FIGURE 24-1. Management of depression in pregnancy.

Pharmacologic

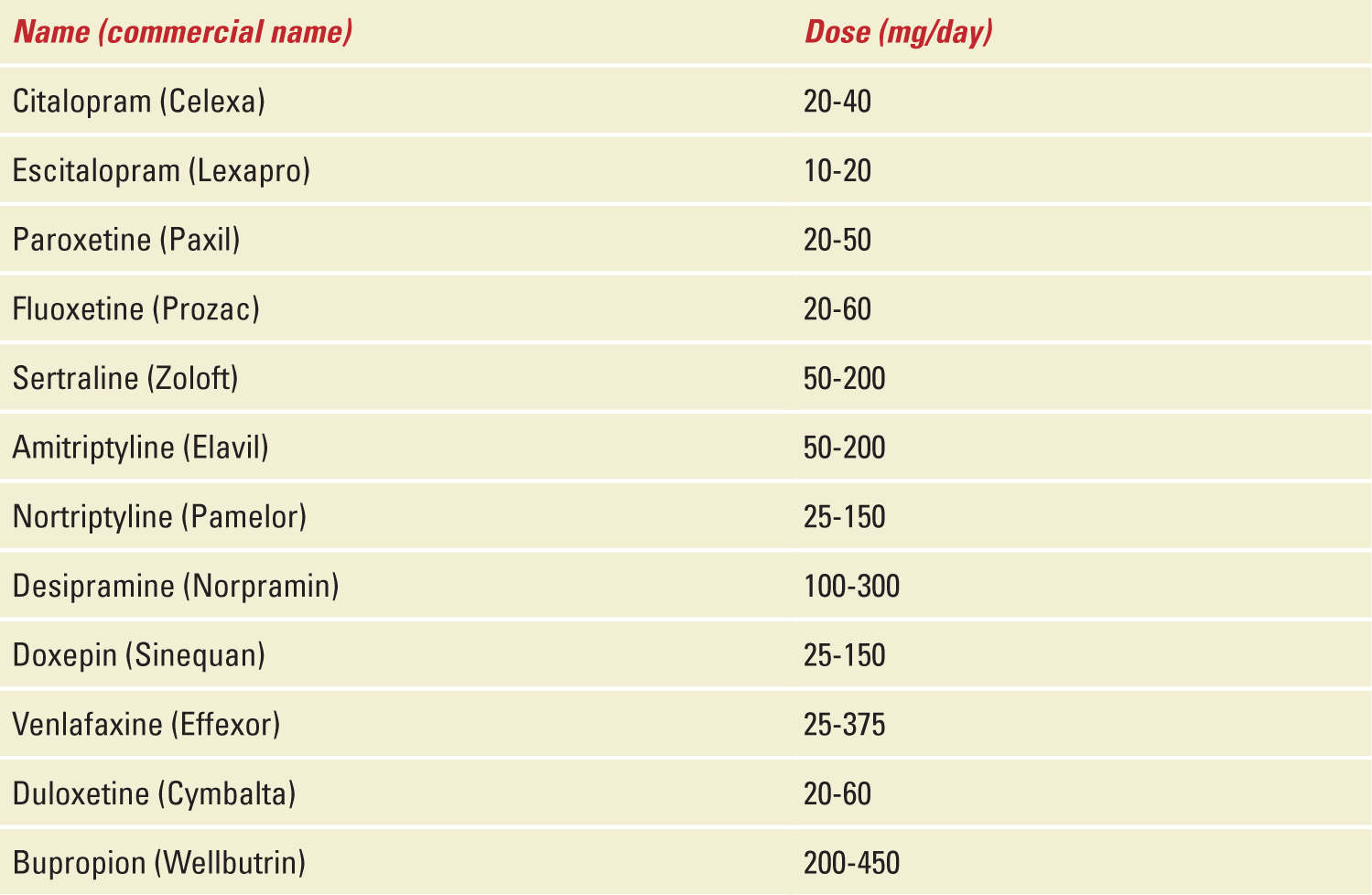

Most of the antidepressants used in pregnancy are FDA category C, which means that animal studies indicate an adverse effect on the fetus, but because there are no adequate, well-controlled human studies, the drug can be used during pregnancy if it is indicated (in other words, there is no good data for humans). Paroxetine and tricyclic antidepressants are category D, indicating that adequate, well-controlled human studies show risk to the fetus, but use of the drug in pregnant women may be acceptable despite the risk. A recent survey shows that antidepressant drug use during pregnancy increased from 2% in 1996 to 7.6% in 2004-2005.27 Common names with therapeutic doses of medications used are given in Table 24-1.

TABLE 24-1 | Drugs Commonly Used to Treat Depression During Pregnancy |

TRICYCLIC ANTIDEPRESSANTS (TCAs)—These common category D drugs include desipramine, nortriptyline, imipramine, amitriptyline, and clomipramine. There is no significant risk of congenital anomalies associated with TCAs. Reports of increased risk for small-for-gestational-age infants are mixed. Increased risk of transient neonatal withdrawal, which includes jitteriness, irritability, and convulsions, has been reported. Anticholinergic side effects in mothers, such as functional bowel obstruction and urinary retention, may occur but resolve within a few days.

Desipramine and nortriptyline are preferred due to fewer sedative, gastrointestinal, cardiac, and hypotensive side effects in the fetus. If a woman has insomnia, imipramine or amitriptyline may be prescribed in small doses (10-20 mg) for nightly use.

BUPROPION (WELBUTRIN)—The safety of bupropion has been studied for smoking cessation and depression during pregnancy, and the limited data show no adverse fetal or neonatal outcomes. It is, however, a category C drug. The MarketScan database (insurance claims data) showed exposure to bupropion during the second trimester correlated with increased risk of ADHD in children. Common maternal side effects are tachycardia, headache, insomnia, dizziness, xerostomia, weight loss, nausea, pharyngitis, and seizures. Less commonly seen side effects are agitation, arrhythmia, rash, constipation, and vaginal bleeding. This medication is contraindicated for individuals with eating or seizure disorders. Currently, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG; 2010) is of the opinion that there is insufficient information related to its use in pregnancy.

SELECTIVE SEROTONIN RE-UPTAKE INHIBITORS (SSRIS)—These drugs are divided into two classes: the SSRIs that include fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), and fluvoxamine (Luvox), as well as the selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which include venlafaxine (Effexor), desvenlafaxine, duloxetine (Cymbalta), and milnacipran.

These drugs act by blocking serotonin transporter (5HTT), which increases extracellular serotonin. Serotonin crosses the placenta and the blood brain barrier and can alter fetal serotonin levels. Serotonin plays a key role in the early developmental period. There is no consensus on SSRI use, as some studies are reassuring as far as neonatal outcome goes while others showed increased risk to fetuses and neonates.28–30 SSRI use has been linked to an increased risk for spontaneous miscarriage, postnatal adaptation syndrome, congenital heart defects, and neonatal persistent pulmonary hypertension (especially with use late in pregnancy).31,32 The National Birth Defects Prevention Study showed a twofold to fivefold increased risk of anencephaly, craniosynostosis, and omphalocele in infants of mothers exposed to SSRIs 1 month before pregnancy and/or in the first 3 months of pregnancy.33 A dose-dependent increased risk of cardiac defects (right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, atrial, and ventricular septal defect) with Paroxetine (category D) use in early pregnancy is the only report supported by recent reviews.34,35 Despite such associations, most of the available literature has found that SSRI’s are (if at all) weak teratogens and the risk of congenital anomalies associated with their use during pregnancy is less or equal to 1%.

Postnatal adaptation syndrome (PNAS) consists of a combination of symptoms in neonates including respiratory distress, feeding difficulty, jitteriness, thermal instability, sleeping problems, tremors, shivering, restlessness, convulsions, jaundice, rigidity, and hypoglycemia. The severity of PNAS is dose dependent.32 This withdrawal syndrome may occur in up to 30% of exposed neonates and is usually self-limited.

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) in infants exposed to SSRIs after 20 weeks of gestation may be increased by sixfold compared with controls.36 The latter association comes mainly from observational data and as such direct causality cannot be established. If in fact a correlation exists, the risk may be as low as 1%. No increased risk of autism among infants born to women treated with SSRIs for depression during pregnancy has been noted.37

Sertraline is often suggested as the first choice because of its low serum levels in breastfed infants. Fluoxetine has a long half-life and a higher rate of transfer through breast milk, which predisposes it to accumulation in the neonate.

SNRIs, such as venlafaxine and duloxetine, have limited data for use in pregnancy. However, no teratogenic effects have been seen with incidental use during pregnancy.

Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam and lorazepam, may be used in combination with SSRIs for treatment of depression with anxiety. These medications may be gradually tapered off once the antidepressant takes effect. Use should be restricted to less than 2 weeks, as prolonged use increases the risk of addiction and neonatal complications.

Treatment with SSRI does not guarantee remission of depression. Regardless of treatment, 16% of women may develop a major depressive episode during pregnancy.38 Because of changes in pharmacokinetics of SSRIs in pregnancy, dosing may need to be changed to achieve optimal therapy. After a recent review of SSRIs in pregnancy, Hanley et al concluded that first-line treatment with nonpharmacotherapy or psychotherapy should be considered during pregnancy.31

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Women often seek treatment other than standard medications during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. In the United Kingdom, over one-fourth of women reported using complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy.3 These alternatives include omega-3 fatty acids, folate, S-adenosyl-methionine, St. John’s wort, bright light therapy, exercise, massage, and acupuncture.

PSYCHOTHERAPY—In psychotherapy, also known as “talk therapy,” a therapist will work with patients to identify problems and modify their behavior to help relieve symptoms of depression. This therapy can be done as a “one-on-one” therapy session or in group therapy sessions where the therapist works with several people with similar conditions. Family and couples therapy are also options.

OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS—Omega-3 fatty acids include eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), essential fatty acids with theoretical health benefits for obstetric outcome and newborn development. To optimize pregnancy outcome, consensus guidelines recommend daily consumption of 200 mg of DHA. The Omega-3 fatty acids Subcommittee, assembled by the American Psychiatric Association, recommends that patients with mood disorder should consume 1 g EPA plus DHA daily.39

FOLATE—This supplement functions as a coenzyme in single-carbon transfers for the synthesis of nucleic acids and amino acid metabolism. Low folate levels have been associated with poor response to treatment with antidepressants in patients of major depressive disorder.40

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree