chapter 8 Examining the Visual System

Normal Visual System in Infants and Children

In infants, the choroid gives a blue hue to the overlying thin sclera. In white persons, the iris is often poorly pigmented at birth, and the final eye color may not be established until at least 8 months of age. Examination by direct ophthalmoscopy shows the baby’s fundus to be pale, with the macula barely visible. As the child gets older, the fundus becomes darker, and the macula becomes darker than the surrounding retina. The macula then displays the easily recognized oval, bright reflection of the ophthalmoscope light, known as the macular umbo (Plate 8–1).

The birth process can be somewhat traumatic to the eyes. Many newborns sustain episcleral and retinal hemorrhages during vaginal delivery (see Fig. 4-14). These hemorrhages can be alarming to both parents and physicians but are harmless and usually disappear within 2 weeks. At birth, the nasolacrimal duct often is blocked at its junction with the nasal mucosa under the inferior turbinate. The blockage resolves spontaneously in more than 90% of cases, although it can remain until 1 year of age in some children, causing persistent tearing. A few affected children then need surgical treatment.

The process and rate of development of vision in infants are better understood than they were 10 years ago. Vision exists in several forms with different neuronal channels carrying specific visual functions, such as contrast sensitivity, orientation, movement, and hyperacuity. Each function develops at a different rate. For practical purposes, normal newborns can see a human face easily and demonstrate their visual ability by looking at it; they even follow the face with eye or head movement as it passes slowly before them at close range (Fig. 8-1). A baby’s ability to follow your face can be verified only when the baby is awake and alert, often just before or in the middle of a feeding session. This innate ability is paramount to the infant’s future development because few parents fail to form an emotional attachment to a little one who looks directly at them minutes after birth. By contrast, parents of a blind or strabismic infant who are unable to establish the interaction that comes with normal eye contact may have significantly greater difficulty developing the same level of emotional attachment to their offspring.

Definition of terms

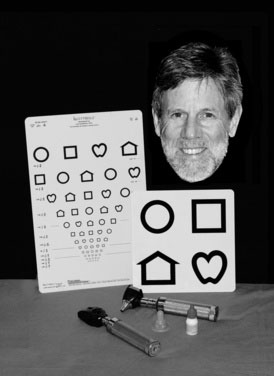

As an aid to diagnosis, this section contains a brief glossary of diagnostic terms that summarize the features to look for in children with eye problems. Box 8-1 and Figure 8-2 show the tools used to examine the eyes; Table 8-1 lists definitions and acronyms.

Table 8-1 Ophthalmologic Shorthand*

| Abbreviation/Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| Alt | Alternating strabismus; in almost all cases of strabismus, fixation (use of the eye to look at something) is with at least one eye at a time; if there is equal vision, the eyes will alternate fixation |

| APD | Afferent pupillary defect |

| CD | Corneal diameter |

| C/D ratio | Cup/disc ratio (cup size can be enlarged in persons with glaucoma) |

| CL | Contact lens |

| Comit | Comitant |

| E | Esophoria; the eye turns in only when there is interference with binocular vision (as with covering) |

| ET | Esotropia; one eye is turned in spontaneously |

| E(T) | Intermittent esotropia; the eye turns in only occasionally |

| IOL | Intra-ocular lens |

| IOP | Intra-ocular pressure |

| OD | Oculus dexter (Latin); right eye (English) |

| OS | Oculus sinister (Latin); left eye (English) |

| OU | Oculus uterque (Latin); each eye (English) |

| PERLA | Pupils equally reactive to light and accommodation |

| SLE | Slit-lamp examination |

| VA cc | Visual acuity with correction (with glasses or contact lens[es]) |

| VA sc | Visual acuity without correction |

| X | Exophoria |

| XT | Exotropia; one eye turns out (exodeviation) |

| X(T) | Intermittent exotropia; the eye turns out only occasionally |

* For example, a diagnosis of strabismus could be written as “Alt Comit X(T),” which would mean “alternating comitant intermittent exotropia.”

Cataracts

Cataracts are an important cause of leukocoria (white pupil, from the Greek; see Plate 8–2). Causes of pediatric cataracts include congenital rubella, metabolic disorders, and chromosomal anomalies. Cataracts can result from ocular inflammation (uveitis) or may accompany other ocular malformations. Many idiopathic cataracts are sporadic, but some are genetic. Some systemically administered medications cause cataracts. Steroids are common culprits, and they can cause glaucoma as well. Amblyopia in a child with a cataract is severe; therefore, cataracts in infants need immediate attention. Postoperative optical correction may require the use of contact lenses in infants, although intraocular lenses are becoming more popular in children older than 2 years.

Coloboma

A defect of closure of the embryonic fissure of the eye; hence, its inferonasal location in the eye. In mild form, only the iris is involved; in more severe cases, the choroid and the optic nerve can be involved (Plate 8–3). With optic nerve involvement, central nervous system (CNS) midline defects should be suspected, as in optic nerve hypoplasia (see definition of this term).

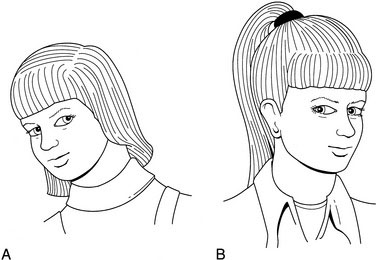

Head tilt

Abnormal head positions can be induced by a large array of conditions, many of them ocular. Typical is the compensatory head tilt seen in a fourth cranial (trochlear) nerve palsy, which is assumed to avoid diplopia and keep the eyes aligned. Without the tilt, the eyes show a vertical strabismus and the patient sees double (Fig. 8-3, A).

Head turn

An abnormal head position taken when reading or looking at a small visual target, typically caused by either a sixth cranial nerve (abducens) palsy or nystagmus. In the former, the head turn is used to avoid horizontal diplopia (Fig. 8-3, B); in the latter, the head turn improves vision by reducing nystagmic oscillations (null position).

Hemangioma (orbital, capillary)

Benign congenital tumors that grow rapidly when a child is between 1 and 6 months of age but tend to regress spontaneously later (Plate 8–4). Benign congenital tumors may cause severe amblyopia by pupillary obstruction, high astigmatism, or both. Early treatment is essential to preserve vision. Injection of steroids into the tumor, systemic treatment, glasses, and patching of the sound eye all may be necessary.

Hyphema

Bleeding into the eye’s anterior chamber (Plate 8–5). A trauma severe enough to cause a hyphema can involve other eye structures, leading to retinal detachment or injuring the trabecular meshwork of the iridocorneal angle and thereby causing glaucoma. Hyphema is the principal diagnosis in one third of eye traumas and is a major cause of ocular morbidity in children. Hyphemas rebleed in 6% of cases within 5 days of onset, causing further complications, but it may be possible to prevent rebleeding by decreasing physical activity and, in very selected cases, by administering systemic antifibrinolytic agents.

Leukocoria

A white pupil (Plate 8–2). This finding has major clinical implications. The differential diagnosis includes retinoblastoma and cataract. Delaying treatment of the former leads to death; delaying treatment of a cataract causes permanent loss of vision.

Lymphangioma

A diffuse benign tumor of the orbit that often bleeds internally and is another cause of ptosis, proptosis, or both. Almost impossible to resect completely in childhood, lymphangioma is a cause of astigmatism and amblyopia (Fig. 8-4).

Myelinated nerve fiber layer

Abnormal presence of myelin around the superficial nerve fibers of the retina near the optic disc (Plate 8–6). It can be so extensive that the pupillary red reflex can be made to appear white (leukocoria). The vision is generally normal except when the macula is heavily involved.

Optic nerve hypoplasia

A common cause of congenital blindness in children. Optic nerve hypoplasia often is misdiagnosed as optic atrophy because secondary nystagmus (sensory) makes the hypoplasia difficult to visualize. The optic nerve head (disc) is smaller than normal (Plate 8–7). Look for CNS midline defects, including the involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis with accompanying growth hormone deficiency (see Chapter 16).

Palsies (sixth, third, and fourth cranial nerves)

The extraocular muscles are innervated by various cranial nerves: the superior oblique by the fourth cranial nerve (also called the trochlear); the lateral rectus by the sixth cranial nerve; and all the others by the oculomotor nerve, the third cranial nerve, which also innervates the pupil and the ciliary body for accommodation. Any injury to these nerves induces a strabismus, the angle of which varies according to the direction of gaze—an incomitant strabismus. Typically, a head turn is seen in persons with sixth nerve palsy and lid ptosis in persons with third nerve palsy. Fourth cranial nerve palsy (trochlear) causes an ipsilateral hyperdeviation and a contralateral head tilt (see Fig. 8-3).

Periorbital cellulitis

Any inflammation around the orbit is cause for concern, and the differential diagnosis should include rhabdomyosarcoma (see later definition). When the orbital content is involved, ocular motility is decreased and the patient is at imminent risk of loss of vision. Haemophilus influenzae meningitis is an early complication in children younger than 5 years. Periorbital cellulitis (Plate 8–8) is most often associated with ethmoiditis in children who do not have a clear history of skin trauma or infection around the eye, and both computed tomography scanning and magnetic resonance imaging are invaluable for a clear evaluation of the best therapeutic regimen. This condition is far less common in areas of the world where Haemophilus influenzae B vaccine is used. Most cases of periorbital cellulitis require systemic antibiotic therapy.

Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV)

The presence of a unilateral dense residual vascularized glial frond of tissue that originates from the optic nerve disc and projects toward the back of the lens. It is the first tissue present in the eye required to initiate the growth of the lens. In PHPV, the lens is abnormal and cataractous, causing a leukocoria; the differential diagnosis of leukocoria includes other forms of cataract and retinoblastoma. PHPV is associated with microphthalmos and cataracts. The vessels in the back of the lens can bleed, inducing a very rare but diagnostic hemorrhagic cataract. PHPV is a progressive malformation that requires early surgery to save the eye and possibly restore its vision (Fig. 8-5).

Plexiform neurofibroma

A type of hamartomatous formation found in persons with neurofibromatosis. In the orbit, it is accompanied by sphenoid bone defects with herniation of the contents of the anterior fossa into the orbital cavity. This condition may or may not cause visual problems, such as strabismus, astigmatism, and optic nerve dysfunction (Fig. 8-6).

Retinitis pigmentosa

A generic term describing a variety of retinal degenerations, including choroidal degenerations, diseases of either type of photoreceptors, and syndromes involving other organ systems (e.g., Laurence-Moon-Biedl and Alström syndromes in which progressive retinal degeneration is associated with obesity and other systemic dysfunctions) (Plate 8–9). Most patients with retinitis pigmentosa experience a severe visual deficit at an early age.

Retinoblastoma

The most important cause of unilateral or bilateral leukocoria, retinoblastoma occurs in 1 in 15,000 births and often is also present with a strabismus or a red eye (Plate 8–10). The gene for this condition is located on the long arm of chromosome 13. Retinoblastoma is most curable if diagnosed early. Later death from a second malignancy is a major concern in bilateral and autosomal dominant familial cases.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree