Chapter 25 Endometriosis and Adenomyosis

Endometriosis

Endometriosis

PATHOGENESIS

SITES OF OCCURRENCE

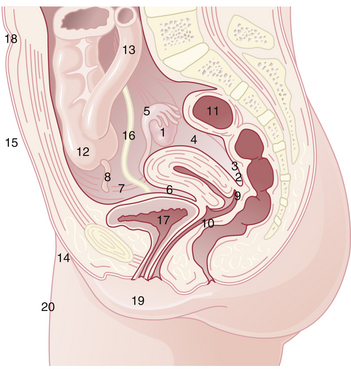

Endometriosis occurs most commonly in the dependent portions of the pelvis. Specifically, implants can be found on the ovaries, the broad ligament, the peritoneal surfaces of the cul-de-sac (including the uterosacral ligaments and posterior cervix), and the rectovaginal septum (Figure 25-1). Quite frequently, the rectosigmoid colon is involved, as is the appendix and the vesicouterine fold of peritoneum. Endometriosis is occasionally seen in laparotomy scars, developing especially after a cesarean delivery or myomectomy when the endometrial cavity has been entered. It is probable that endometrial tissue is seeded into the surgical incision. Two of three women with endometriosis have ovarian involvement.

PATHOLOGY

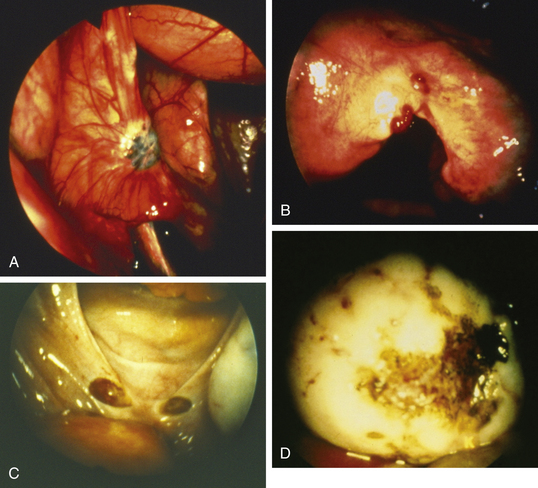

Lesions may be raised and flat with red, black, or brown coloration; fibrotic scarred areas that are yellow or white in hue; or vesicles that are pink, clear, or red (Figure 25-2). The color of the implant is generally determined by its vascularity, the size of the lesion, and the amount of residual sloughed material. Newer implants tend to be red, blood-filled active lesions. Older lesions tend to be much less active hormonally, scarred and blue-gray in color with a puckered appearance. These older inactive lesions have been called the “tattooing of endometriosis.”

STAGING

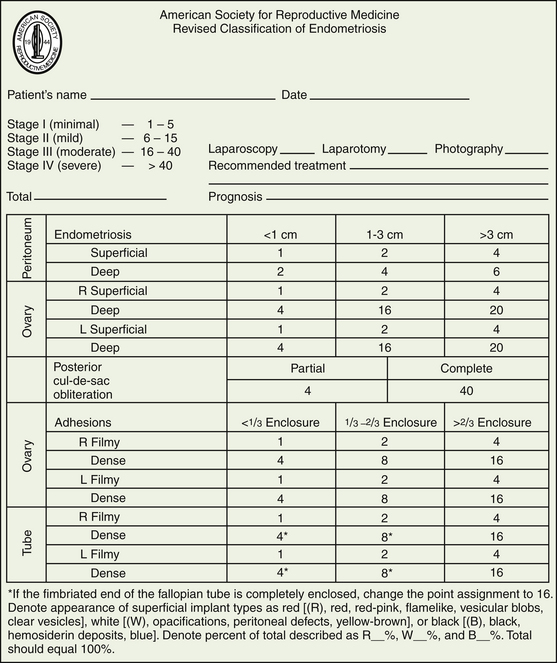

The American Society of Reproductive Medicine employs a staging protocol in an attempt to correlate fertility potential with a quantified stage of endometriosis. This staging, which was initially based on the allocation of points depending on the sites involved and extent of visualized disease (Figure 25-3), was modified to include a description of the color of the lesions and the percentage of surface involved in each lesion type, as well as a more detailed description of any endometrioma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree