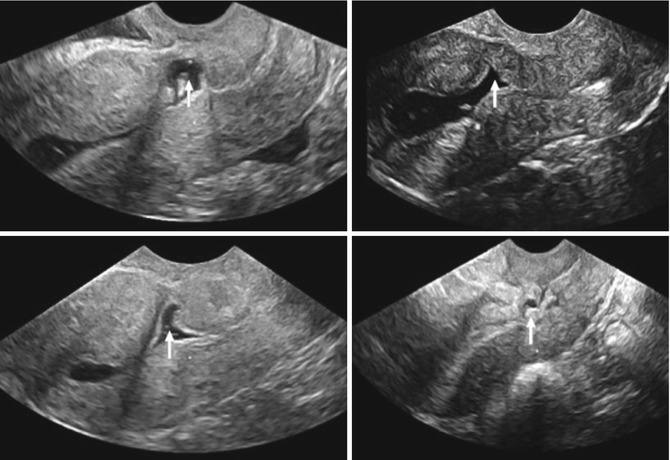

Fig. 7.1

Schematic diagram of a caesarean scar defect, also known as a niche

However, more shapes have been described (Figs. 7.2 and 7.3). A generally accepted definition for a niche is still under debate. Alternative terms for a niche are caesarean scar defect (Armstrong et al. 2003; Vikhareva Osser et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2009), deficient caesarean scar (Ofili-Yebovi et al. 2008), diverticulum (Surapaneni and Silberzweig 2008), pouch (Fabres et al. 2003), and isthmocele (Borges et al. 2010). Some of these terms are unfortunate as they imply a relationship between the appearance of the niche and function, particularly in any future pregnancy. Until now there is no evidence yet to underline a relation with the appearance of the CS and its function. In this chapter, we will use the term “niche.”

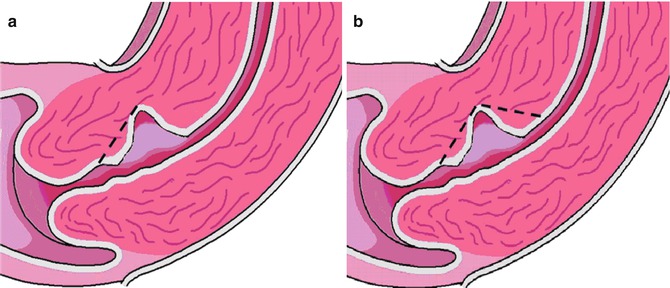

Fig. 7.3

Niche shape. Schematic diagram demonstrating classification used to assess niche shape: triangle, semicircle, rectangle, circle, droplet and inclusion cysts (Published in Bij de Vaate et al. 2011)

7.2 Prevalence of Niches and Diagnostic Methods

Various methods to detect and measure a niche have been described. In earlier publications, it was observed during hystesterosalpingraphy (Surapaneni and Silberzweig 2008). However, this method may be considered as less imprecise for this objective and small niches may be missed. The most applied techniques are transvaginal sonography (TVS) (BijdeVaate et al. 2011; Vikhareva Osser et al. 2009; Armstrong et al. 2003) and sonohysterography (SHG) (BijdeVaate et al. 2011; Vikhareva Osser et al. 2009; Regnard et al. 2004; Valenzano et al. 2006). The latter technique is proposed to be more accurate due to improved delineation of the borders of a niche in comparison with TVS (Vikhareva Osser 2010a). This is underlined by a larger proportion of patients with a niche after SHG in comparison to TVS. BijdeVaate et al. (2011) observed in 56 % of women a niche using SHG compared to 24 % using TVS 6–12 months after a CS in a prospective cohort study. This is in line with an other prospective cohort study, studying niches in women after a CS, reporting a niche in 84 % of women using SHG compared to 70 % using TVS (Vikhareva Osser 2010a). Using SHG, the prevalence of niches in relatively unselected women after CS varies between 56 and 84 % (BijdeVaate et al. 2011; Regnard et al. 2004; Valenzano 2006; Vikhareva Osser 2010a). Reported prevalence of niches in women after CS using hysteroscopy varies between 31 and 88 % (Borges et al. 2010; El-Mazny et al. 2011). Besides the applied diagnostic methods, the prevalence of niches is highly dependent on the population, the awareness of the observers and of course the applied definitions. Until now there is no agreement about the gold standard for the detection and measurement of a niche. Higher prevalence is expected in women undergoing examination because of symptoms such as bleeding disorders or fertility problems. CS scar assessment during pregnancy is a different topic and requires other techniques and definitions since a SHG is not possible to apply. Naji et al. studied CS scars during pregnancy using TVS and was able to detect CS scars with low inter- and intra-observer variability (Naji et al. 2012b).

7.3 Niche Shapes

Various niche shapes have been described using sonography (see Figs. 7.2 and 7.3). Most studies report on a triangular shape (Vikhareva Osser et al. 2009; Chen et al. 1990). Using sonohysterography, the semicircular and triangular shapes were reported to be most prominent (BijdeVaate et al. 2011). Another reported classification based on the direction of the external surface is inward protrusion (internal surface bulging toward the bladder), outward protrusion (external surface bulging toward the bladder) or inward retraction (external surface of the scar dimpling toward the myometrial layer). (Chen et al. 1990).

7.4 Predisposing Factors for Niches

As not all women with a history of CS develop a niche, it is a subject of interest to identify the risk factors for the development of a niche. Several publications tried to elucidate the main risk factors, however, most individual publications are of insufficient power to study all relevant risk factors. Different diagnostic methods were used to identify niches in a selected population of women with gynaecological symtoms and used definitions were not uniform and often not clearly defined. So far only two studies have studied risk factors in an unselected population after a CS (Armstrong et al. 2003; Vikhareva Osser 2010a). Three other studies were performed in a population of women who were assessed for a variety of gynecological symptoms (Monteagudo 2001; Wang et al. 2009; Ofili-Yebovi et al. 2008).

Cervical dilatation and station of the presenting fetal part below pelvic inlet at the time of CS were the only predictive factors in one prospective study including patients with only one previous CS using TVS or SHG (Vikhareva Osser 2010, 2). Prolonged labor and multiple caesarean sections were identified as risk factors for niches in an unselected population using TVS (Armstrong et al. 2003). Using TVS, multiple caesarean sections were also identified as predisposing factor for niches (Ofili-Yebovi et al. 2008) and for larger niches (Wang et al. 2009). Uterine retroflexion was also associated with niches Moeten er geen referenties bij aangezien er staat ‘several’? (Vikhareva Osser et al. 2009) However, it is not clear if the retroflected position is a predisposing factor for the development of a niche or that retroflexion is caused by insufficient CS scar healing. Suturing technique should be considered as a predisposing factor as well. There are two small randomized trials and one prospective trial studying the effect of the suturing technique on the prevalence of a niche using ultrasound 4–6 weeks after the CS (Hayakawa et al. 2006; Hamar et al. 2007; Yazicioglu et al. 2006). There was no difference in myometrial thickness between one-layer or two-layer closure (Hamar et al. 2007), but there were less niches identified after double-layer closure compared to single layer (Hayakawa et al. 2006) or to split-level closure without inclusion of the endometrial layer (Yazicioglu et al. 2006).

7.5 Related Symptoms

Several complications of a scar defect have been reported, including niche pregnancies (BijdeVaate et al. 2010), malplacentation (Naji et al. 2013a), and perforated intrauterine devices (Voet et al. 2009). Recently, it has been shown that the thickness of the residual myometrium is an independent prognostic factor for success rate after trial of labor (Naji et al. 2013). However, the exact risk of niches on uterine ruptures has to be elucidated.

The relation between a niche and gynecological symptoms in non-pregnant patients has been acknowledged only recently. An association between a niche and prolonged menstrual bleeding and postmenstrual spotting has been reported in several studies (BijdeVaate et al. 2011; Fabres et al. 2003; Regnard et al. 2004; Thurmond et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2009; Borges et al. 2010). A niche is observed in almost 60 % of all women after a CS. The incidence of postmenstrual spotting is higher in these patients compared to those without a niche (OR 3.1 [95 % CI, 1.5–6.3]) (BijdeVaate et al. 2011). An association between the size of the niche and postmenstrual spotting is reported in three studies (Wang et al. 2009; Bij de Vaate et al. 2011; Uppal et al. 2011). Whilst a larger niche volume was demonstrated in women with postmenstrual spotting, there was no relation with the shape of the niche (BijdeVaate et al. 2011). In another study (Wang et al. 2009), scar defects were significantly wider in women with postmenstrual spotting, dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain. In the third study, the incidence of postmenstrual spotting or prolonged menstrual bleeding was higher with an increase of the diameter of the niche (Uppal et al. 2011). Niche-related menstrual bleeding disorders do often not respond to hormonal therapies and are associated with cyclic pain (Gubbini et al. 2008) and may be responsible for a substantial part of gynecological consultations and interventions. Other reported symptoms in women with a niche were dysmenorrhea (53.1 %), chronic pelvic pain (36.9 %), and dyspareunia (18.3 %) (Wang et al. 2009).

7.6 Etiology of Niche-Related Bleeding Disorders

It has been assumed that abnormal uterine bleeding may be due to the retention of menstrual blood in the niche, which is intermittently expelled after the majority of the menstruation has ceased, causing postmenstrual spotting and pain (Thurmond et al. 1999; Fabres et al. 2005). The presence of fibrotic tissue below the niche may impair the drainage of menstrual flow (Fabres et al. 2003). Additional new formed fragile vessels in the niche may also attribute to the accumulation of in situ produced blood (Morris 1995).

7.7 Treatment Modalities

Since the recent acknowledged association between CS-related niches and bleeding disorders, several innovative surgical therapies have been developed. The effectiveness of surgical interventions for the treatment of niche-related uterine bleeding disorders has been reported in a limited number of studies. Most studies include case reports or small prospective or retrospective case series. Surgical treatment includes hysteroscopic resection (Chang et al. 2009; Fabres et al. 2005; Gubbini et al. 2008, 2011; Wang et al. 2011), laparoscopic (Donnez et al. 2008; Klemm et al. 2005) or vaginal repair (Klemm et al. 2005).

7.8 Hysteroscopic Niche Resection

The least invasive surgical therapy, which can be performed in day care, is the hysteroscopic resection of the niche. The proposed theory behind this treatment is to improve outflow of menstrual blood and to prevent in situ produced hemorrhage by the fragile vessels in the niche itself.

7.8.1 Technique

The hysteroscopic resection was all done by a monopolar resectoscoop varying between 9 and 12 mm. In most studies, the distal part of the niche was resected with (Fabres et al. 2005; Chang et al. 2009) or without coagulation of the bottom of the niche (Fernandez et al. 1996) (see Fig. 7.4). In some studies both the distal and the proximal part of the niche were resected (see Fig. 7.4b) in combination with coagulation of the bottom with a rollerball (see Figs. 7.4b and 7.5) (Wang et al. 2009; Gubbini et al. 2008, 2011). Given the potential risk on perforation or bladder injury a certain distance between the niche and bladder is required, also known as residual myometrium, presented as 2 in Fig. 7.6. Minimal required residual myometrium thickness varies among the different studies between 2 and 2.5 mm (Wang et al. 2009; Gubbini et al. 2008, 2011).