4 Developmental Management in Pediatric Primary Care

This chapter presents an introduction to principles of development, developmental theories, methods of developmental assessment, and identification and management of developmental problems. Chapters 5 through 8 review developmental theories, describe normal patterns of development, identify “red flags” related to development, and recommend anticipatory guidance for families of infants, toddlers and preschoolers, school-age children, and adolescents.

Developmental Principles

Developmental Principles

Principle 3. Development occurs in a cephalocaudal and proximodistal direction. An example of this principle is seen as infants develop increasing motor coordination, gaining head control before sitting and walking. Similarly, developmental progress is seen in controlled movements that occur first near the midline of the body, such as rolling over. Eventually distal coordination of the hands, such as mastery of the pincer grasp, occurs.

Developmental Theories

Developmental Theories

Cognitive-Structural Theories: Language and Thought

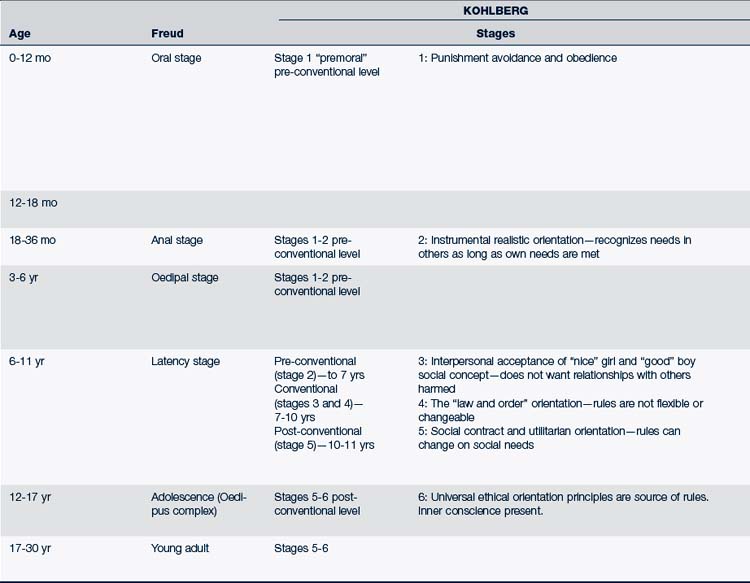

Jean Piaget’s observations, many of which were of his own children, provide an understanding of children’s cognitive development and their perception and interaction with the world around them. Piaget (1969) described how children actively use their life experiences, incorporating them into their own mental and physical being over time. He emphasized how children modify themselves depending on their environmental experiences and their stage-related competency level. Piaget described four stages of cognitive development (Table 4-1).

Formal Operational Stage (13 Years through Adulthood)

At this stage, children begin to think abstractly and imagine different solutions to problems and different outcomes. Adolescents begin to develop increased awareness of degrees of illness and personal control of one’s health. Renewed egocentrism may be noted early in this stage as a result of a lack of differentiation between what others are thinking and one’s own thoughts. This egocentric thinking eventually gives way to an appreciation of the differences in judgment between the adolescent and other individuals, societies, and cultures. It becomes the basis of an adolescent’s ability to think about politics, law, and society in terms of abstract principles and benefits rather than focusing only on the punitive aspects of societal laws.

Kohlberg (1969) focused on theories of moral development and socialization, emphasizing the process by which children learn the expectations and norms of their society and culture (see Table 4-1). Kohlberg’s work primarily involved male participants. Gilligan (1982) suggested that female thoughts and actions involve significantly different objectives and goals, specifically that girls tend to think more in terms of caring and relationships, basing their moral judgments on complexities they perceive in human interactions.

The Role of Social Interaction in Cognitive Development

Vygotsky believes that children learn by watching adults and other children and that children learn best when their parents and caregivers provide them with opportunities in the child’s zone of proximal development. This theory holds that cognitive development occurs in a social, historical, and cultural context, and that adults guide children to learn. Development depends on the use of language, play, and extensive social interaction. One of Vygotsky’s examples is the process of the child learning to point his or her finger. Initially, the infant points his or her finger without meaning; however, as people, and especially caregivers, respond to the finger pointing, the infant learns there is meaning to the movement. What starts as a muscle movement becomes a means of interpersonal connection between two people (Vygotsky, 1978). This theory further holds that play and learning should be constructed to take into consideration the child’s needs, inclination, and incentives. This theory supports the benefit of adult social learning opportunities via group interaction and observation.

Psychoanalytic Theories

Personality and Emotions

Psychodynamic theorists study factors that influence the emotional and psychological behavior of individuals. Personality includes the characteristics of temperament and motivation, in addition to concepts related to self-esteem and self-concept. Sigmund Freud (1938) was one of the most influential theorists in this area. Freud sought to find links between the conscious mind and the body through the unconscious mind (see Table 4-1). Some of his most significant contributions were his descriptions of the interactions of id, ego, and superego (Thomas, 1985).

Erikson (1964) expanded Freud’s theories, describing the stages of the individual throughout the life span (see Table 4-1). Each stage presents problems that the individual seeks to master. Erikson believed that if problems were not resolved, they would be revisited again at future stages.

Behavioral Theories: Human

Actions and Interactions

Behaviorism, the study of the general laws of human behavior, focuses on the present and ways that the environment influences human behavior. Skinner’s view of child development examined learning that was controlled through classic operant conditioning (1953). Behavior modification therapy is largely based on Skinner’s work. Bandura’s social learning theory looked at imitation and modeling as a means of learning, emphasizing the social variables involved (Mott, 1990; Thomas, 1985). Bijou and Baer (1965) responded to critics of behaviorism’s view of the child as a passive object, arguing that children’s responses to environmental stimuli are dependent on their genetic structure and personal history (Thomas, 1985).

Temperament

The work of Chess and Thomas (1995) explains the role that temperament plays in children’s behavior. They identified characteristics or qualities of temperament and introduced the concept of “goodness of fit” to describe the degree to which the child’s environment and parents’ characteristics, including the parents’ temperament, are congruous with the child’s natural temperamental characteristics. Understanding the child’s unique temperament prepares the health care provider to help parents and other caregivers to better understand the child’s behavior, especially when the behavioral reactions are confusing or problematic for the parents. The provider can discuss with parents their view of their child’s temperament, how it “fits” with the parents’ temperament or that of other family members, and what parent-child strategies can be used if conflicts emerge between the child’s temperament and the caregivers’ personal style. The intent is to alleviate guilt and frustration and to assist parents to develop skills that enhance positive behaviors rather than exaggerate difficult temperamental characteristics. Being able to support both the parent and child’s needs can prevent significant problems later on. Table 4-2 further defines characteristics of temperamental differences.

TABLE 4-2 Characteristics of Temperament

| Temperament Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Activity | What is the child’s activity level? Is the child moving all the time he or she is awake, some of the time, or rarely? |

| Rhythmicity | How predictable is the child’s sleep-wake pattern, feeding schedule, and elimination pattern? |

| Approach or withdrawal | What is the child’s response when presented with something new such as a new toy, a new experience, or a new person? Does he or she immediately approach or turn away? |

| Adaptability | How quickly does the child get used to new things? Quickly or not at all? |

| Threshold of response | How much stimulation does the child require for calming? A quiet voice and touch or more intense, loud voice or firm grasp? |

| Intensity of reaction | Are the child’s responses (crying or laughing) very subtle or extremely intense? |

| Quality of mood | Is the child’s mood usually outgoing, happy, joyful, pleasant or unfriendly, withdrawn, or quiet? |

| Distractibility | How easily is the child distracted by outside disturbances such as a phone ringing, TV, siblings? |

| Attention span and persistence |

Self-Regulation

Self-regulation involves a transition from mutual regulation between mother and newborn and emphasizes the importance of both “nature and nurture” in a child’s development (Shonkoff and Phillips, 2000; Trevarthen and Aitken, 2001). Examples of self-regulation are early infant sleep patterns and the ability to self-soothe, the toddler’s ability to manage emerging emotions, the preschooler’s ability to transition from home to school, the school-age child’s ability to focus attention on important tasks, and the adolescent’s sense of confidence and competence. Learning self-regulation is influenced by differences in temperament, genetics, child abilities, and characteristics of the child’s environment (Kochanska et al, 2001). The ways in which the social environment interacts with the individuality of the child and the types of interventions that will contribute to successful self-regulation continue to be explored. One important variable influencing the child’s development appears to be a need for a predictable and consistent environment and a caring, emotionally available caregiver (Bronson, 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree