Chapter 34 Diarrhea (Case 6)

Patient Care

Clinical Thinking

• Is the dehydration significant enough to require IV fluid administration, or will the parents be able to orally rehydrate?

History

• Assess hydration status: Inquire about the number of stools, emesis, frequency and amount of urination, and overall activity level.

Physical Examination

• Vital signs: Heart rate and blood pressure. Tachycardia is common with dehydration, but hypotension is a late finding of severe hypovolemia.

• First assess appearance. Does the child appear well, sick, or critically ill? A severely dehydrated child is often lethargic and not interactive with his/her parents or the examiner.

• Check for other signs of infection, because several nonenteric infections such as otitis media, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections may cause diarrhea.

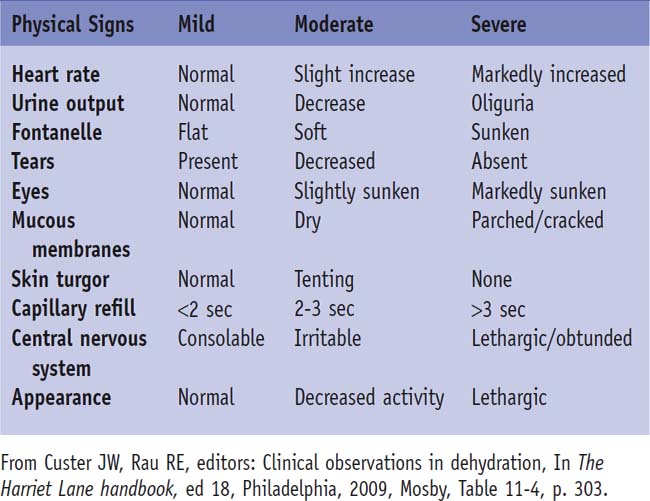

• A thorough examination assessing for signs of dehydration is important to determine the volume deficit (Table 34-1).

Tests for Consideration

• Stool studies

• Reducing substances: The presence of stool sugars may indicate malabsorption or lactase deficiency $80

Clinical Entities

| Viral Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | The virus directly invades and destroys enterocytes, resulting in the loss of the ability to absorb certain foods and loss of fluid and electrolytes into the stool. Some viruses such as rotavirus may also secrete an enterotoxin that alters enterocyte transport of calcium, leading to more water loss in the stool. Other viruses include calicivirus, astrovirus, and adenovirus. |

| TP | The typical patient has vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and occasionally abdominal pain. Stools are watery without blood, and there may be as many as 20 per day. There is often a history of exposure. |

| Dx | The diagnosis is usually clinical. A rapid test for rotavirus is available. Helpful clues to distinguish viral from bacterial disease are that viral gastroenteritis tends to occur in young children, vomiting is more likely, and generally hematochezia is absent. |

| Tx | Treatment of all infectious diarrhea is basically the same. Supportive care with fluid repletion is the mainstay. The type of fluid rehydration depends on the degree of dehydration, with severely dehydrated children requiring IV repletion. Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) with glucose- and electrolyte-containing solutions such as Pedialyte or Infalyte is considered the best option but may not be possible in children who are not tolerating fluids, are excessively vomiting, or are severely dehydrated. ORT should initially be given in frequent small volumes and advanced slowly. A child who is significantly dehydrated may benefit from initial IV fluids followed by an oral challenge to see if the child can be maintained without continued IV fluids. Early refeeding has been shown to result in faster resolution. Antidiarrheal medications such as loperamide can delay transit time and prolong the diarrhea, and should be avoided. Probiotics such as lactobacillus have been shown to reduce stool output and duration of diarrhea by altering intestinal flora. See Nelson Essentials 112. |

| Bacterial Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Several pathologic mechanisms produce bacterial diarrhea. These include enterotoxin production and direct cell invasion and destruction. This destruction leads to an impaired ability to absorb certain foods and digest complex carbohydrates, resulting in both a secretory and osmotic form of diarrhea. Some bacteria like Staphylococcus aureus and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, the cause of traveler’s diarrhea, produce cytotoxins that directly cause intestinal cell damage resulting in diarrhea. Salmonella, in particular, may cause systemic illness by invading enterocytes and subsequently entering the bloodstream, which may lead to bacteremia, osteomyelitis, or meningitis. Other bacterial pathogens include Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio cholerae, Bacillus cereus, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Clostridium difficile. |

| TP | There are diarrhea and fever, but vomiting is less common. The diarrhea may be bloody. There may be a history of travel or abdominal pain. The incubation period can range from 1 to 7 days. The presentation of Yersinia infection may mimic appendicitis. |

| Dx | A stool culture will identify the specific pathogen. Fecal leukocytes on Wright stain suggests a bacterial etiology, but they may also be present in IBD or milk protein intolerance in infants. |

| Tx | See treatment of viral gastroenteritis above. Fluid and electrolyte resuscitation is provided as needed. Antibiotics should not be routinely used in acute bloody diarrhea until the specific pathogen is identified by culture. Antibiotics are indicated for certain infections, such as Campylobacter and Shigella in all ages, for Salmonella in infants under 3 months of age, and in any age with bacteremia. See Nelson Essentials 112. |

| Protozoan and Parasitic Infections | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | These organisms invade enterocytes, leading to intestinal inflammation, villous atrophy, and malabsorption. The protozoans typically invade intestinal cells in the trophozoite stage. Examples include Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Isospora belli. |

| TP | Symptoms may vary depending on the organism. There may be gradual onset of colicky abdominal pain with flatulence and frequent stools and profuse diarrhea containing blood or mucus. Foul-smelling diarrhea, abdominal distention, gastroesophageal reflux, and frequent loose stools accompany Giardia infections. The diarrhea is often chronic, lasting more than 14 days. Travel to an endemic area such as a tropical country is a risk factor. Cryptosporidium should be considered in immunocompromised patients and those in day care. |

| Dx | Stool for ova and parasites should be sent for 3 consecutive days. Giardia can also be identified in a specific stool antigen test. |

| Tx | Supportive care with fluid repletion is the cornerstone of treatment. Many protozoan and parasitic infections are also treated with metronidazole. See Nelson Essentials 112. |

| Pseudomembranous Colitis | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Antibiotic-associated diarrhea is due to the overgrowth of toxin-producing Clostridium organisms in the bowel. Antibiotics are the culprit because they often disrupt the normal intestinal flora, leading to this bacterial overgrowth. C. difficile organisms then release enterotoxins that lead to mucosal injury and inflammation, resulting in formation of a shallow ulcer on the mucosal surface, which characterizes the colonic pseudomembrane. It can also be transmitted as a primary pathogen. |

| TP | There are acute watery diarrhea with lower abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis. |

| Dx | Identification of the C. difficile cytotoxins A and/or B is diagnostic. |

| Tx | Fluid repletion is administered as needed. Metronidazole is the primary treatment. The inciting antibiotics should be stopped. Severe infection or bowel perforation may require surgery. Probiotics can help replete normal intestinal flora. See Nelson Essentials 112. |

| Malabsorption | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | Malabsorption typically occurs as an osmotic diarrhea in which an added absorbable solute is not absorbed properly. This solute draws water into the gut lumen by altering its concentration gradient. This additional solute results from the inability to break down certain complex carbohydrates such as lactose, which can occur because of a lactase deficiency or from a lack of pancreatic enzymes as in cystic fibrosis. Celiac disease also results in malabsorption secondary to villous atrophy resulting from gliadin intolerance. |

| TP | There is usually chronic watery diarrhea. Other systemic findings include failure to thrive, frequent respiratory infections, or anemia suggesting the overall disorder. Lactase deficiency is a transient problem in younger children, often secondary to an episode of gastroenteritis in which mucosal injury leads to the deficiency. Older children may develop a primary lactase deficiency. A child with cystic fibrosis may present with failure to thrive and a history of frequent respiratory infections. Celiac disease can present as chronic diarrhea and anemia, or more commonly is asymptomatic. |

| Dx | Tests for stool-reducing substances will detect complex carbohydrates in the stool. In addition, specific tests for cystic fibrosis, celiac disease, or lactase deficiency can be pursued based on clinical suspicion. |

| Tx | Treatment of the underlying disorder will correct the diarrhea. In cystic fibrosis specific pancreatic enzymes are taken with each meal. Celiac disease is treated by avoidance of gluten, and lactase deficiency by avoidance of lactase-containing products. See Nelson Essentials 126, 129, and 137. |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | |

|---|---|

| Pϕ | The exact mechanism of IBD is unknown, but the common final pathway is inflammation. Inflammation leads to ulceration, edema, and bleeding. Ulcerative colitis involves the colonic superficial mucosa and always involves the rectum with a variable degree of proximal involvement. Crohn’s disease is a transmural disease, affecting anywhere from the mouth to the anus, and is characterized by skip lesions and noncaseating granulomas. |

| TP | The first episode may present as acute bloody diarrhea. There is often a history of weight loss, poor growth, recurrent abdominal pain, aphthous ulcers, arthritis, and anal skin tags. In addition, a prolonged duration of bloody diarrhea suggests IBD. In rare cases, a child will present with growth failure without gastrointestinal symptoms. |

| Dx | Either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease should be suspected based on clinical signs such as growth failure, anemia, abdominal pain, or bloody diarrhea. Laboratory testing may show increased white blood cells, platelets, sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein in addition to decreased albumin. There may be fecal leukocytes. Precise diagnosis is confirmed by colonoscopy and endoscopy with biopsy and visualization of characteristic features. |

| Tx | Treatment involves management of flares in addition to preventive therapy that is specific to the disease. Most treatment involves immunomodulators such as corticosteroids, aminosalicylates, methotrexate, and infliximab. Any concurrent infection is also treated, usually with metronidazole. See Nelson Essentials 129. |

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree