Introduction

Gestational diabetes refers to any degree of glucose intolerance with variable severity with the onset or first recognition during pregnancy. This complicates approximately 4–7% of pregnancies. The prevalence may range from 1% to 14%. About 90% of diabetes in pregnancy is gestational diabetes. This does not exclude the possibility of unrecognized pre-existing diabetes before pregnancy. Pregestational diabetes, which accounts for 5–10% of diabetes in pregnancy, refers to diabetes diagnosed before pregnancy. Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder that can significantly alter the maternal and in utero environment, leading to complications. Optimizing maternal glucose is central to the management of diabetes in pregnancy because it has been shown that most complications in pregnancy can be prevented or controlled.

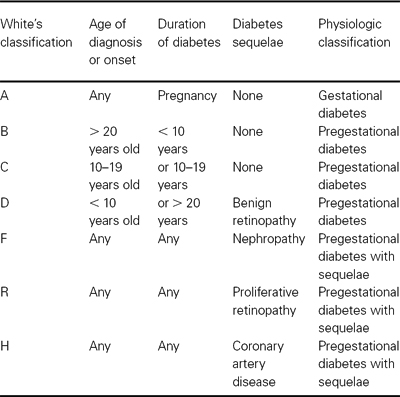

The most widely used classification of diabetes mellitus in pregnancy is the White classification. The categorization was used to indicate the duration of disease, age of onset in relation to the pregnancy, and the presence or absence of diabetic complications (Table 30.1). This classification has become less useful as the pathogenesis of diabetes and the effects of complications on the outcome of pregnancy are better understood. From a clinical management perspective, it is more useful to group patients into three functional groups.

- Gestational diabetes (patients developing diabetes for the first time during pregnancy)

- Preconceptional diabetes without diabetic sequelae (both insulin-dependent and noninsulin-dependent diabetes)

- Preconceptional diabetes with significant diabetic sequelae (nephropathy, advanced retinopathy, autonomic neuropathy or coronary artery disease)

Table 30.1 Classification of diabetes during pregnancy

Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

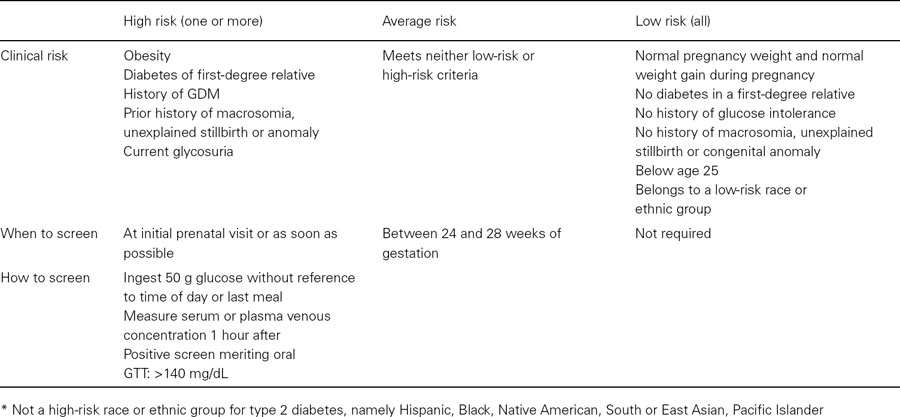

Recommendations for screening for gestational diabetes mellitus are not universally agreed upon. The Fourth International Workshop Conference on Gestational Diabetes recommends screening for gestational diabetes based on an initial assessment of individual risk in all pregnant women (Tables 30.2, 30.3). High-risk criteria include those 25 years or older, belonging to an ethnic group with a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, diabetes in a first-degree relative, history of glucose intolerance or prior gestational diabetes, prior history of macrosomia, unexplained stillbirth or congenital anomaly, current glycosuria. Women with high-risk factors should undergo screening at the first visit or as soon as possible, while individuals who continue to exhibit low-risk characteristics do not require screening. A 1-hour 50 g glucose challenge test performed randomly without regard to time or eating is recommended. If the initial screen is < 140 mg/dL in high-risk individuals, the screening test should be repeated or performed at 24–28 weeks’ gestation. Routine screening is not required if the individual meets all low-risk criteria. Routine screening at 24–28 weeks is recommended for those not meeting low- or high-risk criteria.

Table 30.2 Clinical screening for gestational diabetes based on clinical characteristics

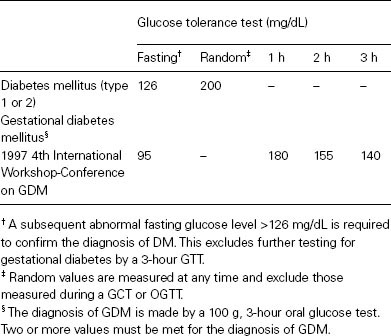

Table 30.3 Diagnosis of diabetes during pregnancy based on the recommendations of the Fourth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

The US Preventive Services Task Force states that there is insufficient evidence to assess the balance between the benefits and harm of screening for GDM either before or after 24 weeks’ gestation and clinicians should discuss screening with their patients on a case-by-case basis. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends universal screening since there is a high prevalence of pregnant patients meeting the high-risk criteria. The Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS), a multicenter control trial of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) versus routine prenatal care found a reduction in the composite of severe perinatal outcomes in the treatment group. The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study, a multiinstitutional study, found strong associations between higher level of maternal glucose at 24–32 weeks, within normoglycemic levels, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Given that hyperglycemia and pregnancy complications are strongly associated and that managing gestational diabetes reduces complications, the results support screening for GDM. Current recommendations for screening in pregnancy are being debated internationally. LAC/USC Medical Center screens every pregnant woman at the first visit and if negative, again at 24–28 weeks. This is based on the high prevalence of risk criteria in our population.

A glucose challenge test (GCT) is recommended for screening for GDM. Fifty grams of oral glucose is ingested without diet preparation, at any time of day, with a venous plasma glucose level measured 1 hour later. A positive screen is defined as greater than or equal to 140 mg/dL. Some recommend 130 mg/dL and require a follow-up oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to diagnose GDM. Using a cut-off of 130 mg/dL increases the sensitivity by 10% but results in almost twice as many OGTT performed. If the GCT equals or exceeds 200 mg/dL, the risk of undiagnosed diabetes is increased. We recommend measuring overnight fasting plasma glucose the next day. If the fasting plasma glucose is equal to or greater than 126 mg/dL, no further testing is necessary; the patient has undiagnosed diabetes. Otherwise an OGTT is performed after an overnight fast of 8–14 hours after 3 days of unrestricted carbohydrate intake. Venous plasma glucose levels are measured fasting and at 1, 2, and 3 hours. The diagnosis of GDM is made when two or more values meet or exceed the cut-off thresholds based on the Fourth International Conference Workshop Conference on GDM: fasting, 95 mg/dL; 1 hour, 180 mg/dL; 2 hour, 155 mg/dL; 3 hour, 140 mg/dL. Diagnosis is a vital step in the management of GDM. Once the diagnosis is made, achieving euglycemia leads to reduction of perinatal complications.

Pregestational diabetes mellitus

Women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus may have insulin-dependent (IDDM or type 1), noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM or type 2) or maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY). In type I diabetes, the insulin deficiency usually results from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic β cells, leading to severe or complete insulin deficiency. In type 2 diabetes, the insulin deficiency occurs due to progressive β cell dysfunction. It is recognized that both type I and type II diabetes may be heterogeneous in etiology. MODY, an autosomal dominant form of diabetes resulting from several gene-specific mutations, provides a third category of β cell dysfunction. Although the White’s classification is still used for diagnosis, it is clinically more useful to categorize patients with pregestational diabetes into those with and without significant medical complications.

Pregnancy for the woman with diabetic sequelae significantly elevates the risk for maternal, fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and requires close and highly specialized medical care. These complications include preproliferative or proliferative retinopathy, nephropathy, autonomic neuropathy, and coronary artery disease. Many patients have multiple complications and pregnancy outcome is worse with multiple organ involvement. Women with pre-existing diabetes should undergo a baseline assessment of renal function, thyroid assessment, lipid screen. If pre-existing diabetes is greater than five years, an EKG and ophthalmology exam is also recommended.

Effects of diabetes on fetal development

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree