5 Developmental Management of Infants

Development During the First Year

Development During the First Year

Birth to 1 Month

Physical Development

Newborn assessment begins with a determination of gestational age using the Dubowitz/Ballard exam or similar gestational age scale (see Chapter 38). It is important to document significant prematurity, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and size for gestational age (i.e., either large for gestational age [LGA] or small for gestational age [SGA]). Comparisons are made between the reported gestational age, birthweight and length, and head circumference.

The infant may initially lose up to 5% to 8% of birthweight but should regain it within 10 to 14 days. Weight loss of 10% or more requires close monitoring and may require further evaluation. Weight gain after the initial loss averages 0.5 to 1 ounce (14 to 28 g) per day, or about 2 pounds (1 kg) per month. Nutritional needs to promote growth are about 110 kcal/kg/day (see Chapter 10).

Motor Skills Development

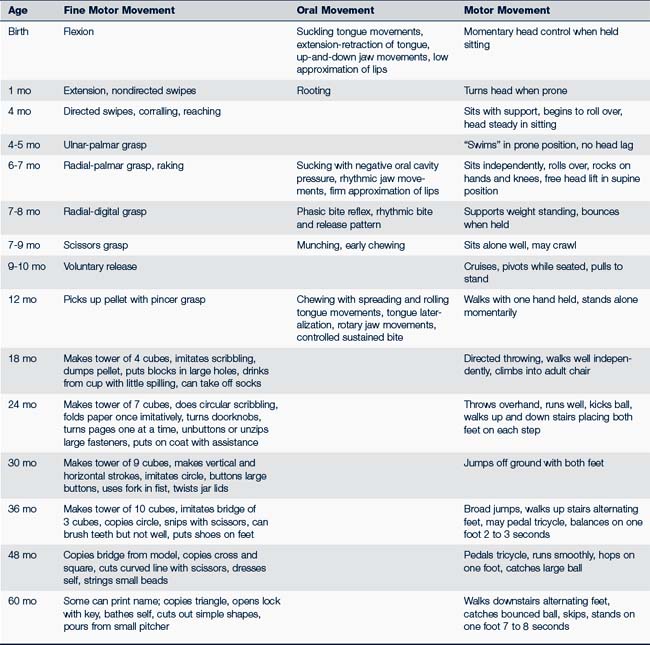

The newborn’s flexed posture provides the infant with the ability to self-console when positioned so that the hands reach the face and mouth. Primary reflexes, such as sucking, rooting, asymmetric tonic neck, Moro, and grasp, should be present and symmetric. Passive muscle tone is evaluated within gestational age scales through observation of shoulder (scarf sign) and knee flexibility (popliteal angle). Arm and leg recoil provide information about the infant’s active movements, particularly symmetry and coordination. Jerkiness and tremors may be noted. The neonatal period begins a remarkable series of fine and gross motor skill milestones for the infant (Table 5-1).

Social and Emotional Development and Maternal Postpartum Depression

Social and emotional development is closely linked to the mother’s emotional state—60% to 80% of mothers experience “baby blues” in the first 2 weeks of life, 10% to 15% have postpartum depression during the first year of the infant’s life, and 0.1% to 0.2% present with postpartum psychosis. Postpartum depression can occur anytime during the first year of the infant’s life, whereas postpartum psychosis generally presents in the first weeks after delivery. The rate of postpartum psychosis is significantly higher if there is maternal schizophrenia or bipolar disease, or when the mother’s history is positive for previous postpartum psychosis (Spinelli, 2009). The pediatric health care provider sees mothers frequently during the infant’s first year of life. Infants’ well-child visits should be used as opportunities to screen mothers and families for factors that can affect the infant’s growth and development including depression and intimate partner violence. A screening tool such as the 10-question Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale can be used to identify mothers needing further evaluation, referral, and close follow-up (Cox et al, 1987; Wisner et al, 2002) (see Chapter 38 for a copy of this scale).

1 Through 3 Months

Motor Skills Development

Fine motor skills begin to emerge as primitive reflexes become integrated. Infants attempt to grasp rattles, fingers, and clothing. They are able to demonstrate visible head control, lifting the head off the bed about 45 degrees when in the prone position and showing little head droop when held in suspension. All normal body movements are symmetric (see Table 5-1).

Communication and Language Development

Parents should be encouraged to notice how their infant looks at them when they are talking and how intently the infant looks at faces, especially during the quiet alert state, the time when the infant is most interactive. Infants “connect” with parents, even if only for a few moments. By talking to their infant during caregiving activities, parents encourage early language development. Infants start to make cooing and babbling sounds, much to the delight of their parents (Table 5-2 lists receptive and expressive language skills for children from birth to 5 years old). However, body movements (e.g., snuggling, turning the head, arching the body) continue to be the primary form of communication, and providers can help parents identify and become more skilled at interpreting their infant’s cues.

TABLE 5-2 Speech and Language Milestones: Areas for Surveillance

| Age | Receptive Language | Expressive Language |

|---|---|---|

| 0-3 mo | ||

| 3-6 mo | ||

| 6-9 mo | ||

| 9-12 mo | ||

| 12-18 mo | ||

| 18-24 mo | ||

| 24-30 mo | ||

| 30-36 mo | ||

| 36-42 mo | ||

| 42-48 mo | ||

| 48-60 mo | Responds to three-action commands |

4 Through 5 Months

Physical Development

Infants 4 through 5 months old usually begin to settle into regular patterns of eating, sleeping, and playing. They sleep 12 to 15 hours a day with five feedings during the day and one during the night. By this age infants begin to sleep through the night without feeding. Somewhere between 4 and 6 months, infants double their birthweight, and slow growth to gain about 5 ounces (140 g) a week. Their length increases about 0.8 inch (2 cm) per month, and head circumference increases about 0.4 inch (1 cm) per month. Growth may appear in spurts although the overall growth chart will show a steady upward curve. Weight gain can be influenced by the amount of play activity and the sleep schedule. Although the infant’s primary source of nutrition comes from breast milk or formula, parents may ask about when to begin feeding solid foods. Many parents introduce some infant cereals by 4 months, but nutritionally, full-term babies need nothing other than breast milk or iron-fortified formula until 6 months old (see Chapter 10). As solid food is added, changes in stool consistency will be noted.

Motor Skills Development

Motor skills progress (see Table 5-1) as the Moro and asymmetric tonic neck reflexes are integrated, and there is no longer the obligation of arm extension with head turning. The Landau reflex emerges. Infants who are given sufficient tummy time generally begin to roll, first from front to back and then from back to front. Head control becomes stronger and more sustained, and there should be no head lag when the baby is pulled to sit. When in the prone position, infants hold their head up at 45 degrees, gradually progressing to 90 degrees for sustained periods of time. The infant learns to sit, first in the tripod stance, then unassisted with the head held erect. When lying supine, infants are able to lift their legs and bring their feet to their mouth. They bear full weight when standing and enjoy bouncing up and down in a parent’s lap. All their body movements should be symmetric.

Communication and Language Development

Infants’ social skills increase and verbal skills become more evident (see Table 5-2). They begin babbling, using vowel sounds, cooing, and laughing quietly and experiment with variations in tone and pitch, such as low-pitched chuckles and deeper laughs. Eventually they laugh out loud, much to the enjoyment of those around them. Infants’ responses to sounds gradually become more localized, and they search for the sound of a bell or rattle.

Oral-motor development is a prerequisite for speech. Throughout infancy oral development progresses from sucking and rooting to rhythmic biting and chewing. Beginning at about 6 months and continuing through 2 years, the child learns to chew by moving the jaw up and down while flattening and spreading the tongue, and to control biting by using rotary jaw movements with lateralization of tongue placement. These motor skills, essential for the production of speech, are among the most complex movements that the young child must master.

6 Through 8 Months

Physical Development

As infants reduce their breast milk or formula intake and add solids to their diet, growth velocity changes. Weight gain slows to 3 to 4 ounces (85 to 110 g) a week, or about 1 pound (0.5 kg) a month; length gains are about 0.5 to 0.6 inch (1.2 to 1.5 cm) per month; and head circumference increases about 0.2 inch (0.5 cm) per month. If concerns about a large head circumference exist, note each parent’s head circumference and graph them to determine percentile for comparison with their infants, and continue to monitor the infant carefully (see Chapter 27 for a discussion of macrocephaly). Teething symptoms can begin at about 6 months as the central incisors emerge and at 8 months when the lateral incisors emerge. The first childhood illness might occur at the same time as teething behaviors start and these events can disrupt the infant’s previous sleep routine.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree