Chapter 60 Endocrinology

DIABETES MELLITUS

EVALUATION

How Do Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Differ?

Distinguishing type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes is important and may present a diagnostic dilemma in children. Although there is a genetic component to type 1 diabetes, a family history of diabetes is positive in only 1 of 10 patients. By contrast, the family history in type 2 diabetes is usually more prominent. Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes cause polyuria and polydipsia. Type 1 diabetes has mainly nonspecific physical findings, including dehydration, weight loss, and, rarely, growth failure. Type 2 diabetes is strongly associated with obesity as a component of the metabolic syndrome and may have additional findings, including acanthosis nigricans, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and, in females, polycystic ovary syndrome. Table 60-1 lists the features of both types of diabetes.

Table 60-1 Characteristics of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

| Characteristics | Type 1 Diabetes | Type 2 Diabetes |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | All ages | Puberty |

| Gender | Male = female | Female > male |

| Highest prevalence | Caucasians | African-Americans, Latinos, Native Americans |

| Symptom onset | Rapid | Progressive |

| Diagnosis on routine physical examination | Uncommon | Common |

| Hx of polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss | Common | Less common |

| FHx of diabetes | Infrequent | Frequent |

| FHx of autoimmune disease, such as hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism | More frequent | Less frequent |

| Obesity | Less common | Very common |

| Acanthosis nigricans | Rare | Common |

| DKA at onset | Common | Rare |

| Ketones in urine | Common | Rare to absent |

| Islet cell autoantibodies | Present | Absent |

DKA, Diabetic ketoacidosis; FHx, family history; Hx, history.

How Is Blood Glucose Used to Diagnose Diabetes?

The following blood glucose findings are diagnostic of diabetes:

• Casual blood glucose greater than 200 mg/dl along with symptoms of diabetes (“casual” = random, without regard to time since last meal)

• Fasting glucose above 126 mg/dl

• Blood glucose greater than 200 mg/dl, 2 hours after a glucose load during an oral glucose tolerance test

TREATMENT

What Are the Guidelines for Blood Glucose Control?

The principal goal of home blood glucose monitoring is to maintain blood glucose within the age-specific target range. In practice, tight blood glucose control is difficult, and most patients have frequent excursions both below and above the target range (Table 60-2). Effectiveness of the treatment regimen and adherence by the patient are assessed by regular blood glucose determinations. All blood test results should be recorded in a log that is reviewed at each clinic visit so that insulin or oral medication doses may be adjusted. Approximately every 3 months, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should be measured to assess chronic blood glucose control.

Table 60-2 Target Ranges for Blood Glucose Control

| Age | Blood Glucose (mg/dl) |

|---|---|

| Infants and preschool children | 100-200 |

| School-aged children and adolescents | 70-150 |

How Is Insulin Used to Treat Type 1 Diabetes?

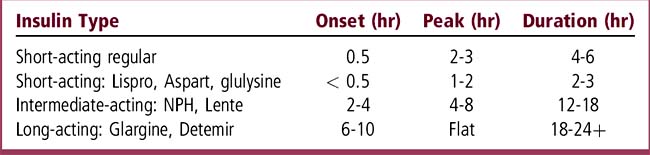

Treatment depends on whether the patient has type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes. On occasion, the distinction cannot be made and it is usually safest to begin treatment with insulin. Type 1 diabetes is always treated with insulin. Short-acting and long-acting insulins are typically injected alone or in combinations three or more times daily. You must be aware of the speed of onset and the duration of action of each commonly used type of insulin (Table 60-3). Increasing numbers of adolescents and young children are now using external insulin pumps for continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. The pump delivers short-acting insulin at a basal rate during the day and night and as a bolus whenever needed to correspond to a meal. Patients learn to match the amount of insulin to the carbohydrate content of the food they are about to eat.

What Medications Are Used for Type 2 Diabetes?

Type 2 diabetes is treated with oral medications and sometimes with insulin. Commonly used oral hypoglycemic agents and their mechanisms of action are listed in Table 60-4.

Table 60-4 Oral Hypoglycemic Agents

| Mechanism of Action | Examples |

|---|---|

| Insulin secretogogues | Sulfonylureas, meglitinide |

| Insulin sensitizers | Metformin, thiazolidinediones |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors | Acarbose, miglitol |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree