2 Epidemiology and the Care of Children with Complex Conditions

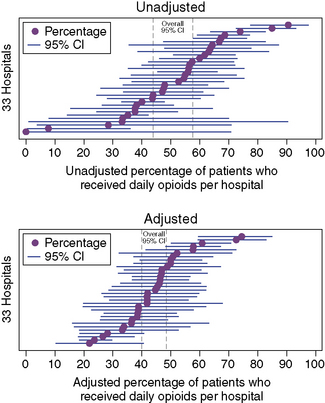

In this chapter, we apply an epidemiologic framework of investigation to the issues and challenges that we confront in pediatric palliative and hospice medicine. When people casually refer to the epidemiology of a particular illness or disease, they often mean the body of knowledge about the condition—who it affects and why, what happens to persons with the condition, and what is known about the effect of treatment for the condition—that has been built up through epidemiologic research. We try to encapsulate some of what is known about pediatric patients who receive palliative and hospice care, or more broadly children who die, while acknowledging that because these children suffer from a variety of conditions, ranging from acute trauma to complex and chronic, we must be. While presenting this information, we will also emphasize a systems-oriented perspective to the study of pediatric palliative and hospice care. While the Hippocratic practitioner of the medical art who authored the opening epigraph certainly emphasized core aspects of this systems perspective, we need to expand our practice and our science beyond the disease, patient, and a single healer. Many readers likely already consider the experience of individual children as best understood in the context of their family and healthcare, education, and other social services, as well as the systems of payment for services and laws and regulations that influence these other systems (Fig. 2-1). Our scheme is no more complicated than this common sense of the hierarchy of influences on the lives of children with life-threatening illness. Such a scheme provides not only an organized approach to the study of pediatric palliative and hospice care, but also provides insights as to how we can improve these systems. To make this scheme as down-to-earth as possible, we will over the course of the chapter illustrate aspects of the different levels by tracing the profile of a single child.

Fig. 2-1 Multi-level systems influencing experience of children receiving palliative or hospice care.

Patients and Individual-Level Systems

Conditions and diseases

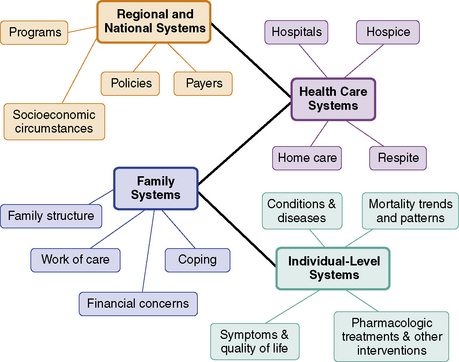

Not all children who die receive palliative care services, but national profiles of children who die provide the strongest epidemiological evidence to characterize the conditions and diseases of children receiving pediatric palliative care. Examining mortality data in the United States between 1999 and 2006 (Fig. 2-2), one notices immediately that infant deaths are due mostly to specific perinatal conditions, such as premature birth and congenital syndromes or chromosomal disorders, whereas older children are most likely to die from external causes, such as traumatic injury.

Fig. 2-2 Major causes of pediatric death in the United States, 1999-2006.

(Data from National Center for Health Statistics.)

For children with CCCs, congenital and chromosomal abnormalities were associated with 5819 (20.3% of 28,527 total) infant and 1087 (4.4%) child deaths, diseases of the nervous system caused 373 (1.3%) infant and 1173 (4.8%) child deaths. Deaths from cancer, which is perhaps the condition most strongly associated with the imagery of palliative care in mind of the public and much of the medical profession, accounted for only 141 (0.5%) infant deaths and 2150 (8.9%) deaths past infancy. A few studies of patients enrolled in pediatric palliative care programs support the evidence of diverse conditions in this population. In a recent study of 8 pediatric palliative care programs in Canada, patients had as their primary diagnosis nervous system disorders (39.1%), cancer (22.1%), or perinatal-onset conditions or congenital anomalies (22.1%).1

Trends and age-specific patterns of mortality

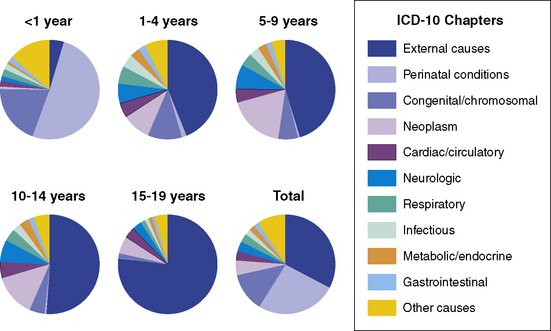

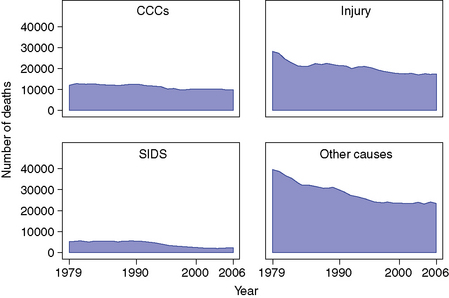

Over the past century, child mortality has been declining for both children suffering from trauma and from complex chronic conditions. Examining U.S. mortality data from 1979 to 2006, the rates of death attributed to CCCs as well as injury, sudden infant death syndrome, and other causes declined substantially (Fig. 2-3), with the corresponding numbers of deaths also declining but less so since 2000 (Fig. 2-4).

Fig. 2-3 Trends in the rates of pediatric death by causes, 1979-2006.

(Data from National Center for Health Statistics.)

Fig. 2-4 Trends in the number of pediatric death by causes, 1979-2006.

(Data from National Center for Health Statistics.)

One published study focused on the interval between 1979 and 1997, when the annual death rate due to non-cancer and cancer-related CCCs declined for almost every age group (from a 7.1% decline for infants with cancer to a 49.9% decline for 1 to 4 year olds dying from non-cancer CCCs). The one exception to this decline was the mortality attributed to non-cancer CCCs among 20 to 24 year olds for whom the rate of death actually increased by 11.6% over this 18-year interval, which may be due to the longer lifespan of younger children with CCCs dying at later ages.2 For this reason, studies of pediatric deaths and palliative care need to include the experiences of young adults, perhaps into their 20s or 30s, who die from conditions with congenital or childhood-onset.

Symptoms and quality of life

The management of physical and psychological symptoms is of utmost importance in palliative care. Most studies published are on bereaved parents of children with cancer. In one such study, 96 bereaved Australian parents of children with cancer reported that, in the last month of life, 84% of children suffered from at least one physical symptom (pain, fatigue, poor appetite, constipation, dyspnea, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and seizures), with pain, fatigue, and poor appetite the most frequent.3 Nearly half (43%) of children suffered from three or more physical symptoms. Parents also reported that 42% of children had been “more than a little sad,” 38% experienced “little or no fun,” and 21% were “often afraid.” In a Swedish study of 449 bereaved parents of children with cancer, physical fatigue was the most frequently reported symptom (86%) to have a higher or moderate impact on the child’s well-being, with reduced mobility (76%), pain (73%), and decreased appetite (71%) also major concerns.4 In this study, parents were more likely to report anxiety in children older than 9 years of age than in younger children (relative risk [RR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2-2.6) and 16 years of age (RR 2.0, 1.3-2.9). Children also suffered from difficulties in swallowing, depression, reduced mobility, impaired speech, swelling, disturbed sleep due to anxiety, and urinary problems. Problems with breathing during the last day of life, and with loss of motor function in the last week of life, were also reported by 28 bereaved parents whose children had been enrolled in a pediatric hospice program in St. Louis.5 Another study of 65 parents of 52 children reported similar symptoms, which did not differ according to patient gender, disease, or location of death, such as the ICU, elsewhere in hospital, or home.6 A study of bereaved parents of 48 children who died from cancer also cited that their children suffered from anxiety, which was not treated effectively.7 Given the prevalence of symptoms, and the nature of the child’s condition, it is challenging to measure quality of life for children receiving palliative care services, especially using generalized instruments that may not be suitable for this population of children.8 Nevertheless, much remains to be done in improving the treatment of symptoms in this population.

Pharmacologic treatments and other interventions

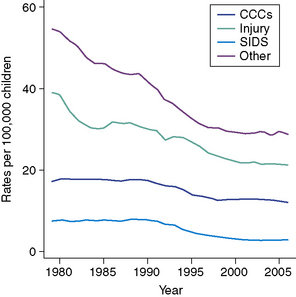

The use of specific medications appears to vary substantially across hospitals and hospices. For instance, in a study of 1466 pediatric oncology patients who died in children’s hospitals, the proportion of patients who received opioids daily during their last week ranged across the hospitals from zero to 90.5%, a variation in practices that did not diminish substantially even after adjustment for patient characteristics (Fig. 2-5).

Medications are only one of many possible interventions used in palliative or hospice care or end of life situations to ameliorate symptoms or improve the quality of life. Much less is known about the epidemiology of other interventions, such as a child’s exposure to complementary and alternative medical (CAM) practices. We do know that in one study of 92 parents of children with cancer in the United States, 49% reported that their children used at least one type of CAM and 20% used herbal remedies, homeopathy, or vitamins in the two months preceding the survey,9 which suggests if any of these children died, some likely continued to receive CAM treatments at the end of life.

Family Systems

The experience of children receiving pediatric palliative care is clearly affected by a variety of specific aspects of their particular families. The structure and membership of a family as well as patterns of family organization and function, such as patterns of communication, cohesion among members, hierarchy, and adaptability to change, influences the care of children with complex chronic conditions.10 Family structure shapes how tasks are divided and roles are assigned in caring for the child, whereby one parent often assumes primary physical care for the patient, and the other parent or other family members manage care of the household and siblings. Structure also dictates how families respond to and regulate their intense emotional reactions to a child’s illness, which influence daily symptom management, soothing the ill child, and making critical end-of-life decisions. Family structure critically affects how care is performed, and is in turn affected by the family’s finances, their social and cultural backgrounds or community, and their religious and spiritual beliefs and practices. To varying degrees, the medical literature provides useful data and knowledge about each of these topics.

Family structure

Families can have many different structures, and families of children with complex chronic conditions are no different. In two-parent married households, research has reported mixed results as to the effects on the marriage. Some studies, such as a case-control study of marital quality in mothers and fathers parenting children with spina bifida, report no difference in marital distress than in parents of healthy children.11 Another study on the same disease reports marital breakdown.12 Other studies, such as one on functioning in parents of children with cancer, suggest that while marital difficulties may occur, positive benefits such as feeling closer as a family and supporting each other may offset the stresses.13 When parents are divorced, communication difficulties may exist, especially when the nonresidential parent has a different opinion about the child’s care than that of the custodial parent.14 Single-parent households have been less frequently studied,15 but some evidence suggests that single mothers of children with cystic fibrosis may have higher stress-related symptoms and that their children may have higher hospitalization rates;16 another study on handicapped children suggests that single mothers have greater difficulty with finances, but also were more flexible in adapting to new family roles and arrangements.17 Step-parents in the home also alter the family structure.18

Siblings add another dimension. While the national percentage of children with complex chronic conditions who have siblings is unknown, meta-analyses investigating the effects of childhood chronic illness on siblings suggests a modest, negative effect on psychological functioning, peer activities, and cognitive development, with lower scores reported by parents than by the siblings themselves.19,20 Recommendations for siblings include providing information about their brother’s or sister’s illness early on, group discussions, and informing school personnel.21

Another aspect of families that we can consider concerns other social and cultural characteristics. Various studies indicate that racial and ethnic minorities may have difficulties with trust and communication with the medical profession, poverty, and different belief systems and family structures.22–25 Religion and spirituality are very important to families, but their impact is not uniform nor prescriptive.26,27

The work of care

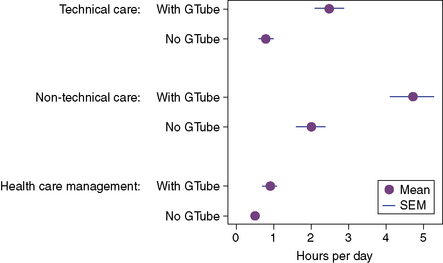

The work of care consists of the effort, labor, and various tasks in which parents and other family members engage in to care for the child with a complex chronic condition and for the family system. Daily tasks include administering medications, feeding and bathing, providing emotional support, and monitoring any changes in the child’s health.28–32 Parents also are responsible for managing their child’s medical care by arranging and bringing their child to appointments and filling out copious amounts of paperwork,33 while creating an environment where their child can have as normal a life as possible.34 These efforts can occupy a great deal of time.35 One study of parents whose children had gastrostomy tubes, compared to parents whose children did not, found parents in the first group devoted more than 7 hours a day to technical and non-technical care of the child compared to 3 hours in the second group (Fig. 2-6).36 How this work is organized, distributed, and completed likely varies across family structures, and some evidence also exists that stronger family function is related to better execution of disease management activities.37–39

Fig. 2-6 Number of hours per day devoted by parents to caring for children with gastrostomy tubes.

(Data abstracted from Heyman MB, Harmatz P, Acree M, Wilson L, Moskowitz JT, Ferrando S, et al. Economic and psychologic costs for maternal caregivers of gastrostomy dependent children. J Pediatr. 2004;145(4):511-516.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree