Introduction

Suspected fetal macrosomia is encountered commonly in the practice of obstetrics. The delivery of large fetuses remains clinically important because of the increased potential for maternal and neonatal complications. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics shows that 10% of liveborn infants in the Unites States weigh more than 4000 gm at birth, and about 1.5% weigh more than 4500 gm. Potential maternal risks of macrosomia include abnormal labor, uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage, lacerations, and infection. Potential risks to the fetus include shoulder dystocia (see also Chapter 12, “Shoulder Dystocia”), brachial plexus injury, bone fractures, and in rare cases asphyxial injury. Some studies have also suggested that fetal macrosomia can lead to childhood obesity, glucose intolerance, and development of metabolic syndrome.

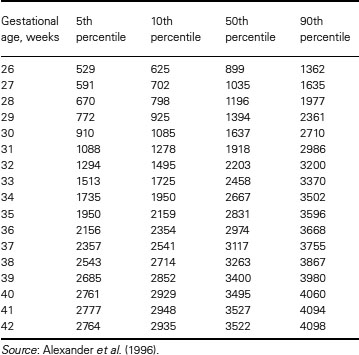

The terms macrosomia and large for gestational age (LGA) both refer to excessive fetal growth. Even though there is no universal agreement regarding the absolute threshold for macrosomia, historically it has been defined as a birth weight exceeding 4000 gm independent of gestational age. The term “large for gestational age” refers to infants whose birth weight exceeds the 90th percentile for growth at a specific gestational age. Birth weight data from the National Center for Health Statistics is listed in Table 8.1. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists acknowledges that there is increased morbidity in infants with a birth weight > 4000 gm, but they recommend that macrosomia be defined as any infant with an estimated fetal weight above 4500 gm. This recommendation is most likely based on data regarding birth injury and the difficulty in assessing fetal weight accurately prior to delivery. It should also be noted that male infants, on average, have higher birth weights than female infants, and that racial and ethnic differences can also influence birth weight.

Table 8.1 Percentiles of birth weight (grams) by gestational age: U.S. singleton births, 1991

There are several historic risk factors described in association with macrosomia. These include: maternal diabetes, multiparity, male fetus, advanced maternal age, maternal obesity (or high body mass index), prior history of macrosomia, postterm pregnancy, maternal birth weight over 4000 gm, Hispanic or African-American ethnicity, and excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Approximately one-third of all neonates over 4000 gm at birth are born to diabetic mothers. Even though the risk of accelerated fetal growth in infants of diabetic mothers increases with increasing hyperglycemia, there is no universal threshold value of hyperglycemia that predisposes the fetus to becoming macrosomic. Conversely, in diabetic women with good glycemic control, the rate of macrosomia approaches that of the general population (10–13%). There are also rare causes of genetic macrosomia, such as in fetuses with Beckwith-Wiedemann or Weaver syndromes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree