PRACTICE POINT Chaperones

PRACTICE POINT Chaperones PRACTICE POINT Age-specific approach to examining children

PRACTICE POINT Age-specific approach to examining children- Newborn infants: in the early weeks of life, patience, warm hands and a quiet voice are needed. Bedside manner contributes little (but is important to parents).

- 2–10 months: infants respond to the friendly doctor, and examination is often easy if the child is generally comfortable. A smiling face can evoke rapport, and even cooperation.

- 10 months–5 years: toddlers present the biggest challenge. The toddler is generally suspicious of strangers. Their confidence must be won, perhaps by giving them something to hold, or taking interest in their toy. An unhurried, confident approach is most likely to lead to success. Young children do not like to be separated from their parents, rapidly undressed or made to lie flat. Examine the child on their parent’s knee rather than an examination couch. Be patient and adapt the pace and the order of the examination to the child’s level of comfort and confidence.

- 5–10 years: school-age children are used to being without their parents, but still want them close by in unfamiliar surroundings. They are generally cooperative. They enjoy neurological examination and like to listen to their heart through a stethoscope. A worried child can be diverted by chatting to them.

- 10 years to teenage: the process of examining the older child and teenager is usually straightforward. Cooperation is almost guaranteed if the doctor respects their independence, maturity and modesty. Ask them whether they would prefer their parents to be present, and seek their permission to examine them. Often the history-taking will be dominated by a parent, and most teenagers cannot tell you their birthweight! The time of the examination is an opportunity to talk to the older child about their perspective and concerns.

3.1 A system of examination

In acute paediatrics, outpatients and in undergraduate exams, clinical examination begins with general assessment and then moves on to look at specific systems. All who are new to paediatrics must begin by learning these skills.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTA good history will raise specific questions, e.g. this history could be pneumonia. Is this child unwell? Is she tachypnoeic or febrile?

3.1.1 Initial assessment

Clinical examination has certain essential elements; these are made during the first approach to the child and should be carefully recorded. The most striking finding in a young child with pneumonia, for example, is that they appear ill. The positive clinical findings of lobar consolidation are difficult to elicit, and may be absent.

3.1.2 Highcost

This acronym emphasizes the importance of the first clinical impression and simple observation, which are central to good paediatric clinical assessment. It might also remind you that good clinical assessment is expensive of time, but highly cost effective! It is a useful approach to systems examination in the OSCE (Chapter 28).

3.1.3 Hello

Children are quick to assess adults, and often very accurate. Approach the child with courtesy, a smile and a friendly greeting. There are two essential reasons that every undergraduate should remember this: it is an important clinical skill, and in almost every OSCE you will get marks for it!

3.1.4 Introduce yourself

Introduce yourself and find out to whom you are speaking. What does the child like to be called? Matt may only be called Matthew when his parents are annoyed with him.

3.1.5 General inspection

During the general introduction, and often while taking the clinical history, you will learn a lot about the child, her parents and the relationships between them. You should also note if the child has an unusual appearance or abnormal features which fit into a recognized pattern (e.g. Down syndrome, achondroplasia).

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTNote the following:

- Does the child look well cared for? (Be careful – some clean, well-behaved children are unloved, while some caring parents may not see hygiene and clothing as a priority.)

- Is there a loving relationship between the child and the parents? Do the parents talk as if the child were not there, or as if she is an inanimate object? Are the parents showing an appropriate level of concern whilst sharing the problem with you?

- Is the child confident or clinging to the parent? Is he crying? When he seeks reassurance from his parent, does he get it? These are difficult assessments, particularly when a child is unwell.

- Does the child have any unusual features? Are the body proportions appropriate? Look at the child’s face. Before you decide a child is dysmorphic, look at the parents’ faces.

3.1.6 Health and hands

- Is the child ill or well? Ask yourself this question every time you examine a child.

- In the young child, this is often the most important clinical sign. In the acutely unwell, 6-month-old infant, a pale, listless unresponsive appearance with glazed eyes has essential implications for diagnosis and immediate management. The experienced parent who simply reports that their child is ill should be listened to carefully.

Children can change very quickly. A child who was satisfactory at triage may be moribund an hour later. If in doubt, don’t press on with your assessment but call a member of staff.

Children can change very quickly. A child who was satisfactory at triage may be moribund an hour later. If in doubt, don’t press on with your assessment but call a member of staff.Facial appearance may be helpful. Look for swelling, pallor, jaundice, or cyanosis and assess hydration (see Figure 21.4). Jaundice may be difficult to detect in artificial light. Examine the palprebral conjunctiva for signs of anaemia (evert the lower eyelid).

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT- Features that raise concern:

- A child who is inattentive, limp or intermittently distressed

- pallor, mottled skin or the infant who appears grey

- hypoxia may make a child sleepy or agitated

- cyanosis may be hard to see

- dehydration (Section 21.1.4.1)

- increased work of breathing (Section 3.5.3)

- fever, particularly if there is no clear cause.

- A child who is inattentive, limp or intermittently distressed

It is often helpful to start the examination by holding the child’s hand. It is not only a friendly gesture, but is often informative.

- Quickly assess the pulse. The radial pulse is commonly used, but in infants the brachial may be easier to feel.

- Assess perfusion. Are the hands well perfused or cold and clammy?

- Capillary refill is assessed by gently squeezing the nail so that the nail bed becomes pale. Upon release, the nail bed should again become pink within 2 seconds. Pale hands may indicate anaemia, which is better assessed from the conjunctiva.

- Look for clubbing. Although uncommon in children, when present it is an important physical sign.

3.1.7 Centiles

Assessment of growth is a fundamental part of paediatric examination (see below). Although with experience you can make some assessment visually, you should always plot measurements on a centile chart. In an exam, saying that you would like to do this may be all that is necessary. If possible, compare with previous measurements in the parent-held record or the hospital notes. The trend of the plots is more important than their absolute positions.

3.1.8 Obvious

It is surprisingly easy to omit or even not notice the obvious, especially when you are focusing on a particular system, so include this as a deliberate step in your assessment. Often these observations give important clues to the diagnosis. Record or comment on the leg in plaster, the central venous line, the nasogastric tube, ankle/foot orthoses (splints) or a pile of inhalers. Record any injuries.

3.1.9 Systems examination

In paediatrics, each system does not need to be examined in a fixed order. Often examination of the body systems must be opportunistic. If the toddler is undressed and lying peacefully in his mother’s arms, you might begin by listening to the heart. Leave potentially upsetting procedures (inspection of the throat) until last. Many children prefer not to be undressed completely, although by the end of examination all parts of the body should have been inspected. In undergraduate examination, genitalia should not be examined, except in young infants, and rectal examination should never be performed. During systems examination, put the child at ease by asking about their family, friends, pets, hobbies or favourite TV programmes. Keep any instruments (tendon hammer, auroscope, etc.) out of sight until you need them, then show them to the child and explain how they work.

3.1.10 Thank you

Gratitude for the privilege of examining a child is never misplaced. The family will all appreciate praise for a child’s good behaviour and cooperation.

OSCE TIP

OSCE TIP3.2 Growth and nutrition

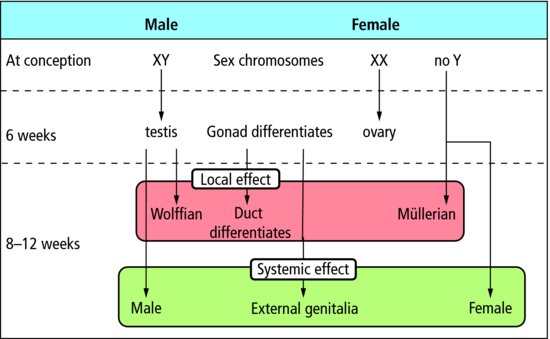

The characteristics of children which most clearly distinguish them from adults are growth (increase in size) and development (organ maturation, sexual development and the acquisition of new skills) (Figure 3.1).

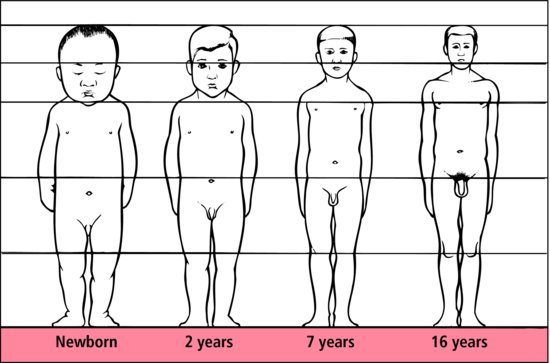

Figure 3.1 Body proportions from birth to adulthood. The ratio of the parts above and below the symphysis pubis falls from 1.7: 1 in the newborn to 0.9: 1 in the adult.

PRACTICE POINT

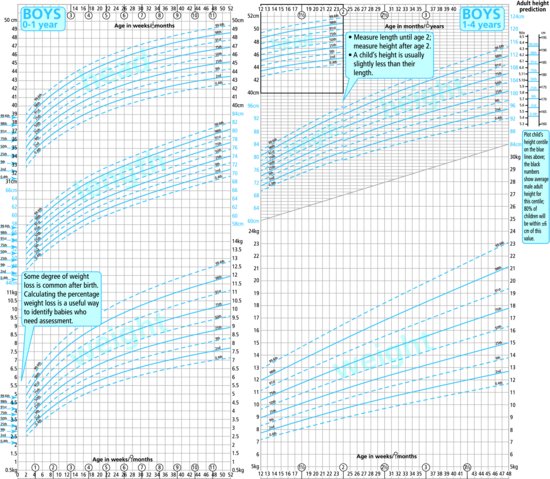

PRACTICE POINT3.2.1 Centile charts (Figure 3.2)

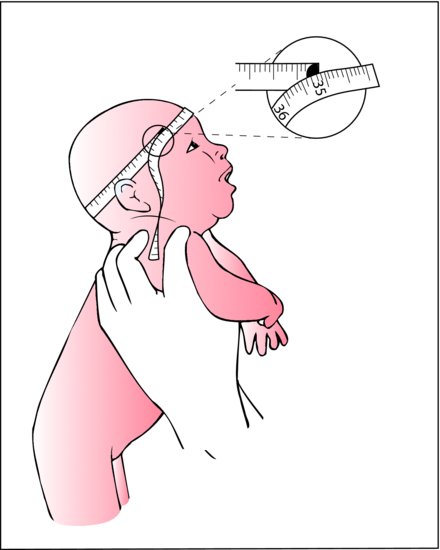

To assess growth, plot weight and height (and head circumference in infants, Figure 3.3) on centile charts. These are constructed from measurements of many children who are free from recognized problems which affect their growth. Children should be weighed either in underclothes (babies in nappies) or naked, but always the same way because changes in weight are more important than absolute values. Height is measured with a wall-mounted stadiometer, and you need tuition and practice to be able to do this accurately. For a child who is not yet walking, measure length supine on a horizontal stadiometer with a moveable foot board. Two people are needed to do this accurately. If children are upset at the prospect of being weighed and measured, postpone until the clinical examination is over: tears are more easily prevented than stopped.

Figure 3.2 Growth centile charts for boys aged 0-4 years. Separate charts are available for girls and older children at www.rcpch.ac.uk/child-health. These charts are developed and maintained by RCPCH/WHO/Department of Health. © 2009 Department of Health.

Figure 3.3 Measuring an infant’s head circumference: • head circumference is an important measurement, and reflects the volume of the cranial contents with surprising accuracy;

- a good quality, inelastic tape is used;

- the tape passes over the occiput, above the ears, and the prominence of the brow;

- two or three measurements are taken in slightly different planes, and the largest is recorded as the head circumference.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT3.2.2 Normal growth

Growth rates are good indicators of general health and nutrition. Children who are growing normally usually have height and weight measurements that progress parallel to the centile lines, are in proportion (i.e. not more than 2 centile lines difference between height and weight). 95% of healthy children are between the 2nd and 98th centiles.

3.2.3 Growth velocity and puberty

Growth velocity refers to gain in weight or height over time. Height velocity is measured in cm/year. It is highest in the first year and then gradually falls until the pubertal growth spurt when there is a second smaller peak. Depending on whether puberty starts early or late, a child’s height and weight may move away from their ‘normal’ centile around this time. If puberty is early, growth will accelerate towards a higher centile, and then gradually level off as the rate of the pubertal growth spurt slows. Full assessment of height may require information about pubertal status (Figures 3.5 and 3.6) and bone age (see Section 3.2.5).

Figure 3.5 Stages of male genital development. (1) Pre-adolescent. (2) Enlargement of scrotum and testes. (3) Increases of breadth of penis and development of glans. (4) Testes continue to enlarge. Scrotum darkens. (5) Adult: by this time, pubic hair has spread to the medial surface of the thighs.

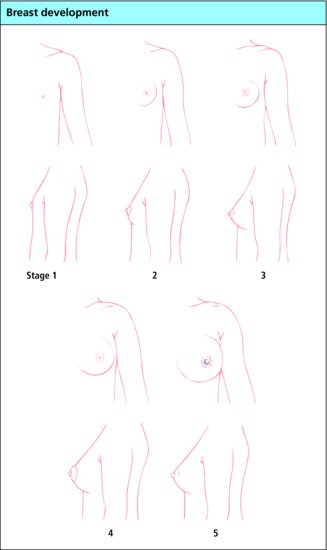

Figure 3.6 Stages of breast development. (1) Pre-adolescent – elevation of papilla only. (2) Breast bud stage. (3) Further enlargement of breast and areola. (4) Projection of areola and papilla above level of breast. (5) Mature stage – areola has recessed, papilla projects.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree