ESOPHAGEAL DISORDERS

H2 blockers (e.g., ranitidine)

• Block two-thirds of acid

• Histamine stimulation is one of the three stimulants to parietal cells

• Histamine potentiates gastrin and acetylcholine

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Refractory GERD

b. Peptic ulcer disease (PUD)

c. Mallory-Weiss tear

d. Duodenal ulcer disease

e. Pleurisy

Answer a. Refractory GERD

The patient’s symptoms are classic for GERD: sore throat, metallic taste or at times a bitter taste, hoarseness, chronic cough, and wheezing. This patient also has been on optimal PPI therapy without improvement and therefore can be labeled as refractory GERD.

PUD gives abdominal pain that may or may not be worsened with eating. Duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer are two types of PUD. The pain of duodenal ulcer is more often improved with eating. This difference with the pattern of pain in relation to food is not sufficient by itself to distinguish between a duodenal ulcer and a gastric ulcer. A Mallory-Weiss tear gives hematemesis preceded by retching and vomiting. Pleurisy or pleuritis is chest pain with deep breathing.

The patient is advised to continue his PPI medications for 3 more months but is counseled on making therapeutic lifestyle changes.

Everyone on a PPI has a high gastrin level. Low acid = High gastrin

Which of the following is most likely to improve this patient’s symptoms?

a. Weight loss

b. Avoiding tight-fitting garments

c. Avoid spicy foods

d. Chewing gum

e. Eating peppermint

Answer a. Weight loss

Of all lifestyle modifications, weight loss and elevating the head of the bed reduce symptoms the most. Dietary medications help, but such modifications increase noncompliance to changes because of restriction of enjoyable foods. Tight-fitting garments and gum chewing have not been shown to change outcomes, and peppermint actually makes GERD worse.

• Dysphagia

• Weight loss

• Anemia

• Blood in stool

Long-term side effects of PPI therapy:

• Osteoporosis

• Increased risk of Clostridium difficile infection

• Community-acquired pneumonia

Gastric acid is needed to properly absorb calcium (Ca++).

PPIs Irreversibly block the hydrogen/potassium adenosine triphosphatase enzyme system (the H+/K+ ATPase).

What is the best next step in management of this patient?

a. Upper endoscopy

b. Esophageal manometry

c. Continue PPI therapy for another 6 months

d. Change to another PPI

e. Start baclofen

Answer b. Esophageal manometry

This patient clearly has refractory GERD despite optimal medical therapy and, in addition, no longer wishes to take medications. The patient needs a surgical or endoscopic procedure to tighten his lower esophageal sphincter. The best next step in management is now to refer for esophageal manometry as part of the preoperative workup before antireflux surgery. Upper endoscopy has already been performed in this patient; continuing PPI therapy for longer will not work because he is already on twice-daily regimen. There is currently no difference between PPIs, so changing from one to another will not change outcomes. Last, although baclofen and prokinetic agents have been shown to reduce GERD episodes, because of their numerous side effects, neither class of medications is used adjunctively to treat GERD.

Barrett’s esophagus: Columnar metaplasia (Figure 7-1)

Figure 7-1. Endoscopic appearance of Barrett’s esophagus. (Reproduced, with permission, from Jajoo K, Saltzman JR. Barrett esophagus. In: Greenberger NJ, Blumberg RS, Burakoff R, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Gastroenterology, Hepatology, & Endoscopy. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.)

Barrett’s esophagus leads to adenocarcinoma, not squamous cell cancer.

Antireflux surgery is the correct answer when the case describes:

1. Failed optimal medical treatment

2. Noncompliance or refusal to take lifelong medications

3. Severe esophagitis

4. Stricture formation

5. Barrett’s columnar-lined epithelium (without severe dysplasia or carcinoma)

Which of the following is the mechanism of GERD?

a. Incomplete relaxation of lower esophageal sphincter (LES)

b. Helicobacter pylori effect

c. Excess acid production

d. Increased myogenic reactivity

e. Columnar metaplasia of esophagus

Answer a. Incomplete relaxation of lower esophageal sphincter (LES)

GERD is not from Helicobacter spp.; it is from an inappropriate level or relaxation of the LES. Excess acid production is the mechanism of gastrinoma or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Columnar metaplasia is Barrett’s esophagus.

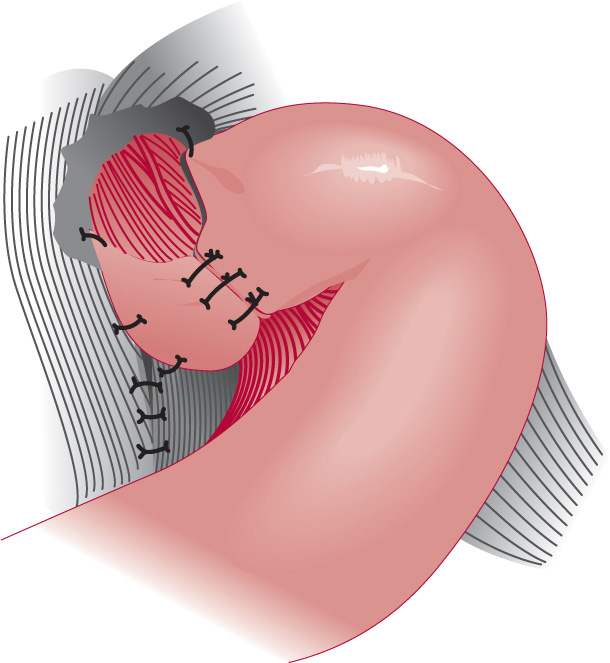

Nissen fundoplication

• Reduces symptoms in 85% to 90% of patients.

• Tightens the sphincter by wrapping the stomach around the lower esophagus

Nissen fundoplication (Figure 7-2)

• 360-degree “wrap” or collar around the esophagus Dor fundoplication

• 180-degree wrap around the esophagus

Figure 7-2. Nissen fundoplication (360 degrees) (Reproduced, with permission, from Doherty GM, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Surgery. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010.)

Which of the following is a complication of Nissen fundoplication?

a. Gas bloat syndrome

b. Diarrhea

c. Constipation

d. Malabsorption

e. Vomiting

Answer a. Gas bloat syndrome

Gas bloat syndrome is the inability to eliminate swallowed air or gas from carbonated beverages or foods by belching. Treatment is with simethicone. A patient cannot get diarrhea or constipation from an esophageal treatment. Also, a patient cannot vomit when his or her sphincter has been tightened.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

a. Peptic ulcer disease

b. Traumatic viscous injury

c. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

d. Boerhaave’s syndrome

Answer d. Boerhaave’s syndrome

The most common cause of esophageal perforation is iatrogenic or secondary to endoscopy. The term Boerhaave’s syndrome is reserved for perforations that are spontaneous and caused by vomiting. Other causes include pill esophagitis, caustic ingestions, and infectious ulcers in patients with AIDs.

This patient presents with severe chest pain that occurred after repetitive bouts of vomiting for an extended period of time. That, combined with the findings of subcutaneous air (known as Hamman’s sign) and decreased breath sounds in the left lower lung base caused by pleural effusion, leads to this diagnosis. These patients can also have concomitant pneumothorax, but in this patient, breath sounds are bilateral, and the trachea is midline. Traumatic viscous injury is rare in the setting of a case without trauma, and GERD is a mucosal disease. Perforated peptic ulcers would present with abdominal pain with no subcutaneous air in the chest.

What is the best next step in management of this patient?

a. Consult surgery

b. Intravenous (IV) fluids and antibiotics

c. Upper endoscopy

d. Barium esophagram

e. Discharge the patient home

Answer b. Intravenous (IV) fluids and antibiotics

Whenever a patient appears unstable or toxic, the next step in management is always IV fluids to raise the blood pressure. These patients should be transferred to the intensive care unit. Antibiotics that cover gut flora (such as imipenim–cilastin, piperacillin–tazobactam, or ampicillin–sulbactam) should be used. If a cephalosporin (such as cefepime) or a quinolone (such as ciprofloxacin) is chosen, metronidazole must be added. Cefepime, as with most cephalosporin antibiotics, does not cover anaerobes. Consulting surgery is important but does not take precedence over resuscitation because this patient is febrile and tachycardic. Two systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria are observed, and with a perforation, sepsis is imminent. If respiratory distress is encountered, intubation should be ordered. Upper endoscopy is controversial with suspected perforation and may worsen the condition to air insufflation. Barium esophagram is the distractor choice and the most common wrong answer. Remember that barium is caustic and not water soluble and will lead to chemical pneumonitis as it extravasates through the perforation. If a contrasted procedure is absolutely essential, we would use Gastrografin, which is water soluble. Barium, if it went through the perforation and into the pleural space, would be a disaster.

Discharging the patient is the best way to ensure death because an untreated esophageal perforation carries a nearly 100% mortality rate. The most common source for infection in esophageal perforation is mediastinitis, which classically sets in hours after viscous injury.

Boerhaave’s syndrome = Full thickness

Mallory-Weiss tear = Limited to submucosa only

The five layers of the esophagus from outside in are:

1. Adventitia

2. Muscularis propria

3. Submucosa

4. Lamina propria

5. Mucosa

What is the best initial test for esophageal perforation?

a. Upright chest radiography

b. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan

c. Chest magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

d. Upper endoscopy

Answer a. Upright chest radiography

The best initial test for esophageal perforation is an upright chest radiography, which will show free meditational air and a left-sided pleural effusion in approximately 65% of cases. Although chest CT and sometimes MRI or endoscopy can be used, Step 3 is very big on your knowing the order in which to use tests. They will not want you skipping an easy test such as a chest radiograph to jump straight to a chest CT. The most common location for esophageal perforation is at the left posterolateral wall of the lower third of the esophagus 2 to 3 cm before the stomach.

Esophageal perforation can also be confirmed by water-soluble contrast esophagram (Gastrografin), which reveals the location and degree of tear. CT scan can also be used and will show esophageal wall edema and thickening, extraesophageal air, periesophageal fluid, mediastinal widening, and fluid in the pleural sac.

Boerhaave’s syndrome is Caused by a sudden increase in intraesophageal pressure combined with negative intrathoracic pressure caused by straining or vomiting.

What is the best next step in management of this patient?

a. Surgical repair

b. Observation for several days

c. Wait for the results of blood cultures

d. Repeat endoscopy to assess for spontaneous closure in 2 to 3 days

Answer a. Surgical repair

The next step in the management of this patient is surgical repair. Surgery is the mainstay of therapy in patients with perforation. Primary surgical repair with concomitant debridement, irrigation, and resection or diversion if diseased necrotic esophagus is needed. A feeding jejunostomy is also be placed to avoid using the esophagus for 1 to 2 weeks. The most common reason for death in esophageal perforation is a delay in a diagnosis. The mortality rate approaches 50% if the diagnosis is delayed beyond 24 hours. The most common postoperative infections include abscess, mediastinitis, and tracheoesophageal fistulas.