Chapter 8 Developmental Management of Adolescents

Development of Adolescents

Development of Adolescents

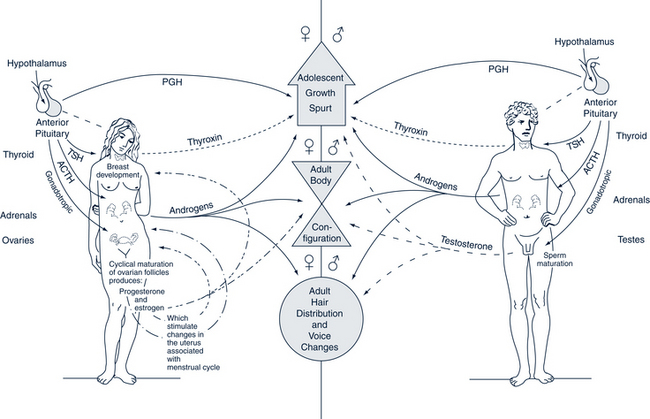

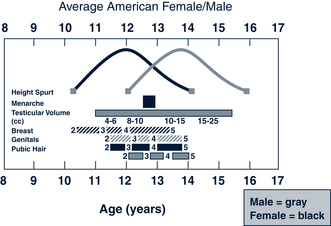

Puberty is the term for the biologic process that ultimately leads to fertility. The hormonal regulatory systems in the hypothalamus, pituitary, gonads, and adrenal glands undergo major changes between the prepubertal and adult states. Accompanying these changes are rapid growth in height and weight, development of secondary sex characteristics, and onset of fertility (Fig. 8-1) (see Chapters 25 and 35). Normal development can be difficult to define and is, at best, an approximation rather than a precise parameter. However, even though the timing (tempo) of adolescent development is variable, the sequence of events is orderly (Fig. 8-2).

Adolescence refers to the psychosocial and emotional transition from childhood to adulthood. The physical changes of puberty are accompanied by significant cognitive and psychosocial development that affects how adolescents view themselves and how the world views adolescents. Successful development in adolescence culminates in achievement of goals that can provide the basis for a healthy and productive adult life (Table 8-1).

TABLE 8-1 Adolescent Development and Related Anticipatory Guidance

| Area of Development | Anticipatory Guidance |

|---|---|

| Physical | |

| Experience growth from prepubescence to sexual maturity | |

| Reach adult parameters of height and physical growth by late adolescence | Provide prevention counseling regarding substance abuse, safety, and unintentional injuries (e.g., bicycle helmet use, seatbelts, gun storage). |

| Become comfortable with one’s body | Offer reassurance that physical findings are normal; explain what to expect; listen to adolescents’ concerns; encourage exercise, sports participation, and body fitness; encourage healthy nutrition. |

| Cognitive | |

| Move from concrete thinking to ability to reason abstractly | |

| Develop personal value system and moral integrity | |

| Move from dependence on others to self for risk reduction | |

| Psychosocial | |

| Establish independence from parents | |

| Develop sense of self-identity | |

| Create new relationships with peers and other adults | Discuss importance of activities with peers; identify healthy ways to be part of a group. Encourage the adolescent to participate in community activities. Provide information and opportunity to discuss questions regarding sexuality, how to differentiate between “love” and “infatuation,” how to be sexually responsible, and how to protect against pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. |

Physical Development

Tanner Stages

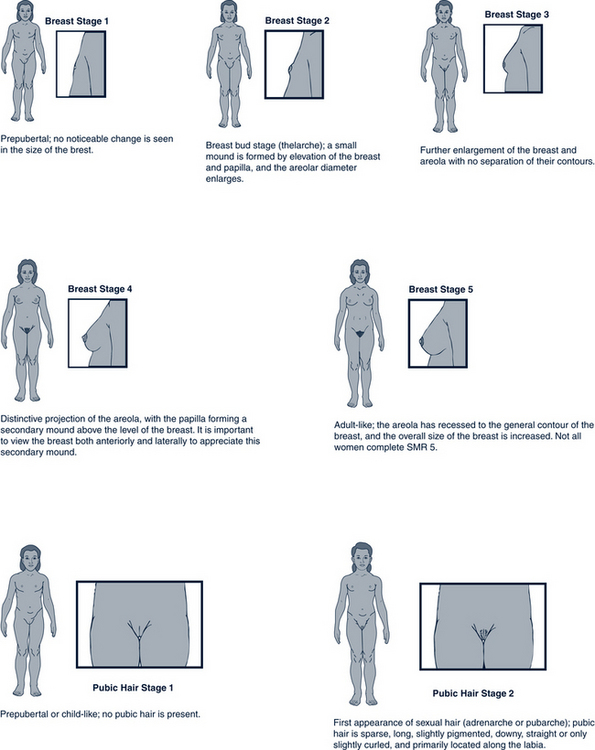

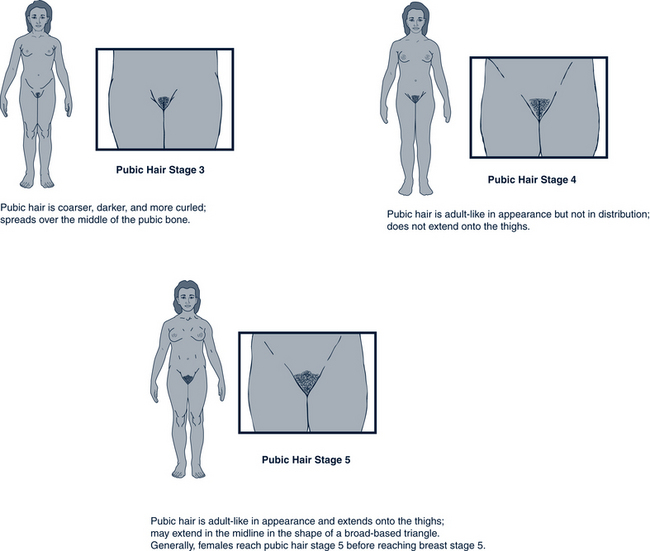

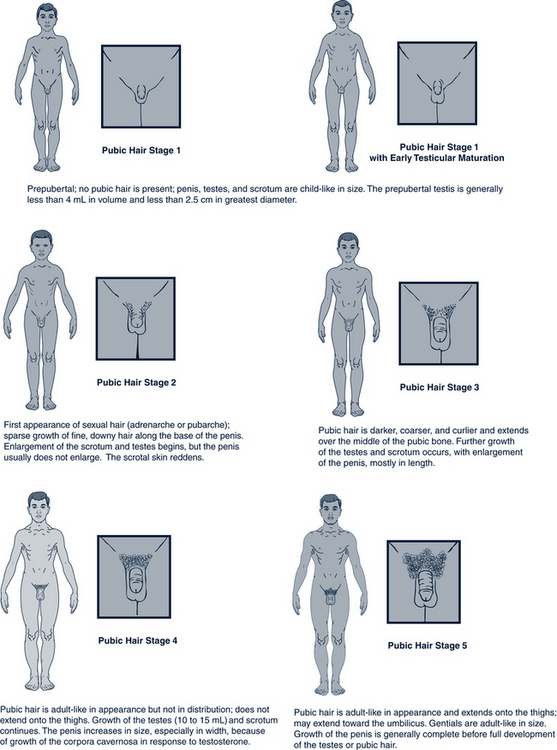

Pubertal growth and maturation can be divided into five stages ranging from prepubertal (sexual maturity rating [SMR] 1) to adult (SMR 5). These divisions are termed Tanner stages (Tanner, 1962) (Figs. 8-3 and 8-4). Pubertal changes occur on a continuum, with individual differences in timing or tempo.

FIGURE 8-3 Tanner stages: female. SMR, Sexual maturity rating.

(Adapted from Division of Adolescent Medicine, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, 1995.)FIGure 8-3, cont’dTanner stages: female.

FIGURE 8-4 Tanner stages: male. SMR, Sexual maturity rating.

(Adapted from Division of Adolescent Medicine, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, 1995.)

Female Stages

• Ovaries increase in size; no visible body changes occur.

• Breast budding (thelarche) traditionally occurs between 9 and 10 years old, with 95% of normal girls having initial breast development between 9 and 13 years old (Hagan et al, 2008). Evidence indicates that adolescent girls are entering and completing puberty younger than girls did 50 years ago (Euling et al, 2008). Most girls (85%) experience the development of breast buds approximately 6 months before the appearance of pubic hair. Girls of African descent are more likely to develop pubic hair (adrenarche) before or at the same time as breast budding, whereas Caucasian girls typically have thelarche before adrenarche (Herman-Giddens, 2006). The timing of onset of breast development in females has no relationship to breast size at the completion of puberty.

• Rapid linear growth usually begins shortly after the onset of breast budding and reaches its peak about a year later. Most girls experience peak height velocity (PHV) about 6 to 12 months before menarche, generally between 11 and 12 years old, and PHV is completed by about 13 years old. Early developers may experience a height spurt between 9 and 10 years old, whereas late developers may not experience a height spurt until between 13 and 14 years old. Final height is determined by the amount of bone growth at the epiphyses of the long bones. Growth stops when hormonal factors shut down the epiphyseal plates.

• Appearance of pubic hair (adrenarche or pubarche) commences at about 11.5 years old and is related to adrenal rather than gonadal development, not to thelarche; therefore, it is less valid than other secondary sex characteristics in assessing sexual maturation.

• The first menstrual period (menarche) occurs, on average, at 12.5 years old. More than 95% of girls experience menarche between 10.5 and 14.5 years old. The mean age of menarche is highly dependent on ethnic, socioeconomic, and nutritional factors. Menarche generally occurs 1.5 to 2.5 years after thelarche. It may be 18 to 24 months after menarche before females establish regular ovulatory cycles. To some degree, menstrual cycles can be affected by the athletic activity of the female. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommend that health care providers recognize the menstrual cycle as a “vital sign” because of the need for education regarding normal timing and characteristics of menstruation and other pubertal signs (Hagan et al, 2008).

Changes in the body composition of females occur during puberty, and adolescent girls will benefit from the primary health care provider’s reassurance that these changes are normal. Initial breast development usually begins as a unilateral disk-like subareolar swelling, and many adolescents and parents may initially present with concerns about breast tumors. Girls often have asymmetric breasts and need assurance that breasts become more or less the same size within a few years after the onset of breast budding. The female body shape changes as girls progress through puberty, with broadening of the shoulders, hips, and thighs. Girls experience a continuous increase in proportion of fat to total body mass during puberty. They enter puberty with approximately 80% lean body weight and 20% body fat. By the time puberty ends, lean body mass drops to about 75%. Body fat is an important mediator for the onset of menstruation and regular ovulatory cycles. An average of 17% of body fat is needed for menarche, and about 22% is needed to initiate and maintain regular ovulatory cycles.

Male Stages

Physical body changes of puberty generally occur sequentially in males as follows:

• The initial sign of male puberty is testicular enlargement, on average at age 11 (Hagan et al, 2008). Growth of the testes occurs approximately 6 months before the development of pubic hair in most males. If testicular enlargement does not precede other changes, the provider should consider whether the boy is taking exogenous anabolic steroids. Once puberty begins, the left testis generally hangs lower than the right.

• Pubic hair development follows a pattern similar to that of girls (see Fig. 8-4).

• First release of spermatozoa (spermarche) generally occurs in midpuberty at a mean age of 13.5 to 14.5 years. However, it can occur at any stage of development from SMR 2 to 5.

• Elongation and widening of the penis usually begin in SMR 3 and continue through SMR 5 (see Fig. 8-4).

• Rapid growth in height occurs. The PHV for males tends to occur late in middle puberty to early in late puberty. Boys generally lag about 2 years behind girls, but the height spurt can begin as early as 10.5 years or as late as 16 years. Males typically have a higher peak growth velocity than females. One fifth of normal adolescent males do not reach their PHV until SMR 5, and there is some evidence that late maturers may achieve greater PHV (Sherar et al, 2005). Males can continue to grow, although minimally, well beyond their teenage years.

• Change in the male voice occurs; this coincides with the PHV.

• Development of axillary, facial, and body hair occurs. Axillary hair generally does not appear before SMR 4 pubic hair. Facial hair appears only after SMR 4 pubic hair and does so in an ordered sequence. It starts at the outer corners of the upper lip and moves inward, then appears on the upper parts of the cheeks and middle of the lower lip, and finally grows along the sides and lower border of the chin. The extent of body hair is determined to a large extent by genetic factors. Body hair develops gradually after facial hair. Body hair changes should not, however, be used to assess pubertal maturation related to changes in the endocrine system.

As with girls, the body composition of adolescent boys changes, sometimes causing great concern for the adolescent. The provider can be an invaluable source of information and reassurance. In contrast to females, males generally increase muscle mass and lose body fat during puberty.

Psychosocial, Emotional, and Cognitive Development

Principles of Adolescent Psychosocial, Emotional, and Cognitive Development

• Feel a sense of belonging in a valued group

• Acquire skills and master tasks that are important to the valued group

• Develop a sense of self-worth

• Develop at least one reliable relationship with another individual

The adolescent’s ability to achieve these goals depends in part on brain functioning. Although full sized, the adolescent brain continues to develop functional ability. In particular the prefrontal cortex, which coordinates executive functions of abstract thinking, reasoning, judgment, self-discipline, ethical behavior, personality, and emotions, experiences rapid growth. As with the infant brain, a process of pruning and reinforcement occurs, based on the stimuli, activities, and experiences of the teenager.

Suicide and homicide are also risks for adolescents. Although motor vehicle accidents and unintentional injuries are the major causes of adolescent mortality, 14.5% of teens in grades 9 to 12 across the country have seriously considered suicide, and 12% of deaths in the ninth- to twelfth-grade age group are due to suicide. Data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicate that in 2009 13.8% of these teens had seriously considered suicide; 10.9% made a plan, and 6.3% attempted suicide (Eaton et al, 2010). Particularly vulnerable are younger (ninth grade), white and Hispanic girls. Depression is a contributing factor to suicide and is discussed in Chapter 19. Homicide represents 16% of all teenage deaths (Eaton et al, 2010).

• Transition is continual and generally smooth.

• Disruptive family conflict is not the norm.

• The quality of thinking changes from concrete to formal operational thinking.

Family Relationships Change

The second principle of adolescent psychosocial development is that the biologic, cognitive, and emotional changes experienced by adolescents require a reworking of family relationships. Some degree of adolescent-parent conflict is to be expected because of this reworking of relationships, but disruptive family conflict is not the norm. Mundane, everyday issues such as which clothes to wear, hairstyles, household chores, curfew, and friends continue to be the usual sources of parent-adolescent conflict, and negotiation between parent and child is essential. Inexperienced in negotiation, adolescents will often argue a point to excess. It may help to remind parents that this verbal debate, or “arguing,” is a normal behavior of teens that reflects their use of more abstract thinking skills. It is a way of practicing abstract thinking and engaging parents. However, the parent should not become too deeply engaged because the adolescent rarely is, and the “arguments” tend to blow over fairly quickly (Box 8-1).

BOX 8-1 Tips for Parents: Adolescent Survival Guide

• Start with clear rules and expectations before children are teenagers. Work on developing good communication with children early and continue through adolescence. State expectations and future consequences before trouble has occurred (e.g., before the dance, not when the teen comes home late).

• Try to be flexible and allow teenagers to negotiate. Discussing principles and negotiating solutions are valuable life skills for the future. Do not negotiate rules that are nonnegotiable.

• Fighting and arguing are typical, often used by teens as they practice their developing reasoning skills. Often teens are engaged more recreationally than emotionally. Therefore, when the parent is tired, disengage and walk away. Try not to take what they say personally.

• Teenagers want parents to be involved, concerned, and ask questions. They just may not know it or know how to express their desire.

• Know who their friends are and call those parents from time to time. Compare household rules if possible.

• Be involved at their school if possible. Try to meet their teachers and stay in contact with them.

• Continue to involve teenagers in family activities, even when they no longer want to. Bringing friends along will help.

• Keep promises made to teens. This builds trust and respect and makes you a role model.

• Model good behavior. Adolescents recognize the hypocrisy of saying one thing and doing another.

• Don’t forget that teenagers still need adult supervision at times.

• Keep communication lines open and don’t be afraid to start conversations. Adolescents sometimes want to talk to adults but are nervous about speaking first.

Families should not be experiencing one crisis after another. If family crises are the norm, one should be concerned. When true turmoil exists, it usually represents psychopathology and will not be simply “outgrown.” Careful assessment and treatment are required. Behavior that results in negative consequences is cause for concern (e.g., red hair dye grows out, but being expelled from school has long-term consequences).

Cognitive Changes

• Consider values. The ones they challenge most are those with which they are most familiar, ones they have grown up with.

• Understand concepts of good and evil and understand human nature (e.g., not all authority figures are good people).

• Be aware of contradictions between what is said and what is done (e.g., adolescents are acutely aware when parents tell their children not to smoke or drink even though they do, or when they tell them to wear their seat belts although the parent does not).

• Understand the significance of their place within the construct of time (past, present, future) and begin thinking about what they will be doing in the future (e.g., college, technical school, job, marriage, and family).

Egocentrism of Adolescents

• Imaginary audience: Everyone is thinking about them.

• Personal fable: They are special.

• Overthinking: They make things more complicated than they are.

• Apparent hypocrisy: Rules apply differently to them than to others.

Personal Fable

The second type of egocentrism is the personal fable. If everyone is watching you and thinking about you (thanks to the imaginary audience), you must be someone special. The personal fable is the concept that the laws of nature do not apply to oneself and that one’s thoughts and feelings are totally unique. The personal fable has a very positive aspect in that it provides adolescents with a sense of importance, purpose, and hope; it helps them to imagine possibilities and opportunities in their lives and futures. Personal fables can also have a negative effect (e.g., when adolescents believe that they will never grow old, cannot get pregnant [especially the first time], cannot get a sexually transmitted infection despite engaging in unprotected intercourse, or will not suffer long-term consequences from substance use).

Developmental Screening and Assessment

Developmental Screening and Assessment

Approaches to Assessment of Adolescents

The American Medical Association (AMA) has developed a thorough interview format for teens in their published AMA Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services (GAPS) program (Elster and Kuznets, 1994), and basic health assessment of adolescents is discussed in Chapter 2. The HEEADSSS technique can be used to assess risk behaviors of adolescents and includes items that reflect the health issues that cause the greatest morbidity and mortality in adolescence (see discussion later in this chapter).

For teenagers who are hesitant to discuss sensitive issues, a questionnaire or checklist may be an effective way to collect information. Questionnaires used to identify adolescent strengths have also been created by the Search Institute and have been used by communities to enhance adolescent self-concept (see Chapter 16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree