CHAPTER 68 Evidence-based care in gynaecology

Introduction

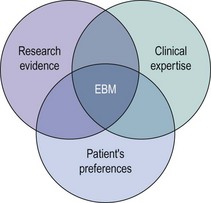

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been defined as the ‘conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett et al 1996). It incorporates three fundamental elements: external research evidence, clinical expertise, and patients’ views and values in the delivery of health care (Figure 68.1).

Evidence-Based Medicine Processes

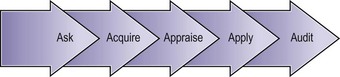

A fifth ‘A’ for ‘Audit’ can be added to these steps to take EBM beyond the care of the individual patient (Figure 68.2).

Formulation of a structured question

A well-structured question is essential in order to get the right clinical answer. It also facilitates the process of searching for evidence. A suggested approach uses five components (PICOD: Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome(s) and Design), as shown in Table 68.1.

Table 68.1 Components of structured clinical questions

| Component | Example 1 | Example 2 |

|---|---|---|

| P: Population, patient or problem | In women suffering with heavy menstrual bleeding… | In postoperative women with swollen legs… |

| I: Intervention (test, medical or surgical treatment, or process of care) | … would treatment with norethisterone… | … would a Doppler ultrasound be accurate… |

| C: Comparison (placebo, another alternative treatment or the gold standard in a diagnostic accuracy study) | … compared with no treatment at all or alternative treatments (e.g. levonorgestrel IUS)… | … compared with venography as the gold standard… |

| O: Outcome(s) | … lead to an improvement in their symptoms? | … in diagnosing deep venous thrombosis? |

| D: Ideal design for the study | A randomized controlled trial | A test accuracy study |

IUS, intrauterine system. Produced by Bob Phillips, Chris Ball, Dave Sackett, Doug Badenoch, Sharon Straus, Brian Haynes, Martin Dawes since November 1998. Updated by Jeremy Howick March 2009.

Searching the literature

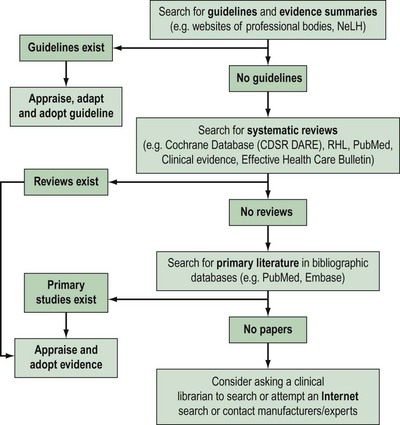

Approximately 17,000 journals collectively publish over 1 million biomedical articles each year. Identifying relevant articles will require the use of apposite keywords (and their combinations) to search appropriate databases. A hierarchical approach to literature searching is recommended (Figure 68.3).

The first step is to look for an up-to-date professional guideline that has been developed on the basis of systematic appraisal of available evidence. Table 68.2 lists some sources of guidelines and evidence summaries. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) has long acknowledged the need to update clinical practice on the basis of research findings. Since 1973, the RCOG has regularly convened study groups to address important growth areas within the specialty. These groups have met, evaluated the results of research and conducted in-depth discussions on a variety of topics. These discussions have shaped the development of clinical recommendations which were initially based on consensus. Over the years, this approach has been modified in order to produce genuine evidence-based guidelines. To be effective and relevant, guidelines must fulfil fthe following three essential criteria.

Table 68.2 Sources of guidelines and evidence summaries (relevant for gynaecology)

| Sources of guidelines and evidence summaries | Website |

|---|---|

| Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) | www.rcog.org.uk |

| American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) | www.acog.org |

| The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) | www.sogc.org |

| The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) | www.ranzcog.edu.au |

| International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) | www.figo.org |

| Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FFPRHC) | www.ffprhc.org.uk |

| British Fertility Society (BFS) | www.britishfertilitysociety.org.uk |

| British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) | www.bgcs.org.uk |

| British Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (BSCCP) | www.bsccp.org.uk |

| British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) | www.rcog.org.uk/bsug |

| British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (BSGE) | www.bsge.org.uk |

| The Association of Early Pregnancy Units (AEPU) | www.earlypregnancy.org.uk |

| The NHS National Library for Health (NLH) | www.library.nhs.uk |

| The National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence (NICE) | www.nice.org.uk |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) | www.sign.ac.uk |

| NHS Clinical Knowledge Summaries (NHS CKS; formerly PRODIGY) | www.cks.library.nhs.uk |

| The National Guideline Clearing House (NGC, US) | www.guidelines.gov |

In the absence of credible evidence-based guidelines, the next step would be to search for an up-to-date, good-quality, systematic review. Some sources of systematic reviews are given in Table 68.3.

Table 68.3 Sources of evidence

| Systematic reviews | |

|---|---|

| Sources of systematic reviews | Website |

| The Cochrane Library | www.cochrane.org/reviews/ |

| The CRD databases (including DARE) | www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb |

| The Pubmed Systematic Reviews Search Filter | www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/clinical.shtml |

| Bandolier | www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier |

| The WHO Reproductive Health Library (RHL) | www.rhlibrary.com |

| Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database | www.ncchta.org/project/htapubs.asp |

| Sources of primary literature | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sources of primary literature | Subject matter | Website |

| Pubmed (Medline) | Medicine, bioscience | www.pubmed.gov |

| EMBASE | Medicine, pharmacology, nursing | www.embase.com |

| CINAHL | Nursing and allied health care | www.cinahl.com |

| AMED | Allied and alternative health care | www.bl.uk (search for ‘AMED’) |

| BNI (British Nursing Index) | Nursing | |

| HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium) database | Health management | |

WHO, World Health Organization; CRD, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; DARE, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness.

Apart from the traditional sources of systematic reviews, such as the Cochrane Library and DARE, MEDLINE and Pubmed have now become a rich source of systematic reviews. Pubmed contains a systematic review filter within Pubmed Clinical Queries (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query/static/clinical.shtml), and MEDLINE has the indexing term ‘reviews, systematic’ as a ‘publication type’.

If no systematic reviews are identified, or if reviews are out-of-date, non-systematic or of marginal relevance to the clinical question, it is necessary to continue the literature search for primary studies. Table 68.3 provides a list of important sources of primary literature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree