11

Emotional and behavioural problems

Chapter map

Children are unable to express their thoughts and feelings as easily as adults. Emotional disturbances are often expressed either through change in behaviour or through physical symptoms such as aches and pains. The child is part of a family, and problems elsewhere in the family may manifest as emotional and behavioural problems in the child. True psychiatric illness is rare in children. After reviewing attachment and parenting, which are foundational to children’s mental health, this chapter discusses types and causes of problems. This provides the basis for management, generally and in regard to specific disorders.

11.2 Types of emotional and behavioural problems

11.3 Causes of emotional and behavioural problems

11.3.3 Child–family interaction

11.4.1 General approach to management of behavioural problems

11.4.2 General approach to management of stress-related (psychosomatic) symptoms

11.5.1 Stress-related symptoms

11.5.2 Behavioural and sleep-related

11.5.3 Severe behavioural disorders

11.5.3.1 Autistic spectrum disorders

11.5.3.2 Attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- They affect 5–10% of children in rural areas, 10–20% of children in urban areas.

- Up to one-third of children presenting to their GP or paediatric services have a psychological component to their presentation.

11.1 Attachment

Attachment describes the special relationship that a young child has with his main carers (usually the parents). Young children need to develop at least one secure attachment. A child may have several ‘attachment figures’, but for young children the most intense attachment is usually to the mother. Within this attachment relationship are a typical sequence of behaviours that occur again and again:

- The child has a need, and expresses it (care-eliciting). For example, a baby cries when he is hungry, or a young child runs to her parent when she is frightened.

- The parent recognizes the need, and responds (care-giving). The baby is fed, the young child comforted.

- The child settles, his need met, and his internal balance restored.

Over the early years of life, this repeated sequence builds into the child a model of their world that affects future relationships. With ‘good enough’ parenting, a secure attachment forms, and the model includes fundamental concepts such as ‘I am loveable’, ‘People will be there for me’ and ‘People can be trusted’. If care-giving is inconsistent, or even abusive, then the attachment is insecure or ambivalent, and the child’s internal model is distorted. Such children find it difficult to form intimate, trusting relationships later on.

Stranger anxiety builds from about 6 months, is maximal at around a year, and then slowly recedes as children reach school age (this is why young children need to be examined close to their parents). A child who has not formed secure attachments may be either suspicious and hostile or overly familiar with strangers.

11.1.1 Good enough parenting

No parent is perfect, and most struggle at times with the challenges of bringing up children. Children need a certain level of care to grow and develop both physically and emotionally, and to meet their attachment needs. Bonding describes the special relationship that the parents (especially the mother) have with their young child. This bond allows them to love, give to, understand, forgive and cherish their child through good and bad times. Mothers do not necessarily love their baby at first; it may take several weeks. Ideally, parents should be alone with their new baby in quiet, happy and untroubled surroundings, but separation, for example by neonatal illness, does not prevent normal attachment.

- Praise > criticism

- Rewards > punishment

- Set limits

- Constancy

- Non-victimization

- Non-oppressive

- Encourage learning and exploration

- Encourage independence

- Security within a family home.

RESOURCE Parenting ‘handbooks’

RESOURCE Parenting ‘handbooks’- Toddler Taming by Christopher Green is full of sensible advice for the first 4 years (e.g. see the chapter on sleep).

- How to Talk So Kids Will Listen and Listen So Kids Will Talk by Faber and Mazlish – does what it says!

- The Incredible Years by Webster-Stratton is the basis for a popular parenting course (see www.incredibleyears.com)

11.2 Types of emotional and behavioural problems

Since the causes and management of these problems have much in common, the next part of this chapter will focus on a general approach. Specific problems will then be discussed in more detail.

| Infants and pre- school children | Older children | |

| Behavioural | Behavioural | Stress-related |

| Tantrums | Defiant | Headaches |

| Sleep problems | Impulsive | Abdominal |

| Feeding difficulties | Attention deficit | pains |

| Crying babies | Lying | Vomiting |

| Breath-holding | Stealing | Wetting |

| attacks | Truancy | Soiling |

| Tics | ||

11.3 Causes of emotional and behavioural problems

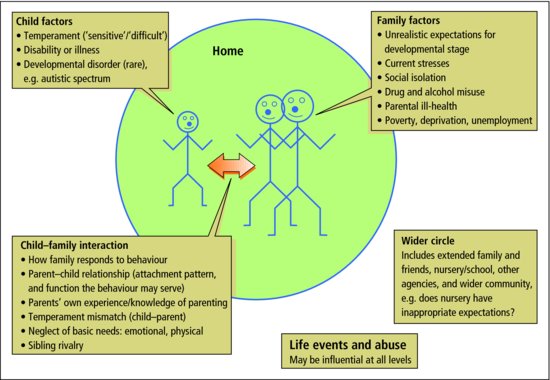

There are many factors which lead to these problems (Figure 11.1). Children’s symptoms vary greatly and there is often no clear relationship between particular behavioural problems and specific causes. Most often it is to do with the child’s interactions or relationships with important people around them. Many problems are exaggerations of normal behaviour, unintentionally maintained through the way they are being handled, especially if there are inconsistencies between parents.

11.3.1 Child factors

The form that an emotional disturbance takes will depend in part upon the cause and in part upon the child’s personality and the family patterns of response to stress. Some children are of a buoyant temperament and can ride almost any crisis; others are sensitive plants and bow before every emotional breeze. The way parents respond to the problem may inadvertently exacerbate or perpetuate these problems. Stress may present as headache, tempers or abdominal pain in different children. The toddler who feels challenged by the arrival of a new baby may resort to infantile behaviour.

11.3.2 Family factors

11.3.2.1 Acute separation and change

The death of a parent or of a much-loved grandparent, emergency admission to hospital, or moving house are examples of acute separations. These are most upsetting to young children around 2–4 years old who are conscious of the separation but unable to understand the reason.

11.3.2.2 Parental discord and separation

All children are conscious of the relationship between their parents and will be aware of any deterioration. Parents who attempt to get their children to take sides during conflict make this an even more difficult experience.

RESOURCE Children and parental divorce or separation

RESOURCE Children and parental divorce or separation- www.divorceaid.co.uk – this site provides advice, support and information on all aspects of divorce and has useful resources for young children, teenagers as well as for parents.

- www.rcpsych.ac.uk has a useful factsheet (search for ‘divorce’ on their site) as part of their excellent ‘Mental Health and Growing Up’ series.

- www.raisingchildren.net.au is an Australian site – search there for ‘Me and my changing family’, an online book, which offers tips on building healthy relationships after separation. A few items are specific to Australia.

11.3.3 Child–family interaction

11.3.3.1 Inconsistent handling

If a child is permitted something by one parent that is denied by the other, or punished on one occasion and ignored on another, this is likely to lead to behavioural problems. The intelligent child is quick to play off one adult against another, or to achieve her own ends by alarming or distressing the adults around her.

11.3.3.2 Lack of parental time

All children need regular positive attention, especially from their parents. When this is lacking, then the negative attention given for bad behaviour can become enough of a reward to reinforce the behaviour. This can lead to a vicious cycle of more negative attention (e.g. telling off, punishing) leading to worsening behaviour.

11.3.3.3 Sibling rivalry

Most toddlers, and especially first-borns, delight in the new baby, but may resent the time that their mother devotes to it. Aggression is likely to be directed against the mother rather than against the baby. When the new baby is old enough to be mobile and to interfere with the elder sibling’s activities, jealousy will become more obvious. At school age, constant comparisons between siblings with different capabilities and interests can devastate the less clever or the clumsy.

11.3.3.4 Great expectations

Parents naturally want their child to do well, but may form an unrealistic idea of her capabilities or set their hearts on a career which she could never achieve. Although many a child ‘could do better if she tried’, not everyone is destined for an honours degree. If parents constantly nag when she is doing her best, psychological difficulties may follow. Somatization is common (e.g. abdominal pains).

11.3.4 Wider circle

Do not forget to explore the child’s life outside the immediate family. Remember school, nursery and the extended family. All of these may have an impact and offer you insight into problems that are occurring. Although most schools try to minimize bullying, it is still a common and important cause of behavioural problems. Contact with the school or nursery (with the parents’ permission) is often helpful.

11.3.5 Life events and abuse

Sometimes a child is witness to, or involved in, an acutely distressing situation – a road accident, a sudden death or sexual abuse. This may lead to a variety of symptoms such as disturbed behaviour (e.g. night terrors), or to acute physical symptoms (e.g. overbreathing). An event like this may have severe long-term effects.

11.4 Management

11.4.1 General approach to management of behavioural problems

Most behavioural problems in young children respond to a calm and consistent approach that emphasizes the positive. Identify and build on the strengths of the child and family. Encourage parents to work together, and to use distraction and/or change of activity when the problem behaviour is first noticed. Simple explanation helps parents realize that these problems are extremely common and part of normal experience. They do not need to feel there is something fundamentally ‘wrong’ or ‘bad’ about themselves or their child.

11.4.1.1 Strategies

- Positive reinforcement:

- Reward desired behaviours with warmth, praise and small tokens (e.g. stars on a star chart)

- Ignore undesired behaviours

- Reward desired behaviours with warmth, praise and small tokens (e.g. stars on a star chart)

- Time out:

- Child removed from the situation for 3 min

- Breaks a negative cycle

- Calms things

- Child removed from the situation for 3 min

- Promote positive parent–child times:

- Good times when contentious issues are set aside

- Affirmation of the child through gesture (e.g. cuddles)

- Activities enjoyed together (e.g. trips, crafts)

- Good times when contentious issues are set aside

- Set and apply clear limits, where consequences of behaviours are:

- Clearly understood

- Applied consistently, quickly and without argument

- Appropriate in magnitude.

- Clearly understood

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree