78 Demyelinating Diseases

Clinical Presentation and Differential Diagnosis

Clinically Isolated Syndrome

Optic Neuritis

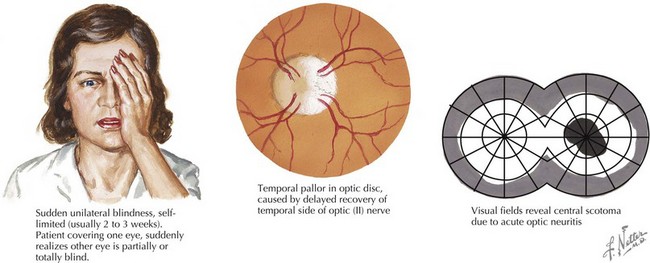

Optic neuritis is characterized by acute or subacute visual loss, altered color vision, periorbital pain that is exacerbated by eye movements, and visual field defects. The neuro-ophthalmologic examination may reveal a relative afferent pupillary defect (in unilateral cases) or optic disc edema (Figure 78-1). MRI of the orbits often reveals T2/FLAIR abnormality in the optic nerve or chiasm with or without enhancement using gadolinium. Visual recovery from idiopathic optic neuritis is excellent for most children, especially in the absence of alternate diagnoses such as NMO.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree