5.1 Emergencies

causes and assessment

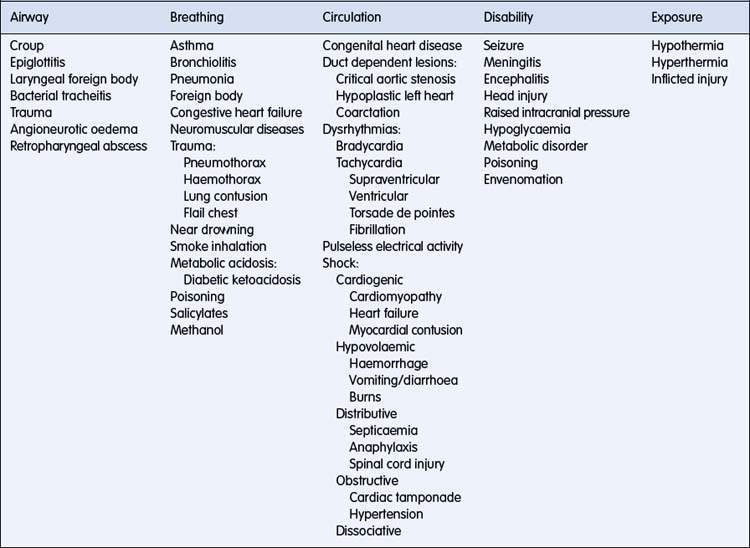

There are many causes of collapse leading to the need for emergency medical intervention in the child. Table 5.1.1 lists some of the causes of common paediatric emergencies.

In approaching the critically ill child, the diagnosis is of secondary importance to:

The resuscitation measures required and management of the collapsed child are described in detail in Chapter 5.2.

The primary assessment

Breathing

Thus, halving the radius increases the resistance very significantly.

Effort of breathing

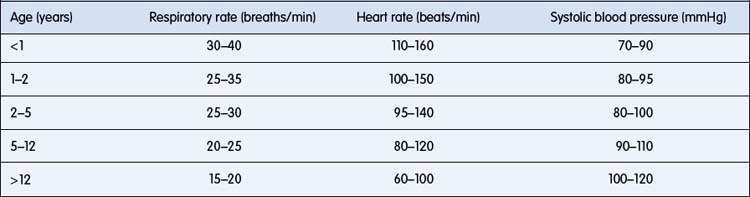

Respiratory rate is age-dependent (Table 5.1.2). Tachypnoea is an early response to respiratory failure. Increased depth of respiration may occur later as respiratory failure progresses. However, it should be noted that tachypnoea does not always have a respiratory cause and may occur in response, for example, to metabolic acidosis. As the intercostal muscles and diaphragm increase their contraction, intercostal and subcostal recession develop. In the infant, sternal retraction may also occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree