CHAPTER 33 Endometriosis

Introduction

Endometriosis is one of the most common benign gynaecological conditions. It is second only to uterine fibroids as the most common reason for major surgical procedures in women under 45 years of age. It has been estimated that it is present in between 10% and 25% of women presenting with gynaecological symptoms in the UK and USA (Tyson 1974). These figures are based on the findings of patients who have undergone laparoscopy for diagnostic indications, such as pelvic pain or infertility, or in patients undergoing laparotomy. Although it is such a widespread condition, it is true to say that there is limited understanding regarding its aetiology and pathogenesis, and the condition still arouses much controversy with regard to its diagnosis, treatment and management. Endometriosis varies in severity from minimal disease with a few peritoneal implants to severe disease producing adhesions, deep infiltrating lesions and involvement with ovarian cyst formation.

Prevalence

No racial differences in the incidence of the disease have been found, except for Japanese women who have been reported to have twice the incidence of Caucasian women (Miyazawa 1976).

The exact prevalence of endometriosis is unknown since precise diagnosis depends on observation of implants, predominantly at the time of laparoscopy or laparotomy. Until simple non-invasive screening tests are developed, the true prevalence will remain unknown. Current prevalence therefore depends upon identification in women who are either symptomatic or undergoing various operative procedures. The incidence is markedly variable as the data in Table 33.1 show, but the prevalence of endometriosis in the reproductive years is estimated to be approximately 10% (Eskenazi and Warner 1997). Endometriosis commonly affects women during their childbearing years. In the main, this is reflected in deleterious sexual, reproductive and social consequences as a result of its associated painful symptoms and often associated infertility. Symptomatology may extend over several decades of a patient’s life because of its often late diagnosis and the recurrent nature of the disease. For individual patients and healthcare systems, it represents a major call upon resource use.

Table 33.1 Prevalence of endometriosis through various presentations

| Presentation | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| Unexplained infertility | 70–80* |

| Infertile women (all causes) | 15–20* |

| At diagnostic laparoscopy | 0–53† |

| At treatment laparoscopy | 0.1–50† |

| Women undergoing sterilization | 2‡ |

| In women with diagnosed first-degree relatives | 7§ |

* Source: Kistner RW 1977 In: Sciarra J (ed) Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 1. Harper and Row, London.

† Source: Houston DE 1984 Epidemiology Reviews 6: 167–191.

‡ Source: Strathy JH, Molgaard GA, Coulam CB, Molton LJ III 1982 Fertility and Sterility 38: 667–672.

§ Source: Simpson JL, Elias S, Malinak LR, Buttram VC Jr 1980 American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 137: 327–331.

Pathogenesis

Transformation of coelomic epithelium

This theory, first described by Meyer (1919), postulated the possibility of differentiation by metaplasia towards an endometrial-like tissue of the original coelomic membrane following prolonged irritation and oestrogen stimulation. It is proposed that these adult cells undergo dedifferentiation back to their primitive origin and then transform to endometrial cells. If this theory is correct, metaplasia should occur wherever coelomic membranes are present. This theory has many attractions which could explain the occurrence of endometriosis in nearly all the ectopic sites in the presence of aberrant Müllerian cells. What induces this transformation — whether it is hormonal stimuli, inflammatory irritation or other processes — is uncertain. If coelomic metaplasia is similar to metaplasia elsewhere, the frequency of the disorder should increase with advancing age. The clinical pattern of endometriosis is distinctly different from this, with an abrupt halt in the disease with the cessation of menses at the menopause and reduced oestrogen production, thus raising some questions over this theory.

Menstrual regurgitation and implantation (metastatic theory)

As early as 1927, Sampson proposed the metastatic theory, postulating that retrograde menstrual flow transported desquamated endometrial fragments through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity (Sampson 1927). Once there, the still viable cells subsequently implanted and began growth and invasion. In support of this theory, experimental endometriosis has been induced in animals with replacement of menstrual fluid or endometrial tissue in the peritoneal cavity. Supporting this theory in humans is the finding that endometriosis is commonly found in young girls with associated abnormalities in the genital tract causing obstruction to the outflow of menstrual fluid (Schifrin et al 1973). Halme et al (1984) observed bloody fluid at the time of menstruation in the pelvis during laparoscopic assessment, but as this finding occurs in up to 90% of all women, it is regarded as a physiological phenomenon. The high incidence of retrograde menstruation suggests that this phenomenon alone does not give rise to endometriosis, but that some other factor(s) must be involved in development of the disease. These factors could include some alteration in the (uterine) endometrium, altered immune response to retrograde menstruation (hence failure to clear the peritoneal cavity of debris efficiently), or a more favourable peritoneal environment which may stimulate the growth and implantation of ectopic endometrium within the peritoneal cavity itself.

Genetic and immunological factors

Many studies have indicated that there may be a genetic factor related to endometriosis since the disease is more prevalent in certain families. It has been shown that women with an affected first-degree relative have a seven times higher risk of developing endometriosis, which may be severe (Simpson et al 1980, Halme et al 1986). Endometriosis is also more common in monozygotic twin sisters than dizygotic twins, but no association was found with specifically identified tissue types (Simpson et al 1984). Whilst Dmowski et al (1981) demonstrated a decreased cellular immunity to endometriotic tissue in women with endometriosis, no clinically significant immune system abnormality has been observed in women with the disease; hence, the precise genetic or immune components increasing an individual’s potential to develop this disorder are yet to be defined.

Endometrial disease theory

Many view the superficial implants as ‘physiological’ lesions which may regress spontaneously. Deep infiltrating lesions and ovarian endometriotic cysts are pathological and arise from cells that have undergone somatic mutations. Such mutations may have been produced by environmental factors (e.g. pollutants, dioxins). These abnormal cells then develop into a ‘benign tumour’ consisting of endometriotic glands and stroma. For a review on environmental factors in the aetiology of endometriosis, the reader is directed to Missmer and Mohllagee (2008).

Further support of the above theory stems from biochemical differences demonstrated in the endometrium in patients with and without endometriosis (Guidice and Kao 2004). These include differences in the expression of metalloproteinases, tumour susceptibility genes and angiogenic factors. Such changes may allow certain types of retrograde endometrial fragments to implant more readily than others, and this may be due to an underlying inherited genetic tendency.

Conclusion

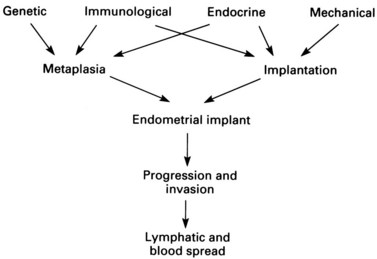

The conclusion reached from the above theories is that pelvic endometriosis is probably a consequence of transplantation of viable endometrial cells regurgitated at the time of menstruation from the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity. In addition, transport of endometrial cells may occur by other routes (some iatrogenic). It is unclear whether endometriotic implants are derived from in-situ pluripotential cells generated by metastatic seeding, but it is known that endocrine and immunological factors allow growth and spread within the pelvis and neighbouring organs. Delayed childbearing, either by choice or infertility, has been implicated as a risk factor for the development of endometriosis. The risk of developing endometriosis also corresponds with cumulative menstruation, menstrual frequency and volume. Women with shorter menstrual cycles of less than 27 days and longer flows (more than 7 days) are twice as likely to develop the disease compared with women with longer cycles and shorter flows. Thus, many components are necessary to allow endometriotic deposits to implant and subsequently grow (Figure 33.1).

Peritoneal Fluid Environment in Endometriosis

Peritoneal macrophages

Normal peritoneal fluid contains approximately 106 cells per ml; 90% are macrophages, and the remainder are lymphocytes and desquamated mesothelial cells. The role of peritoneal macrophages in women with endometriosis has been the source of much interest, and women with endometriosis associated with infertility have been reported to have significantly higher concentrations of macrophages in peritoneal fluid than either fertile women or infertile women without endometriosis. Macrophages in patients with endometriosis appeared to be highly phagocytic against spermatozoa in vitro compared with those from fertile women or infertile women without endometriosis (Muscato et al 1982). In addition, they are also able to survive better in vitro than those from fertile controls (Halme et al 1986). Peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis has also been shown to have a cytotoxic effect on in-vivo cleavage of mouse embryos. These findings on the quantitative and qualitative properties of macrophages in peritoneal fluid may partially explain the mechanisms of infertility in patients with endometriosis.

Prostaglandins and prostanoids

The role of prostaglandins and their metabolites in peritoneal fluid in the pathogenesis and symptomatology of endometriosis is controversial. It has been reported that increased levels of prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) are found in the peritoneal fluid of patients with the disease (Meldrum et al 1977). In addition, increased peritoneal fluid volume and increased concentrations of the prostaglandin metabolites thromboxane B2 and 6-keto PGF2α have been noted. Other investigators have found no increase in either the volume of peritoneal fluid or its concentrations of prostaglandins or metabolites (Rock et al 1982). These conflicting reports may reflect the timing of peritoneal fluid sampling and difficulties in assay measurement of the small quantities of substrates, all of which have very short half-lives.

Presentation

Atypical bleeding patterns are a leading symptom in a variety of gynaecological diseases, but may also characterize patients with endometriosis. Premenstrual spotting and menometrorrhagia are frequently noted. On the other hand, cyclical rectal bleeding or haematuria is pathognomonic of the disease and, although rarely observed (1–2% of cases), these symptoms give strong evidence for bowel or bladder involvement. Painful micturition or defaecation at the time of menstruation may be the first signs of progressing disease. The various symptoms of endometriosis as found in various sites of implantation are shown in Table 33.2.

Table 33.2 Symptoms of endometriosis related to sites of implants

| Symptoms | Site |

|---|---|

| Dysmenorrhoea | Reproductive organs |

| Lower abdominal pain | |

| Pelvic pain | |

| Low back pain | |

| Menstrual irregularity | |

| Rupture/torsion endometrioma | |

| Infertility | |

| Cyclical rectal bleeding | Gastrointestinal tract |

| Tenesmus | |

| Diarrhoea/cyclic constipation | |

| Cyclical haematuria | Urinary tract |

| Dysuria (cyclical) | |

| Ureteric obstruction | |

| Cyclical haemoptysis | Lungs |

| Cyclical pain and bleeding | Surgical scars/umbilicus |

| Cyclical pain and swelling | Limbs |

Correlation of symptoms and severity of endometriosis

The frequencies of the more common symptoms in endometriosis patients are summarized in Table 33.3. Whilst the symptoms of dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia and pelvic pain can occur with other gynaecological disorders, it is the combination, cyclical and menstrually related component of several symptoms which should alert the clinician to the potential underlying presence of endometriosis. Many women have delayed diagnosis of their condition, which may mean that it has progressed to a more extensive and potentially less reversible or curable stage at the time of diagnosis.

Table 33.3 Frequency of the more common symptoms in endometriosis patients

| Symptom | Likely frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Dysmenorrhoea | 60–80 |

| Pelvic pain | 30–50 |

| Infertility | 30–40 |

| Dyspareunia | 25–40 |

| Menstrual irregularities | 10–20 |

| Cyclical dysuria/haematuria | 1–2 |

| Dyschezia | 1–2 |

| Rectal bleeding (cyclic) | <1 |

There appears to be little correlation between sites involved in endometriosis and symptoms. Various ‘types’ of symptoms can, however, be related to some degree to the system involved (see Table 33.2). However, these do not always correlate with the anatomy and type of pain innervation of the pelvis (for review, see MacLaverty and Shaw 1995).

Deeply infiltrating endometriosis is very strongly associated with the presence and severity of pelvic pain. In addition, superficial non-pigmented endometriosis has the capacity to produce more prostaglandin F (PGF) than pigmented classic powder burn lesions. PGF is implicated in pain causation (Vernon et al 1986). Thus, in the early, less florid stages before it has become destructive and more easily recognized, endometriosis may be producing large quantities of PGF and hence possesses greater potential to increase the severity of pain. The type of pain may alter with disease progression, with constant pain and exacerbation at the menses initially in the disease, and pain later becoming continuous due to scar formation and organ fixity.

Endometriosis and Infertility

Endometriosis was one of the most frequently made diagnoses in couples undergoing infertility investigation, when routine use of laparoscopy for investigation of such couples was employed, in past years. The assumption was made that endometriotic implants are responsible for the patient’s inability to conceive. Estimates of the incidence of endometriosis in the general population of reproductive age vary between 2% and 10%. From retrospective studies in infertile patients, the incidence has been reported as being between 20% and 40% (Mahmood and Templeton 1990). This increased incidence in infertile patients has led many clinicians to consider the endometriotic implants to be responsible, in some way, for the associated infertility. The question is how, and a number of suggested mechanisms have been reported. These are summarized in Table 33.4. For the majority of these potential causes, there are few or no consistent data to provide a sustainable explanation. Thus, the nature of the relationship between mild endometriosis and infertility remains unresolved.

Table 33.4 Possible mechanisms of causation of infertility with mild endometriosis

| Problem area | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Ovarian function | |

| Luteolysis caused by prostaglandin F2α | |

| Oocyte maturation defects | |

| Coital function | Dyspareunia causing reduced penetration and coital frequency |

| Tubal function | Alterations in tubal and cilial motility by prostaglandins |

| Impaired fimbrial oocyte pick-up | |

| Sperm function | Phagocytosis by macrophages |

| Inactivation by antibodies | |

| Endometrium | Interference by endometrial antibodies |

| Luteal-phase deficiency | |

| Early pregnancy failure | Increased early abortion |

| Prostaglandin induced or immune reaction |

Although there may be some debate about the role of filmy peritubal or periovarian adhesions in infertility, it is accepted that with increasing severity of endometriosis, adhesions become more common and the chances of a natural conception decrease. The majority of specialists would divide such adhesions if found at laparoscopy and if appropriate consent had been obtained, although laparoscopy is no longer routinely undertaken in asymptomatic infertile women. Evidence that the treatment of endometriosis benefits fertility would provide proof that endometriosis is linked with infertility. Historically, many studies have utilized ovarian-suppression treatments with progestogens, danazol and/or gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues in the hope of treating endometriosis and enhancing fertility. The majority of these patients had minimal or mild endometriosis (see later for classification). These studies show that 3–6 months of medication prevents fertility during treatment, but does not increase pregnancy rates following treatment cessation. Meta-analysis showed no difference in pregnancy rate between ovarian suppression and no treatment (relative risk 0.98; confidence interval 0.81–1.15) (Hughes et al 1993, Adamson and Pasta 1994). There was no difference among different ovarian-suppression agents, and the current recommendation is that ovarian suppression in the infertile patient is not justified because of lack of effectiveness on improving conception rates over a conservative approach alone.

Laparoscopic surgical destruction, excision or laser ablation of endometriotic deposits has become popular in recent years and is helpful in pain management of selective endometriosis patients (see later). However, its role in patients with endometriosis and infertility without tubo-ovarian adhesion, endometriomas or other pathology is in question. The ENDOCAN randomized trial from Canada showed a higher pregnancy rate at 9 months in patients who had undergone surgical destruction of endometriotic deposits (and any adhesions present) compared with the control (no treatment) arm (37.5% vs 22.5%). The number needed to treat to create a pregnancy was 7.7 (Marcoux et al 1997). However, a smaller, prospective randomized controlled trial from Italy did not show any difference in pregnancy rates between the treatment and control groups (19.6% vs 22.2%) (Parazzinni 1999). There is a need for more large randomized controlled trials to investigate the role of surgery in such patients.

Conclusions

To date, it is not known how mild endometriosis (without tubo-ovarian disease or adhesions) causes infertility, but it is recognized that such patients have a reduced fecundity rate. Until the underlying cause (if any) is found and appropriate corrective therapies are available, such asymptomatic patients are best treated along the lines of unexplained infertile couples (see Chapters 20 and 22) with treatment options based on age and duration of infertility.