33 Dental and Oral Disorders

Normal Growth and Development

Normal Growth and Development

Anatomy of the Mouth

The Teeth

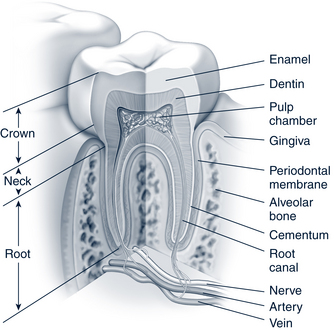

Anatomy of a Tooth

Primary and permanent teeth have similar anatomy, differing primarily in the size and external shape of each tooth. Figure 33-1 shows a cross section of the typical tooth including the crown (white part), neck, and root (encased in bone).

Pattern of Tooth Eruption

The permanent teeth begin erupting as children reach school age (about 6 years old), and the jaws grow. The eruption of permanent dentition begins with eruption of the mandibular central incisors and ends with the eruption of the maxillary third molars. The primary teeth are shed as the permanent ones erupt. The permanent molars erupt behind the primary molars. The shedding and replacement of the primary molars by permanent premolars is usually complete around the fifth grade or by 12 years of age. This period, when both primary and permanent teeth are present, is called transitional dentition. The total period of eruption of permanent teeth (except for the third molars) spans about 6 years in most children.

In general, the variability in eruption times for the permanent dentition is much greater than the variability observed in the primary dentition, with standard deviation of 8 to 18 months (about five times greater than in the primary dentition). The sequence of permanent tooth eruption is almost identical for both sexes. However, all teeth erupt earlier in girls than in boys. The gender difference in eruption times averages approximately 6 months. The tooth eruption pattern for both the primary and permanent dentitions is listed in Table 33-1.

TABLE 33-1 Calcification, Crown Completion, and Eruption

| Tooth | Age of Eruption |

|---|---|

| Primary Dentition | |

| Maxillary | |

| Central incisor | 7½ months |

| Lateral incisor | 8 months |

| Canine | 16-20 months |

| First molar | 12-16 months |

| Second molar | 20-30 months |

| Mandibular | |

| Central incisor | 6½ months |

| Lateral incisor | 7 months |

| Canine | 16-20 months |

| First molar | 12-16 months |

| Second molar | 20-30 months |

| Permanent Dentition | |

| Maxillary | |

| Central incisor | 7-8 years |

| Lateral incisor | 8-9 years |

| Canine | 11-12 years |

| First premolar | 10-11 years |

| Second premolar | 10-12 years |

| First molar | 6-7 years |

| Second molar | 12-13 years |

| Third molar | 17-21 years |

| Mandibular | |

| Central incisor | 6-7 years |

| Lateral incisor | 7-8 years |

| Canine | 9-10 years |

| First premolar | 10-12 years |

| Second premolar | 11-12 years |

| First molar | 6-7 years |

| Second molar | 11-13 years |

| Third molar | 17-21 years |

Adapted from Logan WHG, Kronfeld R: Development of the human jaws and surrounding structures from birth to age fifteen years, J Am Dent Assoc 20:379, 1993.

Managing Teething

A great number of folk remedies are used, especially in communities without good access to medical care (Smitherman et al, 2005). Rubbing whiskey on the gums or tying a penny on a string around the child’s neck (creates a potential risk of strangulation) are discouraged, as is using a honey-coated pacifier that might cause tooth decay or introduce botulism. At least one case of methemoglobinemia has been reported in a 6-year-old after the use of Baby Orajel for a toothache (had symptoms of cyanosis, vomiting, lethargy, and tachycardia) (Chung et al, 2010). Overuse of topical salicylates can cause burns.

The Oral Examination

The Oral Examination

Aberrations in Primary Tooth Eruption

Aberrations in Primary Tooth Eruption

Delayed tooth eruption

Delayed tooth eruption can result from either systemic or local factors. These include prematurity, low birthweight, genetic syndromes (e.g., Down and Turner syndromes), a diet low in protein, children born to mothers with severe goiter (iodine deficiency), hereditary gingival fibromatosis, and adjacent supernumeraries or dental tissue tumors (odontomes) (Crawford and Aldred, 2005; Hayes and Thornton, 2007). In general, children with chronic diseases who show delay in both physical and dental development experience delayed but otherwise normal tooth eruption. Parents may need reassurance if there is some delay. Once the child is old enough to tolerate dental x-rays, no earlier than 4 years old and often later, diagnostic films can be taken to provide a better assessment of the developing dentition.

Other Gum Events

Preeruption Cysts

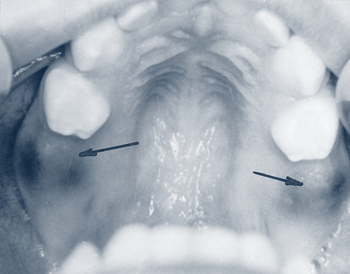

When a tooth starts erupting through the gingival tissue, a blood-filled cyst may precede it. Alarmed parents may report a purple, reddish, black, or blue bump or bruise in their child’s mouth. If the enlargement is on the alveolar ridge, reassurance is all that is required. The symptom will resolve as the tooth erupts (Fig. 33-2).

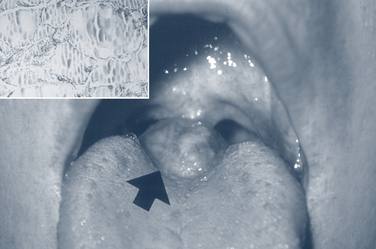

Congenital Epulis

Congenital epulis is a fibrous, pedunculated, soft-tissue enlargement that occurs on the maxillary alveolar ridge at birth (Fig. 33-3). This condition is more common in female babies. It typically regresses with time, but large lesions should be excised.

Bohn Nodules

Bohn nodules are present at birth and appear as firm nonpainful nodules on the buccal surface of the alveolar ridge (Fig. 33-4). They are remnants of dental lamina connecting the developing tooth bud to the epithelium of the oral cavity. No treatment is required because they will resolve spontaneously. If they appear in the midline of the palate, they are referred to as Epstein pearls.

Professional Dental Care

Professional Dental Care

Fear of the Dentist

Early and consistent primary prevention is the best way to avoid the development of fear and avoidance (Weinstein and Milgrom, 2006). Allowing tooth decay to go untreated until a child is school age results in extensive restorative intervention—a traumatic experience for any child. Dental restorative care is the only area of medicine in which children are expected to endure extensive surgery while they are awake. Hospitalizing children and performing reparative services under general anesthesia is a scarce, expensive, and risky option. Moreover, the majority of children experience recurrence of disease within 6 months because the surgical treatment does not address the underlying problem.

Dental Health Education

Dental Health Education

A good source of reference material on the Internet is www.medlineplus.gov, the consumer side of PubMed from the National Library of Medicine. Access is free, and materials are often in multiple languages. The site includes brochures that can be freely downloaded and copied.

Reducing Disparities Through Preventive Intervention and management

Weinstein and colleagues (2004) have shown that parents of young children are willing and able to change home preventive oral health practices. Using an intervention based on the transtheoretical “stages of change” model of Prochaska and Norcross, individuals overcome self-identified barriers to change, setting goals that are attainable and of personal value (Weinstein and Milgrom, 2006; Weinstein et al, 2004) (see Chapter 9 for discussion of this model).

Beil and Rozier’s study (2010) evaluated whether a recommendation by a PCP to see a dentist resulted in more dental checkups in children. They found that children 2 to 5 years who received such a recommendation were more likely to have a dental examination, whereas children from 6 to 11 years of age showed no increase. This supports the efficacy of the recommendation that primary care providers refer children to a “dental home” at an early age.

Bacterial Diseases of the Mouth

Bacterial Diseases of the Mouth

Tooth Decay (Cavities, Dental Caries)

Description and Epidemiology

In infants the carbohydrates may be present in the form of prolonged exposure to formula or breast milk, especially if the infant is allowed to sleep with the nipple in his or her mouth (Azevedo et al, 2005; van Palenstein Helderman et al, 2006). Before and after weaning, carbohydrates may also come from milk sweetened with honey or sugar or from juices in baby bottles or training cups, especially when given at bedtime, naptime, or when a child is allowed to take swigs of the fluid throughout the day. In older children, the source of the carbohydrates may be Tang, Kool-Aid, sports drinks, and/or soda. This frequent carbohydrate exposure keeps the pH of mouth fluid near the tooth surface below 5 and results in an environment conducive to demineralization. The neutralization process does not have enough time to increase the mouth pH to a level that would allow remineralization. In patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation to the head and neck and in patients who are immunocompromised, normal salivary flow and salivary buffering of acids is disrupted. Cavities result. Box 33-1 provides a list of risk factors associated with dental caries in children.

BOX 33-1 Factors That Increase a Child’s Risk for Developing Dental Caries

Health and Personal History

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD): Reference manual 2009-2010: policy on use of a caries-risk assessment tool (CAT) for infants, children, and adolescents, Pediatr Dent 31(special issue):29-33, 2009a.

Clinical Findings

Clinical findings can include the following:

• Early caries lesions. These appear as horizontal white or brown lines or spots along the upper central gumline or gingival margin, more commonly in populations using baby bottles because the cavity-causing fluids pool in these areas of the mouth (breastfed babies are not necessarily excluded from such lesions). In cultures where bottle use, especially at night or naptime, is less common the damage may occur in back teeth first as a function of other dietary patterns. When white lesions occur, the dentin is initially damaged. Then, as the lesion progresses, the hard enamel breaks, and a clinical cavity is evident (see Color Plate). Baby teeth are important for chewing food, serve an aesthetic function, and hold space in the mouth so that the permanent teeth can erupt properly. Therefore, it is critical to prevent cavities and intervene early in any decay.

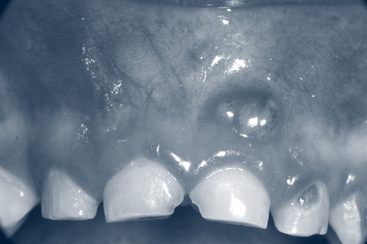

• Advanced tooth decay. This appears as cavitations in the teeth. Nearly all cavities in permanent teeth in children in the U.S. begin on the biting surface of the molars. The initial lesion appears as a pinhole surrounded by a white, opaque halo. As the lesion enlarges greater damage to the enamel becomes apparent. Lesions typically appear about 1 year after the eruption of the tooth and frequently begin while the tooth is still erupting. A gumboil may form if the tooth becomes abscessed (Fig. 33-5).

• Sensitivity. Cavities can be hot, cold, or sweet sensitive.

• Localized pain. Lesions that progress can begin to hurt all the time, disrupting normal activity, sleeping, and eating.

• Inflammation and abscesses. Bacterial invasion of the pulpal tissue in the tooth causes inflammation and necrosis. In severely decayed primary teeth, a gumboil or draining fistula will form on the gum tissue above the root end of the tooth. This also occurs in permanent teeth, but is a late stage (see Fig. 33-5).

• Methamphetamine use (“meth mouth”) can cause accelerated tooth decay on the facial surfaces of the teeth and between the teeth. In later stages the teeth are blackened, stained, and appear to be crumbling. There may be signs of severe grinding and dry mouth (Klasser and Epstein, 2005). See the discussion on the use of 12% chlorhexidine gluconate oral rinse for this condition.

• Cavities may spontaneously arrest. This is thought to occur, for example, when cavities are exposed to saliva high in fluoride or when the diet changes (such as after weaning). Arrested caries appear as open cavities that are black or dark brown. If the child has such open cavities, is asymptomatic, the teeth are primaries, and access to dental care is problematic, these teeth can be left alone and allowed to shed normally. Ideally, these children should receive dental care. The discoloration also may be the result of previous topical treatment by a dentist with diamine silver fluoride or silver nitrate that was used in an attempt to arrest and prevent carious lesions.

Management and Prevention Strategies in Primary Care

Fluoride Varnish

1. Dispense approximately 0.5 mL of varnish into a small well. Prepackaged individual-dose systems come with their own well that is filled with varnish.

2. Lightly dry the teeth with air or gauze to remove moisture.

3. While keeping the teeth isolated from further moisture contamination, paint the varnish onto the teeth with a brush or another type of applicator (Fig. 33-6). The varnish sets on contact with the slightly moist teeth.

A short training video on the technique for applying varnish is available from the National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center at www.mchoralhealth.org/highlights/flvarnish.html..

Fluoride Therapy

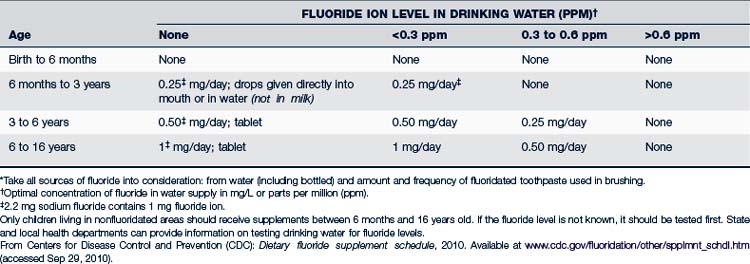

The most effective preventive measure against dental caries is optimizing the fluoride content of communal water supplies (a new proposal recommends the optimal level be reset to 0.7 ppm [USDHHS, 2011]). However, only about 50% of children in the U.S. drink fluoridated water. Children who consume fluoride-deficient water supplies and who are at risk for caries will benefit from dietary fluoride supplementation (CDC, 2010b).The fluoride level of public water supplies can usually be ascertained by calling the local health department. If the patient uses a private water supply, the fluoride level should be tested before prescribing fluoride supplements. To prevent potential overdoses, no prescription should be written for more than a total of 120 mg of fluoride. See Table 33-2 for adjusting the dose of fluoride supplements in relation to that found in the community water supply.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree