Chapter 27 Developmental Delay

Suspected

“Doctor, shouldn’t he be talking already?”

“Our daughter seems slower than her classmates. We’re concerned.”

ETIOLOGY

What Functional Deficits Occur in Developmental Delay?

A child with developmental delay has deficits in one or more of the following functions:

Input, or receiving information from the environment

Input, or receiving information from the environment

Processing, or breaking information into usable components

Processing, or breaking information into usable components

Output, or using the components to interact with the environment

Output, or using the components to interact with the environment

A problem in one area can affect ability in another. For example, the input problem of sensorineural hearing loss can diminish the processing ability to understand the nuance of spoken language, even after the loss is treated. A specific disability can cause deficits in all three functions: Cerebral palsy (Chapter 58), for example, may be associated with the input disorders of strabismus and sensorineural hearing loss; processing problems, including mental retardation and learning disabilities; and output problems of spasticity and contractures.

How Do I Determine the Cause of Developmental Delay?

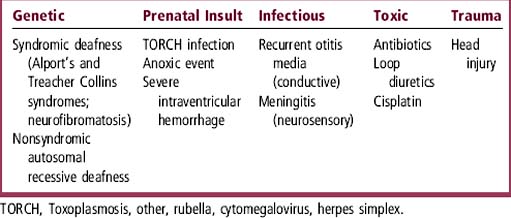

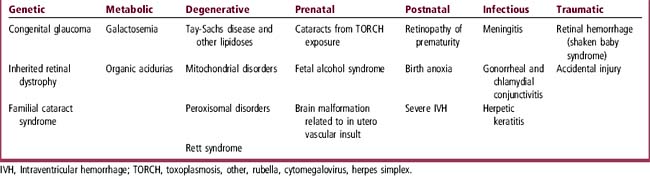

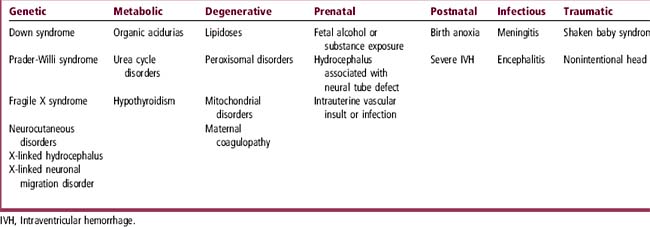

Once you identify the functional deficits, you can begin to think about causes. Tables 27-1, 27-2, and 27-3 indicate the most common etiologies for input and processing deficits. These lists include general categories of disease and the most common causes of developmental delay.

Most input problems consist of hearing loss (Table 27-1) or visual loss (Table 27-2).

Most input problems consist of hearing loss (Table 27-1) or visual loss (Table 27-2).

Processing disorders (Table 27-3) include mental retardation or learning disabilities. These disorders all represent some degree of static or progressive brain dysfunction.

Processing disorders (Table 27-3) include mental retardation or learning disabilities. These disorders all represent some degree of static or progressive brain dysfunction.

Output problems usually bring an infant or child with developmental delay to medical attention. Examples include difficulty with gross motor or fine motor movements, balance, and communication.

Output problems usually bring an infant or child with developmental delay to medical attention. Examples include difficulty with gross motor or fine motor movements, balance, and communication.

EVALUATION

What Should I Ask about Prenatal Events?

A thorough prenatal history obtained using gentle, open-ended questions will lead you to areas that may require more probing. A brief inquiry into the mother’s prepregnancy health will yield information about collagen vascular disease, diabetes, seizure disorder, and other potentially teratogenic health issues. Queries related to the pregnancy itself require particular care, because the mother of a developmentally delayed child often feels at fault for the child’s problems; she may be exquisitely sensitive to any nuance of blame in the interview. In general, however, parents will talk freely if you listen actively and encourage them to tell their story. You can do so by asking about the clinical details outlined in Table 27-4 and about the quality of the pregnancy experience itself: If the mother has given birth before, was this pregnancy easier or harder than the other(s)? Did the mother have the “flu,” a urinary tract infection, or other illnesses during her pregnancy? Did this baby move around more or less than her other babies? What tests did the doctor do? (You may or may not already have this information). Did the mother need to take any special medications or to rest in bed to prevent premature delivery of the baby? The prenatal history should also include inquiry about prescription drugs, over-the-counter medications, and vitamin supplements taken by the mother at any point during the pregnancy. Table 27-5 lists commonly used medications associated with developmental problems. Questions about alcohol, tobacco, and drug consumption during pregnancy should be carefully posed to avoid the appearance of casting blame. If you frame the inquiry neutrally you are more likely to learn what you need to know: “I ask every parent about drinking and use of substances such as pot, cocaine, and meth during pregnancy. Did you use any? And if so, how much?”

Table 27-4 Pregnancy-Related Historical Factors Associated with Developmental Delay

| Maternal Health | Fetal Viability | Labor and Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | Multiple pregnancy | Premature delivery |

| Seizure disorder | “Vanishing twin” syndrome | Prolonged rupture of membranes |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | Placental anomalies | Chorioamnionitis; other reproductive tract infection |

| Evidence of fetal acidosis |

Table 27-5 Prenatal Medications Associated with Developmental Delay

| Medication | Developmental Anomaly |

|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants | |

| Phenytoin | In utero exposure to all of these drugs can cause anomalies, including craniofacial defects, microcephaly, mental retardation, facial and digital anomalies |

| Trimethadione | |

| Valproic acid | |

| Dermatologic agents | |

| Lindane | Mental retardation |

| Isotretinoin | Mental retardation and major birth defects |

| Anticoagulants | |

| Warfarin | Porencephalic cysts |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree