Chapter 10 Diseases of the Cervix

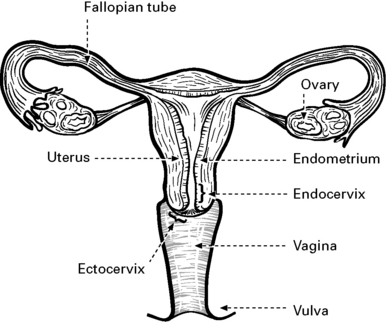

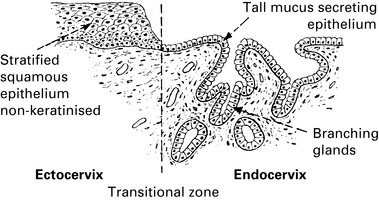

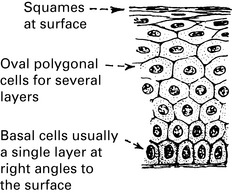

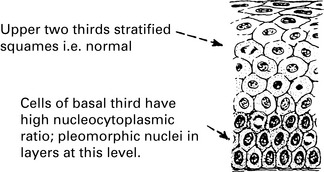

Normal cervical epithelium

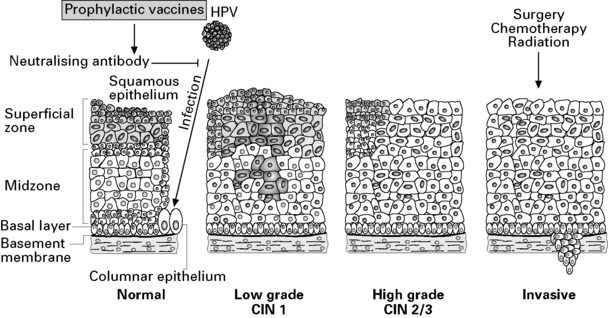

The role of human papilloma virus in cervical disease

Screening for cervical cancer

Screening process

The Cervical Smear

In Scotland, the current cervical screening programme includes the following:

– A national electronic database records and monitors the cervical smear process from the point of invitation to the completion of a colposcopic assessment. This is the Scottish Cervical Call-Recall System (SCCRS).

An abnormal smear is usually an indication for colposcopy (see p. 179).

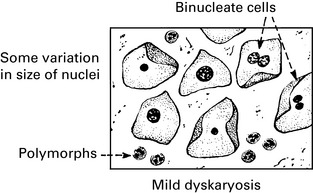

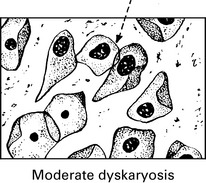

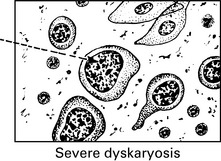

Cervical Smears

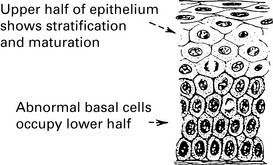

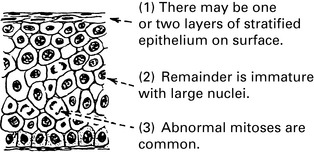

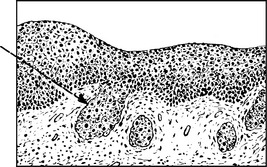

Premalignant and malignant cervical disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree