2.2 Developmental surveillance and assessment

Introduction

Parents know their own children best

• Always take any parental concerns or history of regression in skills very seriously (worried parents are usually right!).

• Surveillance and screening take place to ensure there are no warning signs of potential problems – if in doubt refer for therapy/intervention and then review.

• False reassurance must be avoided. Do not reassure unless you are certain of normality.

• All developmental diagnosis is dimensional across different areas of development and behaviour. It’s not black and white, but which shades of which colours blend to make up the rainbow.

• Discussion of diagnosis/prognosis requires time, privacy, empathy, honesty, cultural sensitivity and both parents whenever possible. Details of what is said may be forgotten, so written reports are essential.

• Each assessment must produce a practical written action plan that is given to the family and others involved. Otherwise, it is at risk of being ineffective.

about their child’s progress, such as ‘Tell me how she is getting around’, as they are more likely to elicit revealing answers than ‘Is she walking now?’. This process is time-consuming and parents need to feel relaxed and unhurried if they are to give their best information. Some of the information may well be sensitive, especially when there are problems, and a private setting without interruptions is important. Developmental interactions are best scheduled for a well-child visit or review to avoid confusing illness behaviour with developmental delay.

History is everything

A good developmental history starts with the pregnancy and delivery, and progresses through the neonatal, infancy, toddler and preschool years; it should be a routine part of all paediatric interactions. The doctor requires a working knowledge of normal development and needs to be aware of the significance of variations that may indicate a developmental disorder. Child development progresses in many areas simultaneously (Table 2.2.1). It is as necessary to know the various developmental systems as it is to know the physical systems. Each will have its component parts, and the rate of progress in all of these components may be similar (when all are delayed, this is described as global delay) or discrepant (described as a specific delay in one area).

Table 2.2.1 Areas of development

| Area | Description |

|---|---|

| Gross motor | Large muscle movements – walking, running, jumping, climbing and riding |

| Fine motor | Small muscle movements – grasp, release, drawing, speech clarity |

| Language | Receptive – understanding others |

| Expressive – own thoughts output | |

| Pragmatic – social use, conversation | |

| Social and daily living skills | Adult and child interaction |

| Feeding, dressing, washing, toileting |

Checking the normal (surveillance)

What are the normal ranges?

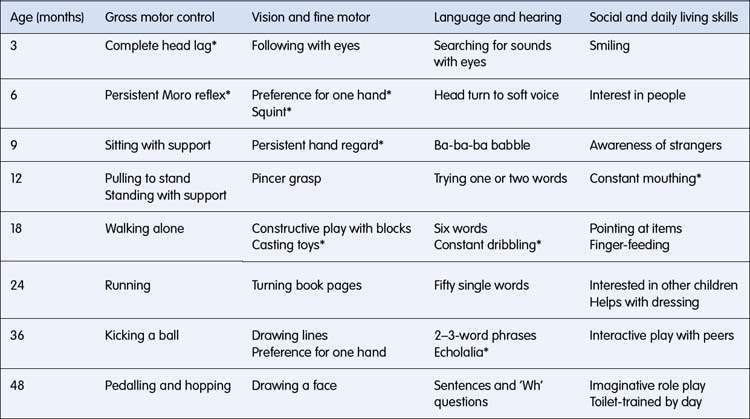

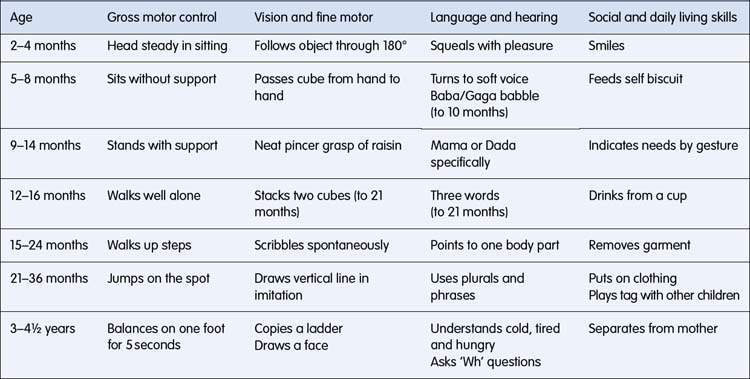

The key is to look for areas of development delayed beyond the normal range and not to compare the child with ‘normal milestones’, which are merely the average age of achievement. By definition, half of the population will not meet median milestones, and their use can worry parents unnecessarily (‘milestones are millstones’). It is preferable to use the normal ranges in Table 2.2.2. Many developmental patterns are familial, but so are many developmental disorders, so it is unwise to accept delay as a normal variation. Just because an uncle did not talk until he was 4 years old does not mean he did not also have a developmental language disorder or deafness. Other ‘causes’ such as being a twin, bilingualism or tongue-tie can produce minor variations, but not significant delays needing more formal diagnostic assessment. Assuming that the child’s delay is caused by these minor variations is a common source of late diagnosis and delayed effective intervention. The most important conclusion that needs to be drawn from this surveillance is that there are no warning signs of a potential problem (Table 2.2.3). Should doubt exist, it is always better to seek a second opinion and to arrange some therapy or intervention than to provide false reassurance. It may make you feel better to reassure, but families who waste months finding help for their child will often feel let down.

Table 2.2.2 Normal ranges for children’s developmental progress (approximately 25th to 90th percentile)

Any interaction is an opportunity to examine

As each area is reviewed through the different stages of childhood, any apparent delays or unusual features can be clarified with the family. This allows the developmental examination to be targeted. Although many children are shy and perhaps fearful, a quiet and patient approach will often bring out the show-off in children, especially for tasks about which they are confident. For this reason it is best to start looking at non-verbal areas (blocks, puzzles, drawing, etc.) and having appropriate furniture at the child’s height will enable you to get down to the child’s eye level. Simple equipment (Table 2.2.4) can be used to elicit a range of skills and the session should remain a play activity. Remember that too much direct eye contact, especially from above, can be threatening, and a relaxed tangential approach across the child may be more successful. Refusal to cooperate is a regular occurrence and it is better to reschedule than to persist and teach the child the sessions are going to be unpleasant.

Table 2.2.4 Developmental equipment

| Area | Equipment | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Gross motor | Steps | Crawling and walking up and down |

| Tennis ball | Throwing, kicking and catching | |

| Tricycle | Riding and pedalling | |

| Fine motor | Raisins | Pincer grasp and feeding |

| Small blocks | Building, colour matching and counting | |

| Inset puzzles | Matching and sorting shapes | |

| Crayon | Scribbling, drawing lines and shapes | |

| Paper (with child scissors) | For above plus cutting and folding | |

| Language | Doll | Identifying and naming body parts |

| Simple picture book | Pointing to items and describing the action | |

| Toy telephone or dictaphone | Encouraging speech samples | |

| Social and daily living skills | Mirror | Watching baby’s response to self |

| Toy cup, plate and cutlery | Feeding the doll and pretend tea party |

The aim of the medical examination (see Chapter 2.1) is to detect any condition that might be causing the developmental delay, or indeed any general medical problem that may be exacerbating it. You should note the child’s growth parameters, especially head circumference, and any signs of dysmorphism or neurocutaneous disorders. Although a thorough physical examination is desirable, particular attention needs to be paid to the neurological system, looking for signs of cerebral palsy and other neuromotor disorders (see Chapter 17.2). Some ingenuity may be needed after a long developmental session to re-engage the child in play.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree