122 Dermatologic Morphology

Basic Structure Of The Skin

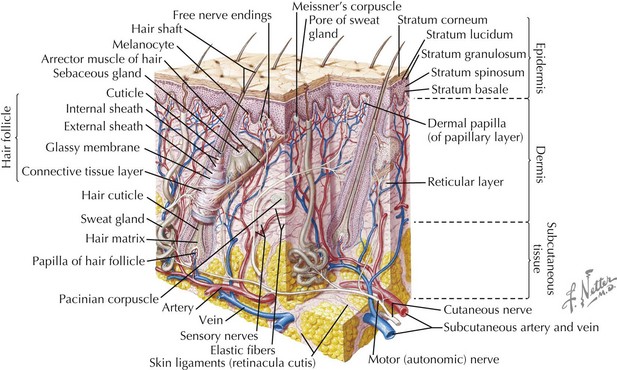

The skin has three basic layers: the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 122-1). Throughout these layers are additional structures and appendages that contribute to the skin’s functionality.

Approach To Dermatologic Morphology And Disease

Primary Lesions

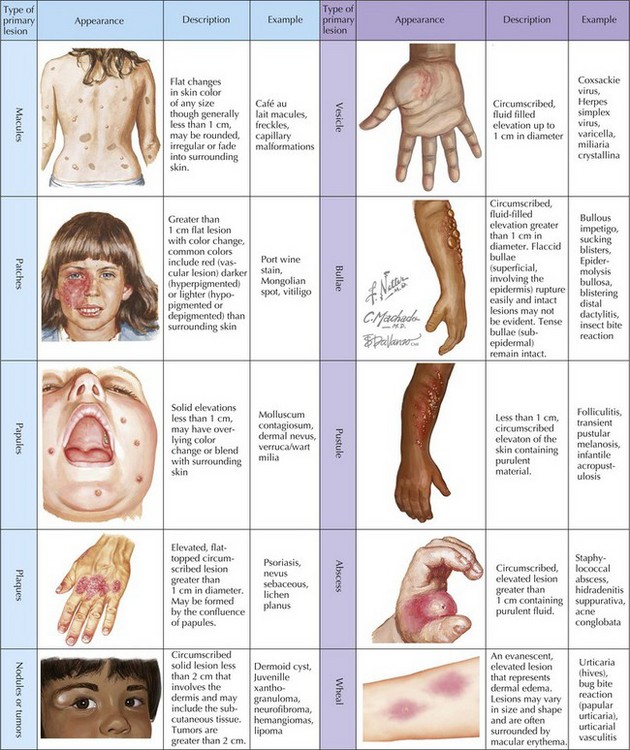

Primary lesions (Figure 122-2) are characterized by their diameter and depth. A macule is a flat lesion that can be seen by changes in skin color but cannot be felt. The border may be well circumscribed or may gradually blend into the surrounding skin. It may be of any size, but the term is generally used to describe lesions smaller than 1 cm. Flat lesions larger than 1 cm are termed patches. Similar to macules, papules are small (<1 cm) lesions but are palpable with the greatest mass above the surface of surrounding skin. Larger elevated skin lesions are termed plaques. Plaques may be formed by a confluence of papules or can be the primary lesion. Palpable, solitary lesions whose mass is primarily below the surface, in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, are termed either nodules (0.5-2 cm) or tumors. Tumors may be benign or malignant.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree