chapter 4 Evaluating the Newborn

Diagnostic Approach

Obtaining the History

Table 4–1 lists the important issues to ask about when obtaining any antenatal history.

TABLE 4–1 Significant issues to ask about when taking the History for a Newborn

| Mother’s past pregnancies and their outcome | No. of pregnancies |

| Stillbirths | |

| Abortions | |

| Neonatal deaths | |

| Cesarean sections | |

| Specific concerns that parents may have about current pregnancy because of past experiences | |

| Preexisting systemic illness in mother and maternal medications | Hypertension |

| Depression | |

| Diabetes | |

| Seizure disorder | |

| Thyroid disease | |

| Cardiac disease | |

| Metabolic disorder (phenylketonuria) | |

| Genetic history | History of inherited disorders |

| Consanguinity | |

| Unexplained neonatal deaths in the family | |

| History of current pregnancy | Date of last menstrual period |

| Use of assisted reproductive technologies or fertility treatments | |

| Estimated date of conception by dates (and by ultrasonography if early ultrasonogram [9–13 weeks] available) | |

| Results of ultrasonography, amniocentesis, cordocentesis, chorionic villus sampling | |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes | |

| Note maternal weight gain and blood pressure, fetal growth, blood type | |

| History of alcohol use, drug use (prescribed or illicit), cigarette use | |

| Group B Streptococcus status (if known) | |

| History of maternal surgery during pregnancy | |

| Concerns about placenta (e.g., placenta previa or thickening) | |

| Use of magnesium sulfate, betamethasone | |

| Current labor and delivery | Induced or spontaneous labor (if induced, why?) |

| Time of rupture of membranes and quality of amniotic fluid (bloody, meconium-stained) | |

| Length of second stage | |

| Use of medications (analgesics and time prior to delivery) | |

| Intrapartum fever and antibiotics | |

| History of fetal distress | |

| Presentation (vertex, breech, transverse) | |

| Vaginal or cesarean delivery (if cesarean, why?) | |

| Use of forceps or vacuum extraction | |

| Adaptation to extrauterine life | Apgar scores |

| Resuscitation needed? If so, what and for how long? | |

| Need for naloxone |

Approach to Physical Examinations of the Newborn: When, Why, and How

The first examination

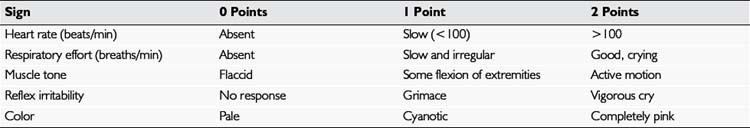

The method used almost universally in delivery rooms to evaluate the central nervous system (CNS) status and general adaptation of the neonate to extrauterine life is the Apgar score. This scoring system, summarized in Table 4–2, evaluates the baby in five different respects: heart rate, respiration, color, muscle tone, and reflex irritability (response to stimulation). These signs are usually evaluated at 1 minute and 5 minutes after birth. The Apgar score is the total of the baby’s scores for each of the five signs. To be consistent, have the Apgar score recorded by an experienced clinical observer whose principal responsibility is caring for and evaluating the baby. Because inter-observer variation in scoring may be considerable, experience is essential. Evaluate the signs at exactly 1 minute and 5 minutes to establish the score, especially in relation to muscle tone and reflex irritability. The latter is usually elicited by firmly stroking the sole of the foot; the appropriate response to this stimulation is a vigorous cry.

Clinical Observations and What They Mean

Encourage the parents to participate as much as possible in the examination by undressing the baby, holding the baby on the lap or the bed, and providing a stabilizing finger for the baby to grasp (Fig. 4–1). The first part of the examination is the most important. Do not touch the baby except to remove all clothing gently. You may wish to leave the diaper on until you are ready to examine the lower portion of the baby. The baby should be undressed, warm, and well illuminated and should be helped to feel stable and secure on the examining surface. Improving the baby’s stability and relaxation by letting him or her grasp the parent’s or your finger allows an immediate appreciation of the strength of the baby’s reflex grasp and reduces the tendency for instinctive startle reflexes that occur when the baby feels unstable and rolls on the examining surface.

FIGURE 4–2 Cutis marmorata (“marble skin”) can occur as a normal phenomenon when the baby is exposed.

Primitive Reflexes

Moro reflex

Newborns often demonstrate the Moro, startle, or embrace reflex spontaneously when they are suddenly moved, exposed to a sudden loud noise, given the feeling of falling, or feel unstable on a flat surface. You can most reliably elicit this reflex by allowing the infant’s head to drop (while supporting it gently) below the level of the rest of the body while the baby is in a reclining position. The baby extends the arms suddenly and rapidly with the hands open, then brings them back together more slowly in a movement that looks like an embrace. The initial rapid movement may be accompanied by a grimace or cry (Fig. 4–3). Symmetry of movement is important. Weakness of one arm (e.g., in an infant with brachial plexus injury) results in an asymmetric Moro reflex.

Palmar grasp

Find the palmar grasp by placing your index fingers in each of the baby’s open hands; the baby’s fingers should close around your fingers with strength enough to lift the baby’s body part of the way off the bed or table (Fig. 4–4).

Plantar grasp

A strong plantar grasp usually can be demonstrated if you place your thumb on the sole of the baby’s foot in the space under the toes (Fig. 4–5).

Placing and propulsive (stepping and walking) reflexes

If there is any doubt about the integrity of the baby’s CNS, either because of the history (difficult labor, delivery, traumatic procedures, or birth asphyxia) or because of associated physical findings, such as an abnormal cry, major deformities, or malformations, a more complete neurologic examination should be conducted (see Chapter 13).

Weighing and Measuring

For the physician’s and the parents’ records, it is important to (1) measure the baby’s head circumference, length, and weight accurately and (2) assess the nutritional status. Measure the head circumference, preferably with a disposable tape measure, around the largest occipital-frontal diameter across the forehead, just above the eyes, and over the most prominent part of the occiput (Fig. 4–6). Head circumference normally measures 33 to 37 cm in a full-term infant. If a baby’s head circumference measures slightly above or below the normal for age, check the parents’ head circumferences before “pushing the panic button.” Benign familial megalencephaly, a normal variant, is the most common cause of a larger than average head. The condition can be verified by checking the head circumference of both parents. Megalencephaly is usually handed down by the father.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree