Chapter 180 Diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae)

Clinical Manifestations

Respiratory Tract Diphtheria

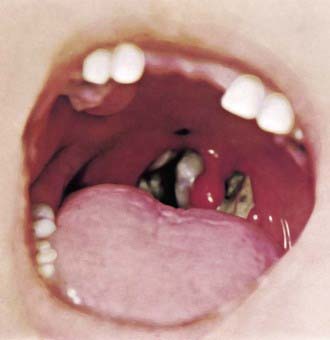

In a classic description of 1,400 cases of diphtheria in California (1954), the primary focus of infection was the tonsils or pharynx (94%), with the nose and larynx the next 2 most common sites. After an average incubation period of 2-4 days, local signs and symptoms of inflammation develop. Infection of the anterior nares is more common among infants and causes serosanguineous, purulent, erosive rhinitis with membrane formation. Shallow ulceration of the external nares and upper lip is characteristic. In tonsillar and pharyngeal diphtheria, sore throat is the universal early symptom: Only half of patients have fever, and fewer have dysphagia, hoarseness, malaise, or headache. Mild pharyngeal injection is followed by unilateral or bilateral tonsillar membrane formation, which can extend to involve the uvula (which may cause toxin-mediated paralysis), soft palate, posterior oropharynx, hypopharynx, or glottic areas (Fig. 180-1). Underlying soft tissue edema and enlarged lymph nodes can cause a bull-neck appearance. The degree of local extension correlates directly with profound prostration, bull-neck appearance, and fatality due to airway compromise or toxin-mediated complications (Fig. 180-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree