103 Disorders of the Gastrointestinal System

Intestinal Obstruction

Clinical Presentation

Subtle differences in presentation can suggest the location of the obstruction along the alimentary tract (Table 103-1). These unique features are highlighted below as each disorder is discussed.

Table 103-1 Localizing Features of Intestinal Obstruction

| Sign or Finding | Proximal or Distal | Specific Site (When Applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| Nonbilious vomiting | Proximal | Proximal to the ampulla of Vater |

| Bilious vomiting | Proximal or distal | Distal to the ampulla of Vater |

| Scaphoid abdomen | Proximal | Often preduodenal |

| Distended abdomen | Distal | |

| Maternal polyhydramnios | Proximal |

Esophageal Atresia

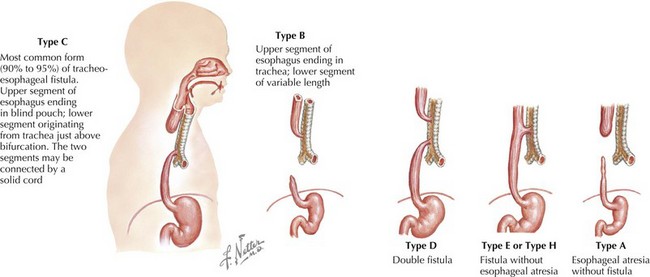

The esophagus can be obstructed in the form of esophageal atresia (EA), which is caused by a failure of separation of the esophagus from the trachea during normal development. Pure EA is rare and often coexists with tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). A standard classification scheme describes the relationship between the atresia and the coexistent TEF (Figure 103-1). The most common combination is EA with distal TEF (type C). The most difficult to recognize and diagnose is “H-type,” which refers to isolated TEF without EA.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree