107 Disorders of the Esophagus

Developmental Anomalies

Etiology and Pathogenesis

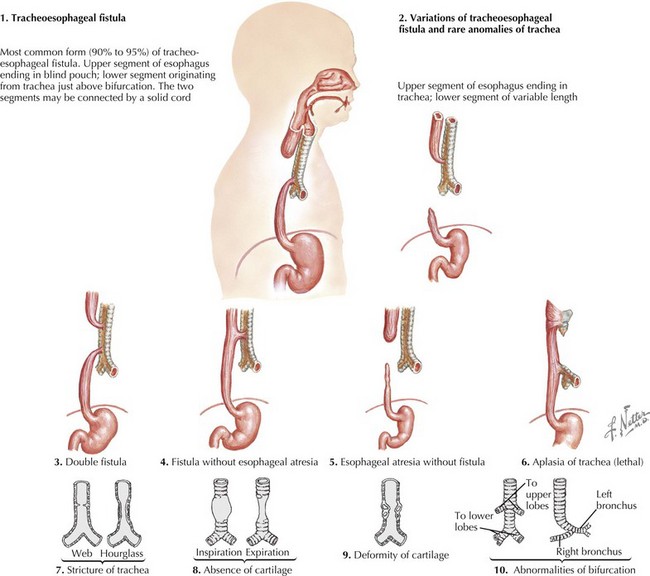

The esophagus forms from a small ventral diverticulum of the embryonic foregut. This diverticulum separates into the esophagus and trachea around the fourth gestational week of fetal development. Anomalies can occur with abnormalities in any step in esophageal formation and development. One of the most common anomalies is TEF with or without atresia. This occurs when there is a disruption in the elongation and separation of the trachea from the esophagus. There are five types of TEF. The most common is type C in which there is atresia of the proximal esophagus with a fistula from the trachea to the distal esophagus (Figure 107-1). Other categories of TEF, in descending frequency, include isolated esophageal atresia without TEF, isolated TEF, esophageal atresia with proximal TEF, and esophageal atresia with proximal and distal TEF.

Motility Disorders of The Esophagus

Evaluation

Achalasia

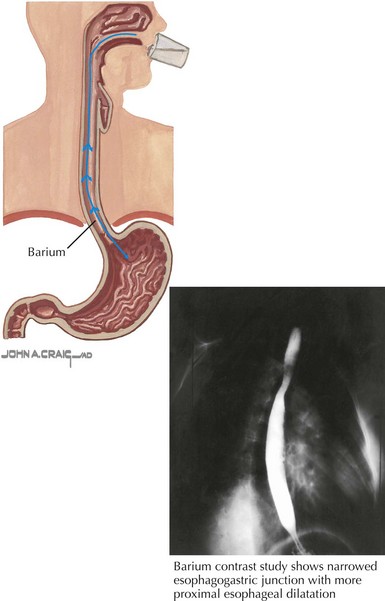

Chest radiograph may show widening of the mediastinum, loss of the gastric air bubble, or an esophageal air-fluid level. Barium swallow will show impaired contrast movement, abnormal peristalsis, and tapering of the distal esophagus known as the “bird’s beak” sign (Figure 107-2). Endoscopy should always be performed and often shows esophageal dilatation, erythema, and ulceration from stasis. Esophageal manometry assesses LES pressures and function in addition to esophageal contraction and motor pattern. In achalasia, manometry shows increased lower esophageal pressure, abnormal peristalsis, and elevated intraesophageal pressures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree