Chapter 24 Ectopic Pregnancy

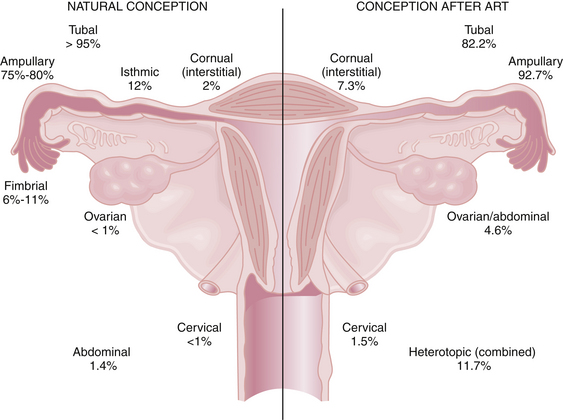

An ectopic pregnancy is a gestation that implants outside the endometrial cavity. Despite recent advances in earlier detection, it continues to represent a serious hazard to women’s health and their future reproductive potential. An ectopic pregnancy is estimated to occur in 1 of every 80 spontaneously conceived pregnancies. More than 95% of ectopic pregnancies implant in various anatomic segments of the fallopian tube, including the ampullary (75% to 80%), isthmic (12%), infundibular and fimbrial (6% to 11%), and interstitial (2%). Other, less common sites of ectopic implantation are the ovary, uterine cervix, and a rudimentary uterine horn. Rarely, an ectopic pregnancy may be intraligamentous or in the peritoneal cavity (abdominal pregnancy). With in vitro fertilization (IVF) and other assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), the risk for ectopic pregnancy increases substantially, and the location of those ectopic implantations changes (Figure 24-1). Importantly, the risk for heterotropic implantations (one intrauterine and one ectopic) may rise to 1 in 100 with IVF. Other risk factors for an ectopic pregnancy include a history of a previous ectopic pregnancy, a pregnancy after tubal ligation or with an intrauterine device (IUD) in place, and a history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

Epidemiology and Etiology

Epidemiology and Etiology

The etiology of ectopic pregnancy is not always clear but often is associated with known risk factors (Box 24-1). As many as half of cases result from an alteration of tubal transport mechanisms because of damage to the ciliated surface of the endosalpinx caused by infections, such as chlamydia and gonorrhea. Other etiologies include delayed fertilization, possible transmigration of the oocyte to the contralateral tube, and slowed tubal transport, which delays passage of the morula to the endometrial cavity. Chromosomal abnormalities of the fetus are not a cause of ectopic pregnancy.

Symptoms and Clinical Diagnosis of Ectopic Tubal Pregnancy

Symptoms and Clinical Diagnosis of Ectopic Tubal Pregnancy

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Many gynecologic and nongynecologic disorders have symptoms in common with ectopic pregnancy and are listed in Box 24-2. A diagnostic algorithm for ectopic pregnancy is illustrated in Figure 24-2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Natural History of Untreated Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy

Natural History of Untreated Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy