36 Dermatologic Disorders

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

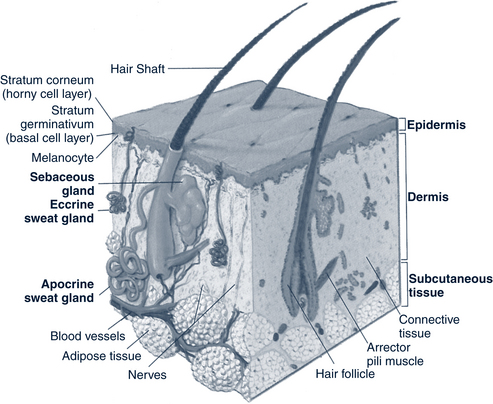

The skin is composed of three layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous layer (Fig. 36-1). Skin, including its epidermis and dermis, varies from 1.5 to 4 mm in thickness (Weston et al, 2007).

FIGURE 36-1 Structure of the skin.

(From Jarvis C: Physical examination and assessment, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1996, Saunders.)

Nails are epidermal cells converted to keratin that grow continually. The nailbed, underneath the nail plate, is composed of layers of epidermis and dermis, which serve as structural support. The nail root lies just under the epidermis.

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms

Pathophysiology and Defense Mechanisms

Disruption of the skin and subcutaneous tissue occurs through a variety of assaults. These include:

• Bacterial, fungal, and viral infections

• Allergic and inflammatory reactions

• Papulosquamous and bullous eruptions

Special Dermatologic Considerations in Children With Dark Skin or from Diverse Cultural or Ethnic Groups

Special Dermatologic Considerations in Children With Dark Skin or from Diverse Cultural or Ethnic Groups

Knowledge of the normal variations in children both with different levels of pigmentation of the skin and from diverse ethnic or cultural groups is important for assessing and treating dermatologic conditions. Skin reactions to injury, inflammation, common skin conditions, and cultural practices are varied. A wise pediatric health care provider listens to parents because they are often the first to detect subtle changes in color or texture of the skin. This section discusses some of the dermatologic differences of children with dark skin.

• Prevent acne or contact dermatitis.

• Immunize against varicella to prevent scarring.

• Use insect repellents to minimize insect bite reactions.

• Treat early signs and symptoms of pruritic or inflammatory conditions (acne, eczema) and infections.

• Use moisturizing agents and eliminate soaps for dry, itchy skin.

• Use oral antipruritics for dry, itchy skin.

• Caution about the use of topical medications, especially high-potency steroids, benzoyl peroxide, and isotretinoin.

Normal Variations and Common Problems

The following are normal variations or common problems in children with dark skin:

• Variation in color and texture of skin from one part of the body to another

• Pigmentation of gingiva, mucous membrane, sclerae, and nails correlates with degree of cutaneous pigmentation.

• Increased areas of melanin in thicker-skinned areas (elbow, knee)

• The term, Futcher’s or Ito line, describe the vertical line that separates the hyperpigmented dorsal and extensor surfaces from less-pigmented ventral surfaces. This line of differentiation follows Voigt lines and is most noticeable on the extremities.

• Mongolian spots and increased numbers of café au lait spots (see later discussion)

• Normal exfoliation produces a fine layer of gray scales.

• Color alterations (jaundice, anemia, cyanosis) are difficult to assess.

• Kinky, wooly, tightly curled hair with closely knit growth that tangles when dry and mats when wet

• Atopic dermatitis (see Chapter 24) with prominent follicular pattern with pityriasis alba and postinflammatory hypopigmentation

Cultural or Ethnic Practices with Skin Sequelae

• Bleaching creams—discoloration and erythematous nodules

• Chemical or thermal hair straighteners—alopecia, fragile hair shaft, scalp contact dermatitis

• Tightly braided, twisted, locked hair (dreadlocks), and tight ponytails—traction folliculitis followed by traction alopecia that can be permanent and cause scarring (Putgen, 2008)

• Henna for superficial tattooing—orange discoloration of skin, increased bilirubin levels in infants

• Decorative practices—scars or tattoos

• Healing practices used during significant illness that produce burns—circular 1- to 2-cm scars on chest, periumbilicus, wrists, ankles, or back

• Coining—petechiae and ecchymoses, especially on chest and back

• Cupping—circular ecchymoses on neck, chest, back, and arms

Assessment of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

Assessment of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

History

The history should assess the following:

Exposures or allergies: Medication, foods, animals, plants? Known allergens? New substances? Persons with similar symptoms or illness? What soaps, hair products (shampoos, gels, pomade, etc.), lotions, and detergents are used?

Exposures or allergies: Medication, foods, animals, plants? Known allergens? New substances? Persons with similar symptoms or illness? What soaps, hair products (shampoos, gels, pomade, etc.), lotions, and detergents are used? All medication (prescription and over-the-counter) taken over the last few days, including creams, ointments, powders, or lotions (it is often helpful to have patients bring medications they have used to the appointment)

All medication (prescription and over-the-counter) taken over the last few days, including creams, ointments, powders, or lotions (it is often helpful to have patients bring medications they have used to the appointment) Skin disorders or history of atopy disorders (asthma, seasonal or drug allergies or atopic dermatitis)

Skin disorders or history of atopy disorders (asthma, seasonal or drug allergies or atopic dermatitis)• Client review of systems and past medical history

Skin, hair, and nails: Skin type (dry or oily), recent and long-term changes, previous incidence of skin disease

Skin, hair, and nails: Skin type (dry or oily), recent and long-term changes, previous incidence of skin disease Eyes, ears, nose, and throat: Swelling, itching, crusting, discharge or circles around eyes, nasal mucus discharge, patency or irritation, dry mouth, lesions, or pain

Eyes, ears, nose, and throat: Swelling, itching, crusting, discharge or circles around eyes, nasal mucus discharge, patency or irritation, dry mouth, lesions, or painPhysical Examination

• Color, color changes, size, and shape

• Arrangement (e.g., isolated, grouped, linear, annular, zosteriform)

• Pattern (e.g., sun-exposed area, symmetry)

• Distribution of lesion (e.g., regional, generalized, crops)

• Border (e.g., indistinct, well circumscribed)

Primary skin lesions (Box 36-1) include changes that arise from previously normal skin. These descriptions should be memorized and used. Secondary skin lesions (Box 36-2) result from changes in primary lesions. Vascular skin lesions (Box 36-3) involve the blood supply. Other useful descriptive terms are listed in Box 36-4. Vesicles, pustules, scaling, and color changes should be noted when considering differential diagnoses.

BOX 36-1 Primary Skin Changes to Lesions

Bulla—vesicle larger than 1 cm

Comedo—plugged, dilated pore; open (blackhead), closed (whitehead)

Cyst—palpable lesion with definite borders filled with liquid or semisolid material

Macule—flat, nonpalpable, discolored lesion, 1 cm or smaller

Nodule—raised, firm, movable lesion with indistinct borders and deep palpable portion, 2 cm or smaller

Papule—solid, raised lesion of varied color with distinct borders, 1 cm or smaller

Patch—macule, larger than 1 cm

Plaque—solid, raised, flat-topped lesion with distinct borders, larger than 1 cm

Pustule—raised lesion filled with pus, often in hair follicle or sweat pore

Tumor—large nodule, may be firm or soft

Vesicle—blister filled with clear fluid

Wheal—fleeting, irregularly shaped, elevated, itchy lesion of varied size, pale at center, slightly red at borders

BOX 36-2 Secondary Skin Changes to Lesions

Atrophy—thinning skin, may appear translucent

Crusts—dried exudate or scab of varied color

Desquamation—peeling sheets of scale

Erosion—oozing or moist, depressed area with loss of superficial epidermis

Excoriation—abrasion or removal of epidermis; scratch

Fissure—linear, wedge-shaped cracks extending into dermis

Keloid—healed lesion of hypertrophied connective tissue

Lichenification—thickening of skin with deep visible furrows

Scales—thin, flaking layers of epidermis

Scar—healed lesion of connective tissue

Striae—fine pink or silver lines in areas where skin has been stretched

Ulcer—deeper than erosion; open lesion extending into dermis

BOX 36-3 Vascular Skin Lesions

Angioma or hemangioma—papule made of blood vessels

Ecchymosis—bruise, purple to brown, macular or papular, varied in size

Hematoma—collection of blood from ruptured blood vessel, larger than 1 cm

Petechiae—pinpoint, pink to purple macular lesions that do not blanch, 1 to 3 mm

Purpura—purple macular lesion, larger than 1 cm

Telangiectasia—collection of macular or raised, dilated capillaries

BOX 36-4 Descriptive Terms for Dermatologic Lesions

Acral—involving extremities (hands, feet, ears, etc.)

Contiguous—touching or adjacent

Diffuse or generalized—scattered, widely distributed

Discrete—distinct and separate

Eczematous—referring to vesicles with oozing crust

Herpetiform—referring to grouped vesicles resembling those of herpes

Iris—arranged in concentric circles, one inside the other

Polycyclic—oval with more than 1 ring

Serpiginous—snakelike, creeping

Symmetric—balanced on both sides

Target lesion—(iris or targetoid) erythematous papule or plaque characterized by a red to violet dusky center surrounded by a raised, edematous pale ring and red periphery

Telangiectatic—referring to dilated terminal vessels

Umbilicated—depressed or shaped like a navel

Zosteriform—resembling shingles, following a nerve root or dermatome

Diagnostic Studies

A few simple laboratory tests are helpful in identifying or excluding dermatologic disorders. Proper procurement of the sample is important. Lesions can be scraped with a no. 15 blade or a toothbrush and scales or debris placed on a glass microscope slide or in culture material. The No. 15 blade is also useful for exfoliating a blister. It is important to scrape under any scabs to get a sample of the organisms. Moistening the lesion may facilitate this. Scrapings can be obtained from the edges of skin lesions, from plucked hair (getting the root is essential), from the nail plate, or from subungual debris. Laboratory tests that can be used include the following:

• Microscopic examination of skin scrapings:

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) can be used to examine for fungal disorders (hyphae or spores; Fig. 36-2). Scrape fine scales from the edge of the lesion onto a glass slide. Add a drop of KOH 20% to dissolve debris, and cover with a coverslip. Let sit for 20 to 30 minutes or heat gently (do not boil). Use × 10 magnification to examine.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) can be used to examine for fungal disorders (hyphae or spores; Fig. 36-2). Scrape fine scales from the edge of the lesion onto a glass slide. Add a drop of KOH 20% to dissolve debris, and cover with a coverslip. Let sit for 20 to 30 minutes or heat gently (do not boil). Use × 10 magnification to examine. Wright, Giemsa, or Gram stains are used to examine for bacteria or herpes simplex or herpes zoster (HZ) giant cells. Allow scrapings to air-dry, then stain with Wright or Giemsa stain. Use × 40 magnification to examine for bacteria.

Wright, Giemsa, or Gram stains are used to examine for bacteria or herpes simplex or herpes zoster (HZ) giant cells. Allow scrapings to air-dry, then stain with Wright or Giemsa stain. Use × 40 magnification to examine for bacteria.• Tzanck smear for herpes, varicella, or zoster

• Microbial culture of lesions for bacteria, viruses, or fungi. Simple, inexpensive culture methods for fungal organisms include the dermatophyte test medium [DTM] and InTray CCD [includes Candida]. Skin or nail scrapings or hairs, including the root, are applied so that they break the agar surface. A color change is noted in 1 to 5 days.

• Patch or skin testing for allergic or contact reactions is usually done by dermatologists or allergists.

• Skin biopsy following local anesthesia may be by punch or shave method for any tumor, palpable purpura, persistent dermatitis, or blister that is not otherwise definitively diagnosed. Such procedures often require referral to a dermatologist.

• Complete blood count (CBC) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) may evaluate infection or inflammation.

Management Strategies

Management Strategies

Hydration and Lubrication

Bathing

Bathing is an efficient means of hydrating and lubricating the skin, especially with dry skin or in dry climates. Lukewarm, not hot, water should be used. The bath should last long enough for skin to become moisturized without becoming supersaturated or “pruned.” Bubble-bath solutions are especially irritating and should be avoided. Soaping and shampooing should be done at the end of the bath followed by thorough rinsing. The skin should be gently dried and a lubricating agent applied immediately. See Chapter 24 for further information on lubricating baths. Baths containing baking soda or colloidal oatmeal may help relieve pruritus. Bathing and other heat exposures can make a rash seem worse temporarily.

Skin Care Agents

Soaps, Oils, and Colloids

Mild soaps are best and include Dove, Aveeno, Neutrogena, Basis, Alpha Keri, and Lubriderm. Cetaphil cleanser and Purpose Gentle Cleansing Wash are soap substitutes. Bath oils include Alpha Keri and Domol. Colloids include Aveeno.

Sunscreens and Sunblocks

Sunscreens and sunblocks protect the skin from UV light and are graded by their ability to provide sun protection. Daily application of a fragrance-free sunscreen with a minimum sun protection factor (SPF) greater than 30 is recommended (American Academy of Dermatology, 2010). Children who are extremely photosensitive should use sunscreen with levels of SPF 30 or higher. Sunscreens that act by absorbing UV light in the B range include para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) or PABA esters, cinnamates, salicylates, benzophenones, and anthranilates. Only benzophenones protect from UV rays in the longer UVA range. Sunblocks, including titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, and talc, scatter light and act as protective barriers. They are especially useful on the nose, ears, and lips (see Box 36-10).

Medications

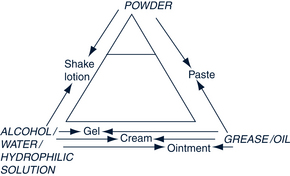

Thought must be given not only to the medication used in treating skin conditions but also its preparation (Box 36-5) and vehicle (Fig. 36-3), including stabilizers, preservatives, and perfumes. Occasionally an individual is sensitive to a medication vehicle or preparation, and symptoms are aggravated rather than relieved. Common agents that cause sensitization include ethylenediamine, lanolin, parabens, thimerosal, diphenhydramine, propylene glycol, “caines,” and neomycin. The following guidelines for use of preparations may be helpful:

• Acute inflammation—wet dressings, powders, suspension lotions, alcohol- or water-based lotions, or aerosols

• Chronic inflammation—creams, oil-based lotions or gels, ointments

• Patient’s tolerance for and willingness to use certain vehicles

BOX 36-5 Preparations of Topical Medications

Creams—contain more water than oil and therefore are less occlusive; better used with less dry skin, in high-humidity areas, in summertime, and on parts of body that naturally cause occlusion (body folds); often accepted better by patient, but must be applied every 2 to 3 hours

Gels—alcohol based, provide good penetration of skin, but can burn on application; primarily used for acne and in hairy areas

Lotions—mixtures of powder and water, useful for drying, cooling, and soothing actions; emulsion lotions contain some oil, so are not as drying as lotions; lotions come in suspension or solution

Oils—fluid fats that hold medication to the skin as barriers or occlusive agents

Ointments—best used with dry skin; composed primarily of oil with little or no water; provide most potent concentration of medication because of their occlusive action on skin; generally need to be used only every 12 hours; tend to leave a greasy feeling and can cause heat retention from decreased evaporation

Pastes—made of a combination of powder and oil, which makes them somewhat difficult to apply and remove, but effective in providing dryness and protection for skin

Powders—absorb moisture and reduce friction, provide cooling, decrease itching, increase evaporation

Shampoos—liquid soaps or detergents for cleaning the hair and skin (e.g., tar for psoriasis or seborrhea, antifungal shampoos for tinea versicolor or tinea corporis)

Antibacterial Agents

Topical antiseptics, soap, and antibacterial soap reduce the number of bacteria on the skin and provide thorough cleansing. Examples of antiseptics include povidone-iodine, chlorhexidine gluconate, and pHisoderm. Topical antibiotics, such as bacitracin, polymyxin B, mupirocin, or retapamulin applied directly to the skin, are used to treat minor skin infections. Products containing neomycin should be avoided because of the high incidence of contact sensitization. Oral antibiotics used to treat more significant bacterial infections include penicillins, erythromycin, cephalosporins, and tetracycline. If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected, obtain a culture and sensitivity of the drainage (see Chapter 23).

Antifungal Agents

Many topical antifungals are over-the-counter medications. Oral antifungals are used for hair and nail infections or refractory skin infections. Because of concerning side effects and minimal clinical experience in children, oral antifungals should be used with caution in children; many of these drugs are not U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for pediatric use (antifungal agents are listed in Table 36-4).

Antiinflammatory Agents

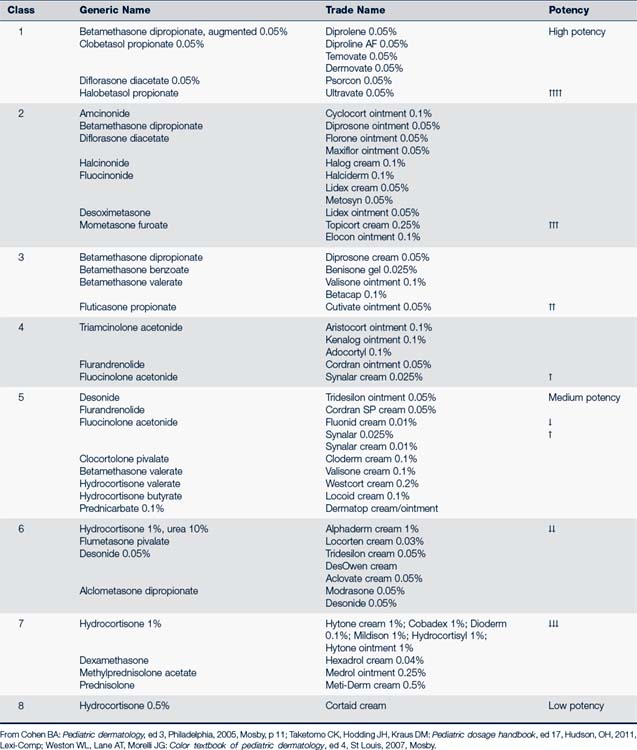

Topical glucocorticoids are frequently used to reduce inflammation, decrease itching, and promote vasoconstriction without causing the widespread systemic effects of oral steroids. They are subdivided into three categories: high potency, moderate potency, and low potency (Table 36-1). It is important to note that steroids are classified as fluorinated or nonfluorinated. Nonfluorinated steroids are less potent and have fewer side effects.

Oral glucocorticoids (prednisone) are used only in acute situations and are limited to short courses. Intralesional steroid injections may be used by a dermatologist to control localized eczema, lichen planus, or psoriasis.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors

This class of immunosuppressive, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory topical medication is used for short-term or intermittent long-term treatment of atopic dermatitis when conventional therapy is inadvisable, ineffective, or not tolerated. Immunomodulators are expensive and cannot be used in children younger than 2 years of age (see Chapter 24).

Bacterial Infections of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

Bacterial Infections of the Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

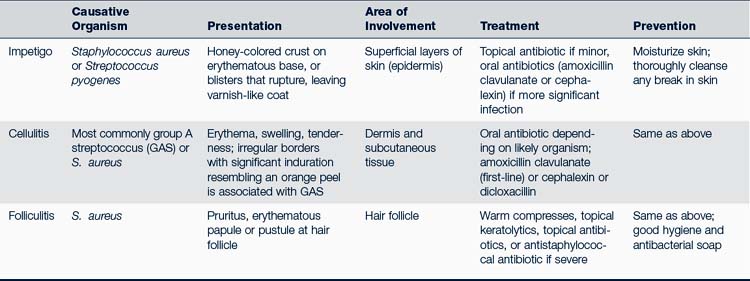

Diagnosis and treatment of common bacterial infections are listed in Table 36-2.

Impetigo

Epidemiology

Bacterial colonization of the skin occurs several days to months before lesions appear; the organism usually spreads from autoinoculation via hands, towels, clothing, nasal discharge, or droplets. Impetigo occurs more frequently with poor hygiene; during the summer months; in warm, humid climates; and in lower socioeconomic groups. Streptococci that cause pharyngitis rarely cause impetigo and vice versa. Secondary bacterial infections of underlying skin problems (dermatitis, varicella, psoriasis) are most commonly caused by staphylococci (Weston et al, 2007).

Clinical Findings

Physical Examination

• Nonbullous, classic, or common impetigo—begins as 1- to 2-mm erythematous papules or pustules that progress to vesicles or bullae, which rupture, leaving moist, honey-colored, crusty lesions on mildly erythematous, eroded skin; less than 2 cm in size; little pain but rapid spread

• Bullous impetigo—large, flaccid, thin-wall, superficial, annular, or oval pustular blisters or bullae that rupture, leaving thin varnish-like coating or scale

• Lesions are most common on face, hands, neck, extremities, or perineum; satellite lesions near the primary site, although they can be found anywhere on the body

Management

Management involves the following:

• Topical antibiotics may be used if the impetigo is superficial, nonbullous, or localized to a limited area. Topical treatment alone provides clinical improvement, but may prolong the carrier state (Weston et al, 2007). Mupirocin and retapamulin are the best choices for topical treatment (Koning et al, 2008; Weinberg and Tyring, 2010; Weston et al, 2007; Yang and Kearn, 2008). Polymyxin B, gentamicin, and bacitracin are less effective (Parish and Parish, 2008).

• Oral antibiotics are recommended for multiple lesions or nonbullous impetigo with infection in multiple family members, childcare groups, or athletes. Treat for S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes because coexistence is common (Cole and Gazewood, 2007; Weston et al, 2007).

• For widespread infection with constitutional symptoms and deeper skin involvement, use an oral antibiotic active against beta-lactamase–producing strains of S. aureus, such as amoxicillin/clavulanate, dicloxacillin, cloxacillin, or cephalexin.

• If an infant has bullous impetigo, use parenteral beta-lactamase–resistant antistaphylococcal penicillin, such as methicillin, oxacillin, or nafcillin.

• If there is no response in 7 days, swab beneath the crust and do Gram stain, culture, and sensitivities. Community-acquired MRSA should be considered. This organism is more susceptible to clindamycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) (see Chapter 23 for treatment of MRSA).

• Educate regarding cleanliness, handwashing, and spread of disease.

• Exclude from daycare or school until treated for 24 hours.

• Schedule a follow-up appointment in 48 to 72 hours if not improved.

Complications

• Cellulitis may occur with nonbullous impetigo and present in the form of ecthyma (infection involving entire epidermis) or erysipelas (spreading cellulitis with induration).

• Lymphangitis, suppurative lymphadenitis, guttate psoriasis, erythema multiforme (EM), scarlet fever, or glomerulonephritis may occur following infection with some strains of Streptococcus. Acute rheumatic fever is a rare complication of streptococcal skin infections.

• Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is a blistering disease that results from circulating epidermolytic toxin–producing S. aureus. SSSS is most common in neonates (Ritter disease), infants, and young children less than 5 years of age. It manifests abruptly with fever, malaise, and tender erythroderma, especially in the neck folds and axillae, rapidly becoming crusty around the eyes, nose, and mouth. Nikolsky sign (peeling of skin with a light rub to reveal a moist red surface) is a key finding. Treatment may include hospitalization and parenteral antibiotics, especially for young children (Berk and Bayliss, 2010). Antibiotics of choice are intravenous (IV) or oral dicloxacillin, a penicillinase-resistant penicillin, first- or second-generation cephalosporins, or clindamycin. Quicker healing without scarring results if steroids are avoided, there is minimal handling of the skin, and ointments and topical mupirocin are used at the infection site (Aronson and Florin, 2009; Berk and Bayliss, 2010). Severe cases may need treatment similar to extensive burn care.

Cellulitis

Description

Cellulitis is a localized bacterial infection often involving the dermis and subcutaneous layers of the skin. It is commonly seen following a disruption of the skin surface from an insect or animal bite, trauma, or a penetrating wound. Cellulitis is more common in children with diabetes and immunosuppression. Periorbital cellulitis is discussed in Chapter 28.

Clinical Findings

History

• A previous skin disruption at the site or recent upper respiratory infection (H. influenzae). Note that edema that occurs within 24 hours of an insect bite is most likely to be inflammatory, whereas edema that occurs between 48 to 72 hours is more likely to be infectious.

• Fever, pain, malaise, irritability, anorexia, vomiting, and chills can be reported.

• Recent sore throat or upper respiratory infection

• Anal pruritus, stool retention, constipation, and blood-streaked stools

Physical Examination

• Erythematous, indurated, tender, swollen, warm areas of skin with poorly demarcated borders

• Blue to purple tinge to the cellulitis is often associated with H. influenzae (Weston et al, 2007)

• Well-demarcated perianal erythema up to 2 cm around the anus. The erythema may extend to the vulva and vagina (Gerber, 2007).

• Erysipelas—a superficial variant of cellulitis—presents with rapidly advancing lesions that are tender, bright red, have sharp margins and an “orange peel” look and feel.

Management

Immediate antibiotic therapy is needed.

• Hospitalization is recommended if the child is a febrile neonate or infant, is acutely ill or toxic, or has periorbital cellulitis.

• Neonates with cellulitis require a full septic workup and initiation of empiric therapy with methicillin or vancomycin and gentamicin or cefotaxime (Morelli, 2007).

Complications

• NF is a rare infection in children and has two subtypes. Type I is generally a polymicrobial infection that usually affects children who have an underlying disease. Type II, commonly referred to as flesh-eating strep, is an acute, rapidly progressing necrotic invasion of GABHS through the skin and subcutaneous tissue to the fascial compartments. It is more common in otherwise healthy children or children with varicella. NF is more common in boys less than 5 years of age and children with diabetes, skin injury, surgery, immunodeficiency, IV drug use, malnutrition, and obesity (Leung et al, 2008; Weston et al, 2007). NF begins as cellulitis (usually on the leg or abdomen in infants) with severe pain, edema, fever, and bullae on an erythematous surface. It quickly progresses to ulcer, eschar, and gangrene within 2 days. Prompt treatment (hospitalization, surgical debridement, and fluid management), prolonged antibiotic treatment (penicillin), and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) may be lifesaving because the overall mortality rate is high.

• TSS is an acute febrile illness with rapid onset that causes significant fever, vomiting and diarrhea, engorged mucous membranes, hypotension, a diffuse macular or sunburn-like rash, conjunctival injection, and multiple organ system involvement. S. aureus or S. pyogenes (group A streptococci) are the causative agents associated with TSS, and incubation can be as little as 14 hours. Both organisms can be associated with invasive infection (e.g., pneumonia, osteomyelitis, bacteremia, or endocarditis) or focal tissue invasion that is rapidly progressive (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2009). Initially recognized in menstruating adolescents, TSS is also found in males and younger children. S. aureus is usually the causative agent in menstruating females. Nasal packing, surgical procedures, and postpartum condition are some factors linked to nonmenstrual TSS. Treatment is intensive, requires hospitalization, and consists of fluid management, antibiotics, and other supportive measures. Staphylococcal TSS has a mortality rate of 3%, whereas streptococcal TSS has a mortality rate of 30% to 60% (Berk and Bayliss, 2010). It is a reportable disease in most states.

Prevention

• Thorough cleansing of any break in the skin helps prevent cellulitis.

• Keep bites, scrapes, and rashes clean and bandaged until healed to prevent them from being infected by staphylococcal bacteria.

• Frequent handwashing is essential; immunize against H. influenzae.

• Perianal spread can occur through shared bath water.

• See Chapter 23 regarding treatment of children and families with MRSA infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree