ulceration is a characteristic but late sign of HSV infection (Figure 12.4). HSV may be localized to the skin, eye or mouth, so the baby’s skin and oral cavity should be examined carefully for lesions.15,16 HSV can disseminate rapidly, so not only should the baby be examined to exclude hepatitis, DIC and encephalitis, but treatment should be instituted urgently to prevent dissemination.

Figure 12.3 (a) Neonatal herpes simplex virus (HSV) conjunctivitis with marked conjunctivitis but no skin lesions. (b) Bilateral exudative HSV conjunctivitis with isolated herpetic skin lesions.

Pseudomonas conjunctivitis usually presents in the second or third week of life with purulent discharge and eyelid oedema and erythema. This can progress rapidly to involve the cornea and can result in perforation and panophthalmitis and be complicated acutely by septicaemia or meningitis and chronically by pannus formation.17

12.1.3 Diagnosis of neonatal conjunctivitis

The most important organisms are N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis and HSV, which need completely different methods of identification.

A Gram stain of the exudate in gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum usually reveals Gram-negative intracellular diplococci, although Neisseria meningitidis, a very rare cause of neonatal conjunctivitis, has the same appearance. Although culture is the ‘gold standard’ test, the organism is fastidious in its growth. Conjunctival swabs are preferably charcoal impregnated, calcium alginate or Dacron swabs, because other swabs inhibit growth. The specimen either needs to be inoculated onto culture media at the bedside or transported to the laboratory rapidly in suitable transport media.18 No transport medium reliably supports gonococci for more than 24 hours. Gonococci need enriched media such as chocolate agar and 5% CO2 for optimal growth. Non-culture detection of N. gonorrhoeae by nucleic acid hybridization or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification used in many laboratories has acceptable sensitivity and specificity.19,20 Gonococcal ophthalmia comes from the mother, so the mother, her partner and other sexual contacts should be screened for gonorrhoea. In addition, gonococcal ophthalmia is often associated with chlamydial infection, so the infant and the parents should be screened for Chlamydia and other sexually transmitted infections not already excluded.

Culture for Chlamydia requires special media, is time-consuming and expensive and has been superseded by non-culture techniques. In Western countries, enzyme immunoassays, PCR and direct fluorescent antibody testing of eye and nasopharyngeal secretions have all been shown to have acceptable sensitivity and specificity.20–23 In developing countries, if rapid tests are not available, Giemsa staining of conjunctival scrapings for intracytoplasmic inclusions has a sensitivity of 30–70% compared with culture or more sophisticated tests.24,25

If HSV is suspected, rapid diagnosis is important as a basis for early treatment. Conjunctival swabs and fluid from any skin vesicles should be tested using the best available rapid test. Tests with high sensitivity and specificity include PCR, ELISA and fluorescent antibody tests.15,16

Bacterial eye culture may grow an organism, but this does not guarantee causation. In a prospective case-control study from Thailand, Chlamydia and Staphylococcus aureus were isolated significantly more often from infants with conjunctivitis, whereas CoNS, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas and diphtheroids were at least as commonly isolated from controls.26 This was a small study and Pseudomonas can undoubtedly be a serious ocular pathogen. There are occasional reports of Pseudomonas endopthalmitis but also of outbreaks of invasive Pseudomonas eye infection associated with fatal septicaemia.17 A retrospective observational study from the United States of 65 NICU infants with culture-positive conjunctivitis found Gram-negative bacilli in 25 (38%), mostly Klebsiella, Escherichia coli or Serratia, and occasionally Pseudomonas or Enterobacter.27 The interpretation of a positive eye culture with a potentially pathogenic organism depends on the clinical scenario.

Other organisms that can cause neonatal conjunctivitis include Haemophilus influenzae (both untypeable and type b), Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma hominis and Candida (Section 12.2 and see Chapter 16).

12.1.4 Management of neonatal conjunctivitis

12.1.4.1 Gonococcal infection

Originally gonococcal conjunctivitis could be cured with penicillin, but penicillinase-producing strains of gonococcus are now common worldwide. Gonococcal ophthalmia is rare in Western countries and almost all recent studies have been conducted in developing countries. In an observational study in Kenya, none of 68 patients with gonococcal conjunctivitis failed treatment with a single dose of intramuscular (IM) kanamycin plus gentamicin eye ointment.28 However, kanamycin followed by saline washes did not cure all patients28 and also fails to eradicate oropharyngeal carriage in a proportion of infants.29 An RCT in Kenya compared single-dose IM ceftriaxone plus 7 days of topical gentamicin with single-dose kanamycin plus 7 days of topical gentamicin or topical tetracycline.29 There were no treatment failures in the 55 infants treated with ceftriaxone who returned for follow-up, although 6 infants did not return for follow-up. In contrast, 3 of 50 infants given kanamycin had persistent or recurrent gonococcal infection.29 In a small study, single-dose ceftriaxone cured six infants with gonococcal ophthalmia, although a seventh did not return for follow-up and two needed treatment for Chlamydia conjunctivitis.30 Ceftriaxone can displace bilirubin bound to albumin so may not be safe in jaundiced babies. Single-dose cefotaxime successfully treated ophthalmia and eradicated carriage in all 9 patients in a study in Rwanda.31 In the United States, the recommended treatment of proven gonococcal ophthalmia is with a single IM or IV dose of ceftriaxone 25–50 mg/kg to a maximum of 125 mg or with a single IM or IV dose of cefotaxime 100 mg/kg, plus immediate and regular saline irrigation.13,32 Topical antibiotics are unnecessary if a third generation cephalosporin is used. If the infant has evidence of disseminated gonococcal infection with septic arthritis, bacteraemia or meningitis, 7 days of parenteral therapy is recommended using ceftriaxone 25–50 mg up to 125 mg once daily or cefotaxime 100–150 mg/kg/day given 8 hourly. Cefotaxime is preferred for infants, particularly pre-term, with hyperbilirubinaemia.13,32–34 The evidence that single-dose therapy is effective is based on one RCT and observational studies with incomplete follow-up. The Australian Therapeutic Guidelines recommend 7 days of parenteral antibiotics for all babies with gonococcal ophthalmia and recommend adding empiric azithromycin pending investigations if there is a high risk of Chlamydia.35 Single-dose therapy should be given empirically to infants born to mothers with active gonococcal infection, even if the infant is asymptomatic.13,32–34

In most Western countries notification of public health authorities is mandatory if an infant presents with gonococcal ophthalmia to enable contact tracing and investigation for other sexually transmitted diseases. There may even be child protection issues if infection is not clearly acquired perinatally.

12.1.4.2 Chlamydial infection

The standard treatment for chlamydial conjunctivitis is oral erythromycin 40 mg/kg/day in four divided doses (10 mg/kg/dose 6 hourly). Oral therapy is preferred to topical therapy which, although it has comparable efficacy, does not eradicate carriage.36 Oral therapy is recommended to decrease the risk of subsequent Chlamydia pneumonitis, which develops in about 30% of untreated infants with nasopharyngeal Chlamydia.14 About 10–20% of infants’ conjunctivitis fails to resolve with oral erythromycin, necessitating further treatment.14,37

In a small observational study of oral azithromycin 20 mg/kg once daily, two of five babies failed to respond to 1 day. However, 3 days of azithromycin 20 mg/kg once daily successfully treated seven infants, although one remained culture positive in the nasopharynx.38

In the absence of RCTs either erythromycin or azithromycin seems appropriate.

12.1.4.3 Herpes simplex virus conjunctivitis

HSV infection is considered in Chapter 17 (see Section 17.2). The dose of aciclovir for a neonate is 20 mg/kg/dose given IV 8 hourly, 14 days for localized disease and 21 days for encephalitis.39

12.1.4.4 Bacterial conjunctivitis

Topical antibiotics speed clinical and microbiologic recovery from bacterial conjunctivitis in older children and adults, although 65% of those on placebo resolve within 2–5 days.40 There are no comparable data for neonates. If gonococcal and chlamydial infections are excluded, S. aureus is the main bacterium implicated. A review of 53 papers found that topical fusidic acid was as good as topical chloramphenicol for neonates presenting with sticky eyes.41 Topical antibiotics apart from chloramphenicol and fusidic acid sometimes used to treat bacterial conjunctivitis include tetracyclines, quinolones, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides and polymyxin, but none has been studied systematically in newborns. Sticky eyes, which may also be due to chemical conjunctivitis secondary to prophylactic agents, often resolve with saline washes without topical antibiotics.

If the neonate with conjunctivitis has periorbital redness and/or swelling (Figure 12.5) this is a worrying sign of orbital cellulitis. Maxillary osteomyelitis (see Chapter 9), which is frequently misdiagnosed as orbital cellulitis, should be considered. Even if underlying osteomyelitis is unlikely, the neonate with orbital cellulitis merits careful assessment and probably systemic antibiotics because of the risk of bacteraemia with any cellulitis.