7 Developmental Management of School-Age Children

School-Age Child Development

School-Age Child Development

Physical Development

The growth rate of school-age children increases significantly from that of the toddler and preschooler and occurs in “spurts.” The child literally “grows out of his or her clothes” in a matter of weeks. Children from this age group need height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) evaluation. Head circumference increases slowly, although it is not routinely measured. By middle childhood the brain is about 90% of its adult size. Full adult brain size is reached by about 12 years old. Myelination of the brain, which is necessary for information processing, is not complete until early adulthood. The cerebral cortex (responsible for intelligence) and the frontal lobe (responsible for problem-solving, judgment, and decision-making) are the last to fully develop. The increasing maturation of the brain allows children to complete increasingly complex skills and have greater control over their bodies (see Chapter 2). Organ development is complete. Most school-age children sleep about 10 hours per night (range 8 to 14 hours) without naps, particularly during the school year. Night terrors or sleepwalking may emerge (see Chapter 14).

Table 7-1 includes a description of the significant physical changes that occur in school-agers. Discussion of school-age health issues and disease processes is found in Units 3 and 4 of this text.

TABLE 7-1 Physical Development of School-Age Children

Communication and Language Development

The child’s language patterns provide insight into the neurologic system’s status because the maturing brain is capable of increasingly complex language skills. Both receptive and expressive language skills improve. Six-year-olds have a well-developed vocabulary and retrieve words quickly. They have simple syntactic abilities and follow more complex directions than preschoolers. The language demands of school can be challenging for 6-year-olds. First, they may not be accustomed to attending to total auditory stimuli as in the classroom environment. Second, they are still mastering connotative and semantic skills such as understanding the concepts “before” and “after,” relative clauses (e.g., “the cat was chased by the dog”), and the structures of sentences. These factors can make it difficult for some to follow complicated directions or to cope with the increased demand to recall information within a specific time frame. Narrative skills can be poor, and reading may be difficult. The expressive language of 6-year-olds should be fully intelligible. Stuttering usually resolves by school age but may be seen if young children are overly eager to express themselves. Stuttering should be ignored at this age as long as it does not involve repetition of syllables or cause distress for the child.

Social and Emotional Development

The psychosocial development of school-age children puts to rest the notion that childhood is a “quiescent” period. Challenges that school-age children face are especially difficult because the child’s skill and ultimate success are dependent on abilities that are only just evolving. Gaining social acceptance from one’s peers, for example, depends on skills such as being socially responsive, understanding the group “rules,” using the group jargon, being appropriately assertive, and being empathic. Children who do not yet have those skills can experience a sense of failure when they are compared with their peers who do. Erikson stated that school-age children are eager to learn and internally motivated to achieve mastery and recognition (see Chapter 4). They need to be given experiences in an environment that recognizes, adjusts for, and supports their maturing set of skills, where they can explore creatively, learn actively, and be recognized for their successes.

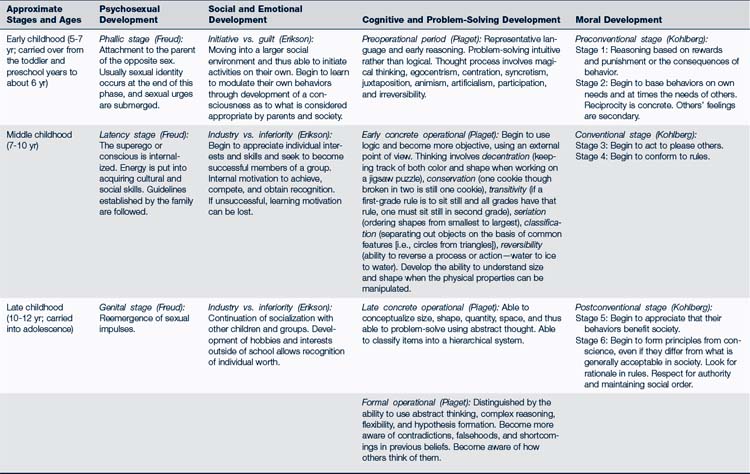

The stages through which children progress as they become more socially and emotionally mature are sequential and build on earlier skills (Table 7-2) (see Table 4-1 and discussion in Chapter 4 of the theoretical models of development). In particular, school-age children must develop social interactional skills including how to:

• Understand meaning in social situations and interpret the social cues of others

• Terminate interactions positively

• Gain impulse control and manage emotions

Mastering these skills enables children to:

• Refine their role within the family system

• Develop and maintain peer friendships

• Develop positive relationships with adults outside the family

Peer Relationships

A major task of school-age children is to develop competence in social relationships. Friendships are an important part of the school-ager’s life. They allow children to practice learned social skills, provide emotional support, and help children identify a healthy self-image. Social acceptance is especially important at this age. Friends are generally chosen because of shared skills, interests, personality, and loyalty. Children come to see themselves in the eyes of their friends. As early as 7 years old, some children are more concerned about a friend’s opinion than about adults’ opinions. They develop “best friends” and dress and talk like their peers. A special-friend phase should occur at around 10 years old. This is an intense attachment to a same-sex child. With that friend, the child expands the self, learns altruism, shares feelings, and learns how others manage problems. Talking on the telephone and sleepovers become more common. These early friendships are the basis for later relationships. Family conflicts can arise when peer activities and expectations conflict with family rules and values.

Morality

Although there is variability in moral development, moral reasoning in early childhood is usually determined by the consequences of behavior: to avoid punishment, receive rewards, or meet one’s needs. There is some consideration of the feelings of others, but only as it serves one’s needs. By 7 years old, most children name a site for their conscience (heart or brain), and, consistent with concrete thinking, school-age children tend to be rather rigid in their views of right and wrong. They can understand the relationships between responsibility and privileges and realize that choices between right and wrong behaviors are within their control. Some children at this age act appropriately to get a direct reward, whereas others view moral behavior as following the rules of higher authority (see Table 20-2). In late childhood children begin to move into Kohlberg’s postconventional stage (Kohlberg, 1981), where respect for authority and social norms develops.

Body Image

Physical growth and neurologic maturation give children the ability to master many new physical skills. Young swimmers, runners, skateboard enthusiasts, soccer players, musicians, and artists all emerge at this time. Their achievements—and failures—help them define who they are and are the basis for their evolving self-image. The images they have about their bodies come from the experiences they have and from the feedback from family, peers, teachers, and others in the community. This feedback clarifies their understandings and allows the child to gain in self-confidence and feelings of worth (see Chapter 16).

Coping Skills

Many schools lack resources to maintain small class sizes or offer special programs for children with learning difficulties. As a result, children with learning problems are passed on from grade to grade without remediation and with the stigma of failure. Children with chronic illnesses or disabilities may have trouble adapting during the school-age years and may need special help to foster independence and a sense of self-esteem. The child’s physical differences may lead to isolation and rejection by peers. Academic success may be difficult if the child is also cognitively impaired, or if the condition limits exposure to opportunities for cognitive development. Latchkey children with chronic illnesses are especially vulnerable because they may need to make decisions about a health care situation without adult advice. Such children need to understand their illness, medications, where to go for emergency care, how to write down instructions or messages, and how to follow important rules. Children mature at different rates in their ability to manage their self-care throughout the school-age years. A child’s capacity for self-care of chronic illnesses depends on the illness, its stability, the child’s age and cognitive skills, and the child’s support network.

Cognitive Development

In early childhood, children transition from preoperational thinking that uses intuitive problem-solving to early concrete operational thinking. One of the signs of school readiness at this age is the presence of logical thought processes (Box 7-1). Magical thinking and egocentric logic fade, and concepts of conservation, transformation, reversibility, decentration, seriation, and classification emerge. Children’s ability to mentally manipulate the world, relationships, and viewpoints of others is facilitated when they have the opportunity to physically manipulate concrete materials (e.g., using paints, paper, and glue; building things; making dams and forts of mud, snow, or rocks).

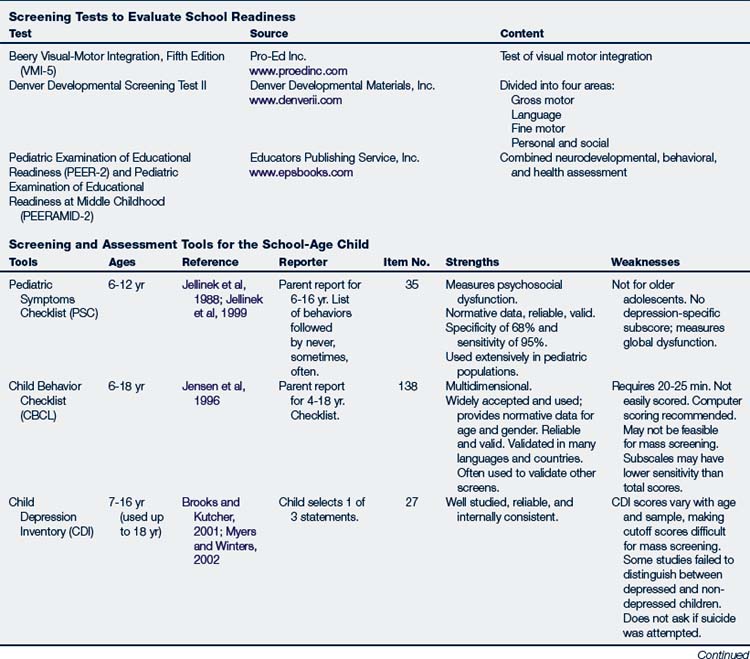

BOX 7-1 Screening and Assessment

Screening Tests to Evaluate School Readiness

| Test | Source | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Beery Visual-Motor Integration, Fifth Edition (VMI-5) | Test of visual motor integration | |

| Denver Developmental Screening Test II | ||

| Combined neurodevelopmental, behavioral, and health assessment |

By middle childhood, children need to understand relationships of mass and length and multiple variables relating to objects. School-age children normally classify or group materials in relation to other information they have. By late childhood, children have well-developed concrete operational thinking. They should be able to focus on more than one aspect of a problem and use logical thinking. For effective cognitive work, young people must process information, recognize salient cues in the environment, organize their thoughts, consider relationships with other information, use short- and long-term memory retrieval and storage skills, make decisions based on the analysis of information, take action, and use feedback to further their learning.

Developmental Assessment of School-Age Children

Developmental Assessment of School-Age Children

Developmental surveillance (see Chapter 4) is an essential aspect of each contact with the school-age child because visits are less frequent during the school years. Most visits are for minor acute illnesses rather than health maintenance. Data must be collected on the child’s physical, nutritional, neurodevelopmental, psychosocial, behavioral, and emotional status during these visits. As with all children, assessment of the family system is crucial. For the school-age child, it is particularly important to evaluate how well the family nurtures the child while supporting the child’s efforts to separate, become more independent, and create a unique self in the community.

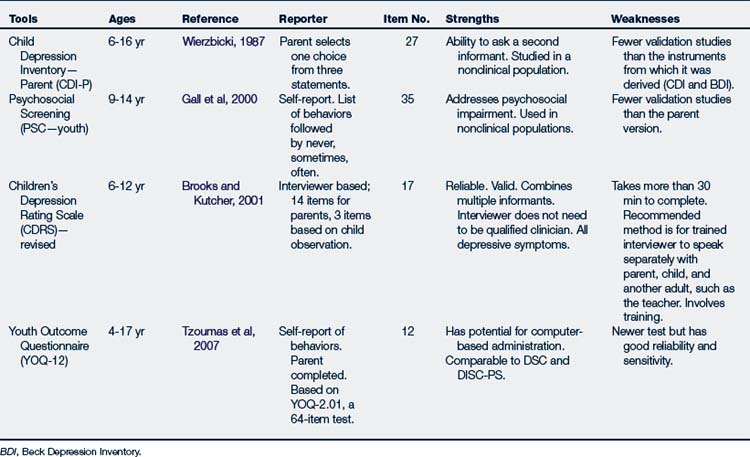

Screening Strategies for School-Age Children

Formal developmental screening tools and/or questionnaires should be used with all children (Hagan et al, 2008). These tools allow the child, parent, and teachers to provide specific information about a child’s development, behaviors, and emotional status. They also document a baseline status, highlight potential need for referrals, and evaluate the effectiveness of intervention strategies. Differing parental, school, and child perceptions about specific issues may be noted. Parental reports of skills and concerns about language, fine motor, cognitive, and emotional-behavioral development are highly predictive of true problems. The information gives the provider insights into areas needing further investigation and those that may require counseling, therapy, or other intervention strategies. In addition, the Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (3rd edition) recommends annual routine health visits for children from 5 through 12 years (Hagan et al, 2008).

Physical Development

Physical development is assessed through history taking, physical examination, and documentation of findings (Table 7-3). Growth measurements (weight, height, BMI) and blood pressure should be evaluated and compared with age-appropriate norms at each visit. Hearing and vision should be screened at routine health visits. Hemoglobin or hematocrit is done during early childhood (between 15 months and 5 years) and again during late childhood (about 13 years); girls should be screened again after beginning menstruation. Perform fasting glucose, insulin, lipid analysis; total cholesterol, and liver function tests to assess for diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic syndrome in children 4 years or older with a BMI equal to or greater than 95% or if BMI is greater than 85% and other risk factors are present such as family history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Lead screening should be conducted if no previous screen has been done, if a previous screen was positive, or if there is a change in risk factors (see Fig. 41-5 for lead screening criteria). Likewise, a tuberculin skin test should be performed if screening indicates risk factors (see Chapter 23). Review immunization status at all visits and update immunizations as appropriate. Tanner staging should be done at all visits because school-age children can begin pubertal changes as early as 8 years old, and some endocrine problems may emerge in the school years (see Chapters 8 and 25). If a child does not have a regular dentist, oral health screening and referral to a dental home are indicated.

TABLE 7-3 Guidelines for the History and Physical Examination of the School-Age Child

| Assessment Area | Findings |

|---|---|

| Chief Complaint | Main concern (e.g., school performance: inattention, fidgeting, difficulty completing tasks, stays on tasks forever, forgetful, angry, frustrated, poor academic performance, moody, irritable, talks excessively) |

| Subjective Data and History | |

| Birth history | Early development, including feeding, sleep-wake cycles, colicky or fussy baby, poor suck; Apgar scores; length of hospitalization; oxygen or phototherapy |

| Past medical history | Illnesses that may explain the child’s problems (e.g., otitis media, chronic illness, vision problems, dental problems, food allergies, reflux, voiding and stooling issues, undiagnosed pain); chronic conditions such as asthma, congenital cardiac conditions, accidents, injuries, hospitalizations, or surgeries |

| Allergies | Type of allergies and reactions |

| Past development | Age attained early developmental milestones, especially language and social skills |

| Interim history | Onset of problem; description of when it occurs; note child’s use of alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes; review of systems related to any chief complaint; any medications taken for acute or chronic conditions |

| Daily activities | Daily sleep-wake pattern, routines and schedule, amount of passive activities (TV and computer) vs. active play and recreational activities; note family routines, family activities, family expectations of the child, and child’s ability to complete chores or jobs around the house |

| Temperament and personality | Identify difficulty with change and transitions, establishing routines, or finishing tasks; difficulty with mood, new situations, making or keeping friends |

| School history | School progress, subjects liked and disliked, peer relationships, match with teacher and school philosophy |

| Family history | Family and home routines and environment, family support systems, activities, involvement in social and school activities, parent’s knowledge of child’s friends and involvement with child’s friends |

| Family review of systems | Family history of medical problems, congenital anomalies, ADHD, learning problems, mental retardation, autism, emotional or psychiatric problems, sleep problems, drug or alcohol abuse, diabetes, obesity, asthma or allergies, domestic violence, criminal activities |

| Objective Data and Physical Examination | |

| Measurements and vital signs | Child’s growth percentiles, especially if below the 5th percentile or above the 85th percentile; note head circumference where appropriate; note BMI and blood pressure and compare with norms for age of child; hematocrit |

| General | Child’s overall appearance, cooperation, parent-child interaction, parent’s responsiveness to the child, and the child’s responsiveness to the parent |

| Skin and lymph | Rashes, lesions, edema, and shape of the nails, hemangiomas, hirsutism, fat tissue, and skinfolds; note enlarged lymph nodes, or mottling of the skin |

| Head, eyes, ears, nose, mouth | Head: Unusual skull shape, hair swirls and unruly hair, and hairline; identify any problems with the temporomandibular joint |

| Face: Flat midface, short mandible, asymmetrical facial movements, and unusual facies, fetal alcohol syndrome facies | |

Eyes: Eye position (hypertelorism/hypotelorism), asymmetries, small epicanthal folds or palpebral fissures; lid: ptosis; conjunctiva: clarity; pupils: PERRLA and cover test, especially for strabismus; EOM: visual fields, nystagmus; fundus: light reflex, vessels, disc, and macula, visual acuity Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |