chapter 9 Evaluating the Respiratory System

Obtaining the History

Parents must understand your terminology, and you must understand theirs (see Chapter 1). What parents describe as a wheeze may, in fact, be stridor. What you call asthma may mean something much more alarming to parents. Do not assume that parents understand what is meant by terms such as wheeze. Be prepared to imitate a wheeze, stridor, or whoop, or ask the parents to imitate the sound they are trying to describe.

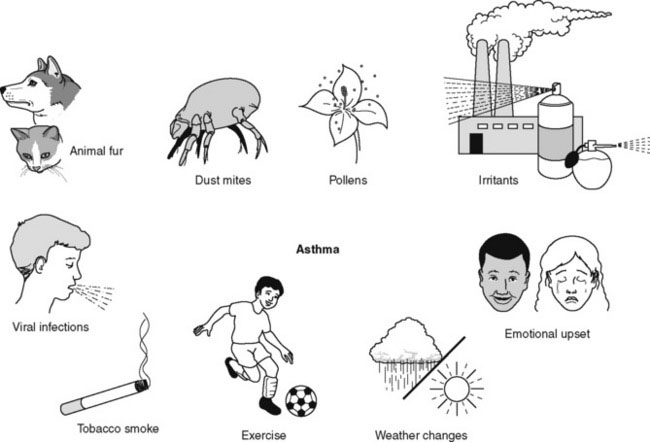

Some parents have difficulty recalling the circumstances or triggers that cause or aggravate their child’s respiratory symptoms. This situation occurs frequently in children with asthma. Have a prepared list of common asthma triggers on hand to help them (Fig. 9–1).

Chief complaints

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree