6 Developmental Management of Toddlers and Preschoolers

Development of Toddlers and Preschoolers

Development of Toddlers and Preschoolers

Physical Development

Physical and physiologic changes in toddlers and preschoolers continue at a much slower pace than in the first year of life. Statistically, children gain weight faster and earlier than children in earlier decades (Trifiletti et al, 2006); however, growth charts continue to show the average 2-year-old weighs 26 to 28 pounds (12.5 to 13.5 kg), with boys being slightly heavier than girls, and is 34 to 35 inches (85 to 90 cm) tall. Head circumference in the average 2-year-old is 19 to 19.5 inches (48 to 50 cm). Although most toddlers have no palpable fontanelles by 12 months, the anterior fontanelle should completely close by 18 to 19 months. During the fourth and fifth years, skeletal growth continues as additional ossification centers appear in the wrist and ankle and additional epiphyses develop in some of the long bones. For the 4- to 5-year-old, the legs grow faster than the head, trunk, or upper extremities. Changes related to body systems are highlighted in Table 6-1. More detailed discussion of development, systems, and disease processes can be found in Units 3 and 4 of this text.

TABLE 6-1 Physical Development of Toddlers and Preschool-Age Children

| Body System | Developmental Changes |

|---|---|

| Dental | By 12 mo, the child usually has 6 to 8 primary teeth. |

| By 2 yr, the child has a complete set of 20 primary teeth. | |

| By 3 yr, the second molars usually erupt. | |

| During the second year, calcification begins for the first and second permanent bicuspids and second molars. | |

| Most growth and calcification of the permanent teeth occur within the gums; it is not visible. | |

| Neurologic | Continued myelinization and cortical development occurs. |

| Fine motor movements are more detailed and sustained: | |

| Gross motor skills are smoother and more coordinated. | |

| Sensory function is more mature. | |

| Visual acuity is 20/70 for 2-year-olds; 20/30 for 5- to 6-year-olds. | |

| Cardiovascular | Little change occurs in the second and third year. |

| By the fifth year, the heart has quadrupled in size since birth. | |

| By 5 years, the heart rate is typically 70 to 110 bpm. | |

| Normal sinus arrhythmia may continue, and innocent murmurs are common. | |

| The hematologic system should produce only adult hemoglobin by the fifth year. | |

| The hemoglobin level stabilizes at 12 to 15 g/dL. | |

| Pulmonary | Abdominal respiratory movements continue until the end of the fifth or sixth year. |

| Respiratory rate slows to about 30 breaths per minute. | |

| Gastrointestinal | By 2 years, the salivary glands reach adult size. |

| The stomach becomes more bowed and increases its capacity to about 500 mL. Many children still require a nutritious snack between meals because of small stomach size. | |

| During the second year, the liver matures and becomes more efficient in vitamin storage, glycogenesis, amino acid changes, and ketone body formation. The lower edge of the liver may still be palpable. | |

| By 4 to 5 years, the gastrointestinal system is mature enough for the child to eat a full range of foods. | |

| Stools are more like those of adults. | |

| Renal | Kidneys begin descending deeper into the pelvic area and grow in size. |

| Ureters remain short and relatively straight. | |

| A 2-year-old may excrete as much as 500 to 600 mL of urine a day. | |

| A 4- to 5-year-old excretes between 600 and 750 mL daily. | |

| Endocrine | Quiescent time for sexual growth, with few physical or hormonal changes. |

| Growth hormone stimulates body growth. |

bpm, Beats per minute.

Motor Development

Motor development is divided into two components—gross and fine. Gross motor refers to the development and use of the large muscles. Fine motor includes hand and finger development and oral-motor development (see Table 5-1 for a review of gross and fine motor milestones by age).

Communication and Language Development

• Oral-motor ability to articulate sounds

• Auditory perception to distinguish words and sentences

• Cognitive ability to understand syntax, semantics, and pragmatics

• Psychosocial-cultural environment to motivate the child to engage in language use

Language milestones are evident in two general categories—receptive and expressive language. These are presented for infants and children younger than 5 years old in Table 5-2.

Articulation

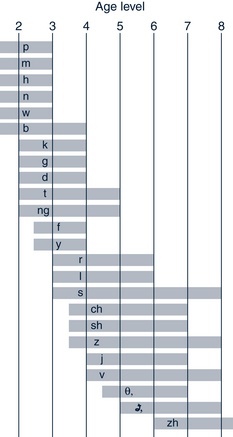

Young children practice articulation skills daily, and by 24 months speech sounds are 25% intelligible to a stranger. The intelligibility rate jumps to about 66% between 24 and 36 months, with 90% intelligibility by 3 years old. By 4 years, speech should be completely intelligible with the exception of particularly difficult consonants. By 5 years the tongue-contact sounds of “n,” “t,” “d,” “k,” “g,” “y,” and “ng” are more intelligible. Some sounds, such as the “zh” sound, are not added until the child is 6 to 8 years old. Figure 6-1 identifies sounds articulated by children at specific ages.

FIGURE 6-1 Norms for development of speech sounds. θ, th as in thin;  as in this.

as in this.

(From Van Riper C, Erickson RL: Speech correction: an introduction to speech pathology and audiology, ed 9, Needham Heights, MA, 1996, Allyn & Bacon, p 98. Reprinted by permission.)

Semantics

Semantic development, the understanding that words have specific meaning and the child’s use of words to convey specific meaning, is an ongoing process extending into adulthood. This development occurs in stages from global to more specific and requires interaction through conversation, listening, and reading. Words used in any language have both denotative (the specific, concrete referent of the word) and connotative (a broader range of feelings aroused by the word) meanings. Even though children may be quite adept at using words correctly, they may have only a vague, diffuse connotative understanding of these words. For example, the 3-year-old who drops a toy and uses an expletive she heard when her father dropped a dish does not understand the connotative meaning of what she has said. As language progresses from simple to more complex, meaning and cognitive understanding evolve.

Social and Emotional Development

Preschool children are much less dependent on their parents and frequently tolerate physical separation for several hours. As this sense of separateness increases, children are more aware that they are different from their surroundings, their families, and their friends. They begin to realize that other persons also have feelings, fears, and doubts. Peer dependence and learning about how to have and be friends begin to be important.

Sibling Interaction

Interaction patterns between siblings vary and are affected by factors such as opposite gender, temperament, insecure attachment, family discord, corporal punishment, and perceptions of unequal treatment. Many toddlers or preschoolers regress when a new baby arrives, whereas older children may experience excitement, love, and enhanced self-esteem with a new sibling. Parents need to promptly limit any aggression expressed by the older child, provide love and attention, and talk about feelings. When older children fight, parents need to describe the situation and provide even-handed control. Blaming a child, except in a clear-cut instance of misbehavior, is usually unproductive. Promoting support, loyalty, and friendship is important for sibling interactions (see Chapter 17).

Body Image

Preschoolers are equally curious about their bodies but are more capable of understanding and expressing themselves. They reexamine themselves frequently, and worries over a lost tooth or a skinned knee are common. Curiosity about their bodies and those of others generates a wealth of innocent questions that generally require only a simple answer. They learn that genital manipulation brings pleasure, and masturbation peaks around 3 to 4 years.

Cognitive Development

Cognitively, toddler thinking is highly concrete. According to Piaget (see Table 4-1), 18- to 24-month-old children use mental imagery and infer causality when they can see only the effect. By the end of the second year children enter the preoperational stage with preconceptual and intuitive thinking. Primitive conceptualization processes begin with the development of symbolic thinking. A block becomes a car; words become symbols for ideas. The 3-year-old continues to develop symbolic thinking, and this manifests through drawing and acting out elaborate play scenarios. However, children at this age generally are unable to take another’s perspective but continue to view the world egocentrically. Attending to one characteristic at a time is another feature of preschool thinking. For example, the child will try to fit a jigsaw puzzle piece using either color or shape but not both.

Parents may have difficulty understanding the thoughts of preschool children. On the surface preoperational thinking has many characteristics that resemble adult thinking, and parents are often deceived into believing that children are able to think as adults do. Preschool children, for example, are developing the use of language and the ability to symbolize concepts mentally. Some of their verbalizations appear quite precocious, as evidenced by the 3-year-old who stares out the window and then states, “Look, mommy, the trees are saying yes and no.” Preschool children continue to be concrete and egocentric in their thinking, and their logic is the source of many communication problems between parents and children. Table 6-2 identifies major characteristic of preschool thinking and gives examples of each.

TABLE 6-2 Examples of Preschool Children’s Thinking Using Piaget’s Preoperational Stage

| Characteristic | Example |

|---|---|

| Egocentricism | “It’s snowing so I can go play in it.” |

| Unable see another’s viewpoint | If John is holding a doll with its face toward Ann, Ann thinks John can also see the doll’s face. |

| Mental symbolization of the environment | < div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|