Early and skilled resuscitation saves lives. It is essential that all who work in health care are trained to recognize emergencies and to act appropriately. Training needs to be kept up to date.

Early and skilled resuscitation saves lives. It is essential that all who work in health care are trained to recognize emergencies and to act appropriately. Training needs to be kept up to date. RESOURCE

RESOURCE- Visit www.erc.edu, European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010, section 6, Paediatric Life Support (www.cprguidelines.eu/2010/).

- iResus is a free mobile phone app published by the Resuscitation Council UK (but not yet available on all platforms) – provides the key algorithms in an easy-to-access format (www.resus.org.uk/pages/iresusdt.htm).

- Spotting the sick child (www.spottingthesickchild.com) is an excellent UK interactive resource (requires registration) that will help you to improve your skills of assessing ill children. It is worth working through it early in your course. It includes videos and self-testing.

Basic life support (BLS) for children over the age of 1 year is now similar to adult life support. The ERC have stated that if someone is trained only in adult life support, the basic life support techniques should be used in the child. If you are training in paediatrics, you will need to learn paediatric life support and the important differences between the child and adult.

KEY POINTS

KEY POINTS- Children’s lives are saved by recognizing impending or imminent danger, and intervening before terminal collapse

- Cardiac arrest usually occurs at the end of a long sequence of deterioration

- Children seldom collapse because of a primary cardiac event

- The outlook for the child who has a cardiac arrest is very poor

The aim of resuscitation training is to give you a clear systematic approach to treatment of the collapsed child. It is helpful to understand the science and evidence underlying these guidelines. It is equally important to be trained and practise them so that they become automatic if you are faced with such an emergency.

4.1 Basic life support

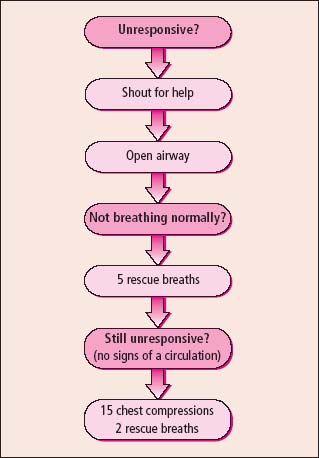

Paediatric BLS is similar to the adult scheme, and follows the ‘ABC approach’. The main difference is that the algorithm starts with five rescue breaths (after determining that the child is unresponsive and calling for help) (Figure 4.1). This is because respiratory arrest is much more common in children than a primary cardiac event.

It is always important to ensure safety for the child, for you and anyone assisting the resuscitation.

Is the child unresponsive? Gently stimulate the child and see if there is a response. If the child responds, attend to other first-aid measures (e.g. pressure on bleeding points), and reassess while help is obtained.

Call for help by asking someone present to call an ambulance, or dial the crash call number when in hospital. Intense anxiety for the child may prevent someone carrying out this simple task. If you are in charge, make sure that it is done. The arrival of skilled help is extremely welcome when someone collapses and you are one of the first people to arrive.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT- Ensure you know the telephone numbers for crash calls in your hospital.

- If the child may have suffered trauma, particularly a road traffic accident, stability of the cervical spine must be maintained. Try to avoid moving the child. Do not shake them. If an airway manoeuvre is required, use chin lift or jaw thrust.

4.1.1 Airway

If the child does not respond, open the airway. This is achieved using head tilt and chin lift. Lift the chin with your finger on the mandible. Do not place your fingers in the soft tissue under the chin as this will compress the airway.

4.1.2 Breathing

Look, listen and feel for breathing. Do not take longer than 10 s doing this. Lean down with your face near to the child and look down their chest. You may be able to hear or feel breathing. If the child is not breathing or if they are breathing irregularly and infrequently, commence resuscitation. Give five rescue breaths.

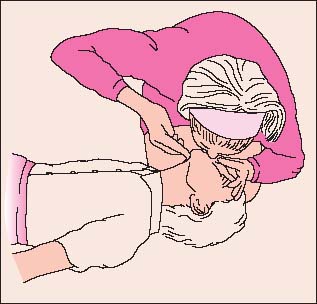

4.1.2.1 Child (Figure 4.2)

With an open airway pinch the nose. Take a deep breath, place your mouth over the child’s mouth and gently but firmly inflate the chest for around 1 s. You will see the chest rise. Then allow the child’s chest to fall as the lungs deflate. Give five breaths.

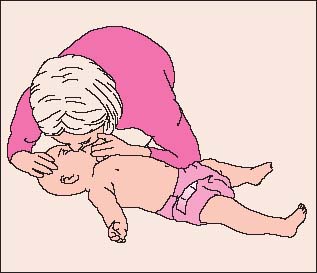

4.1.2.2 Infant (under 1 year) (Figure 4.3)

Ensure the airway is open. Take a deep breath. Cover the baby’s nose and mouth with your mouth. Inflate the chest for 1 s. Allow deflation. Repeat this five times.

If the child or infant’s chest does not rise with inspiration, assess the position of the airway. Consider the possibility of a foreign body (see below).

4.1.3 Circulation

If the child is not recovering, assess circulation. Checking the pulse in an emergency, especially in young children, is quite difficult. In children, use the carotid pulse. In infants the brachial pulse is recommended. Do this quickly in up to 10s. You are also looking for some response to the rescue breaths: if regular breathing or spontaneous movements occur, it is likely that adequate circulation is established.

Commence cardiac massage with chest compression if:

- there are no signs of circulation

- OR a slow pulse of less than 60 with poor perfusion

- OR you are not sure.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTGive 15 compressions and then two breaths and continue with this pattern.

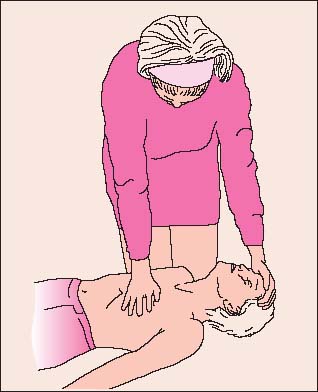

4.1.3.1 Child (Figure 4.4)

The heel of the hand is placed over the lower one-third of the sternum. In bigger children, both hands may be used as in adults.

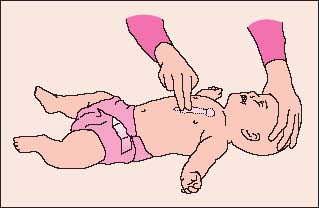

4.1.3.2 Infant (Figure 4.5)

If you are on your own, two fingers are placed over the lower sternum to provide compressions. If there is more than one person, use both hands. The two thumbs are placed on the lower sternum pointing towards the infant’s head. The fingers of the hands encircle the chest.

Continue resuscitation until the child recovers or a more experienced person arrives and is able to decide what is best. If you are on your own, it is recommended to give 1 min of CPR and then go for help.

4.2 Recognition of impending or imminent collapse

There are two main mechanisms of collapse in children and infants. These are respiratory failure and shock. Each has many causes. Early recognition of a child’s worsening condition will allow the team to intervene before collapse occurs. The younger the child, the more quickly he will deteriorate. It can be very difficult to predict these problems in young infants.

This section describes the progress from respiratory distress to failure and the evolution of shock. In many conditions, both occur together.

4.2.1 Respiratory distress and failure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree