51 Disorders of White Blood Cells

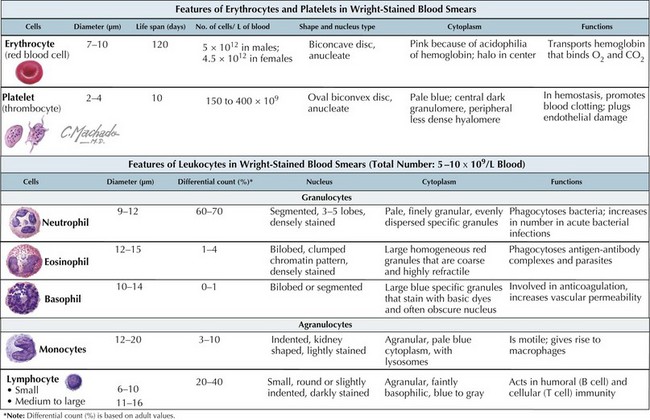

White blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, are an integral part of the host immune system. Their microscopic appearance after Wright-staining categorizes them as either granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils) or agranulocytes (monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes). Each WBC has a specific function within the immune system (Figure 51-1).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

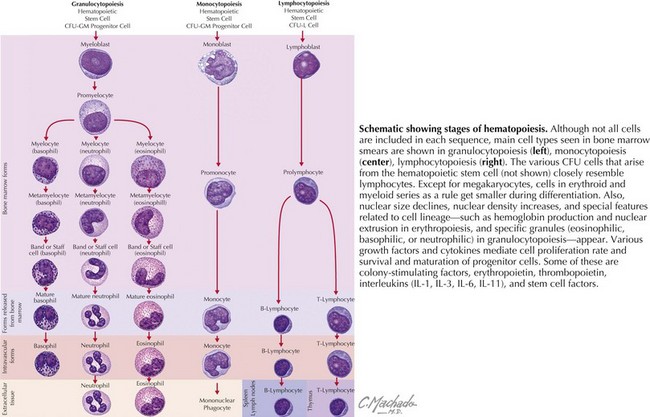

WBCs derive from hematopoietic progenitor cells in the bone marrow (Figure 51-2). Their maturation is induced by colony-stimulating factors.

This chapter focuses on congenital and acquired neutrophil disorders with a brief discussion regarding disorders of eosinophils, basophils, and monocytes. Disorders of lymphocytes, part of the body’s acquired (adaptive) immunity, are discussed in the immunology section (see Chapter 21).

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Congenital Disorders of Neutrophils

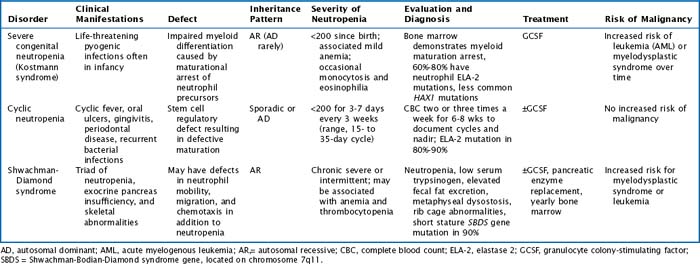

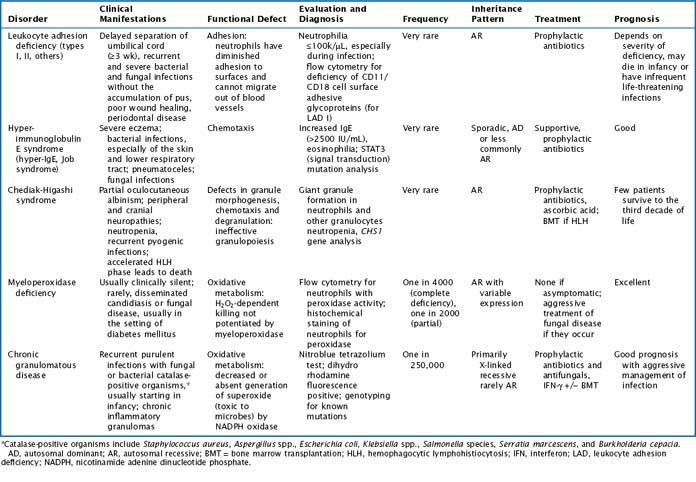

There are multiple congenital neutropenias that are being further categorized as knowledge of the genetic basis of disease improves (Tables 51-1 and 51-2). These congenital disorders are exceedingly rare.

Table 51-2 Additional Congenital Disorders Associated with Neutropenia

| Disorder | Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Cartilage-hair hypoplasia | Short limbs, dwarfism, abnormally fine hair |

| Myelokathexis with dysmyelopoiesis | Marrow retention of neutrophils, recurrent bronchopulmonary infections |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | Bone marrow failure syndrome; dystrophic changes in nails, skin (hyperpigmentation), and mucous membranes (leukoplakia) |

| Fanconi anemia | Bone marrow failure syndrome; GU and skeletal abnormalities, increased chromosome fragility |

| Organic acidemias (propionic, methylmalonic) | Initially well at birth, then toxic encephalopathy |

| Osteopetrosis | Defective bone turnover with resultant hematopoietic insufficiency and bone fragility |

| Reticular dysgenesis (congenital aleukocytosis) | Absent WBC, hypogammaglobulinemia, thymic hypoplasia, severe infection and death in infancy |

| Immunodeficiencies (severe combined immunodeficiency, common variable immunodeficiency, hyper-IgM) | Frequent infections, failure to thrive, hepatosplenomegaly |

| Glycogen storage disease type 1b (von Gierke disease) and other inborn errors of metabolism | Neutropenia and functional neutrophil defect, hepatosplenomegaly |

GU, genitourinary; WBC, white blood cell.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree